- Share

Estimating the Impact of Fast-Tracking Foreclosures in Ohio and Pennsylvania

All the signs in the housing market seem to be pointing the right way, except the amount of time loans are spending in the foreclosure process. Foreclosure fast-tracks for vacant homes in foreclosure may help reverse that trend.

The views authors express in Economic Commentary are theirs and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The series editor is Tasia Hane. This paper and its data are subject to revision; please visit clevelandfed.org for updates.

In recent months housing markets have shown real signs of life: home prices, home purchases, and housing starts are up, while foreclosure inventories, foreclosure starts, and loan delinquencies are down. But in states that handle foreclosure through the courts (rather than nonjudicial trustee’s sales), the lingering effects of the foreclosure crisis may be costing taxpayers money and dragging down the recovery. In those states, the amount of time loans are delinquent before they enter foreclosure and the amount of time loans spend in the foreclosure process are rising.

Anecdotally, many explanations have been offered as to why this is happening. Loan modification programs may explain some of the increase in duration, as lenders work with borrowers in an attempt to modify the loan while the borrowers are delinquent or in foreclosure instead of proceeding to judgment. State-specific requirements, such as the lender having to produce the original note and mortgage may delay or prevent some foreclosures on delinquent loans. Shrinking budgets may be making it difficult for the courts overseeing the cases or the sheriff’s offices overseeing the property auctions and deed transfers to process foreclosures in a timely way. Selective foreclosure, which avoids low-value properties, may also be a contributing factor, shifting the costs of those properties from the lender to communities and taxing districts.

These problems are intensified when a home that is in the judicial foreclosure process is vacant. States with judicial foreclosure have longer foreclosure timelines than nonjudicial states. When the home is vacant, the cost of the extended judicial foreclosure process has no corresponding benefit, generating deadweight losses.

Recently, some judicial foreclosure states have passed laws that attempt to “fast-track” foreclosures if the property has been abandoned by the homeowner, and others have begun considering similar fast-track laws. This Commentary explores the economic reasoning behind fast-tracking and estimates the size of the deadweight loss that could be eliminated by creating an effective foreclosure fast-track in Ohio and Pennsylvania, two states in the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland’s District.

The Judicial Foreclosure Process

Requiring that foreclosures be conducted through the courts is a policy decision that has passionate advocates on both sides of the issue. Those that do require it—judicial foreclosure states—have decided that certain safeguards are required before real property can be taken from an owner by a creditor because of a default on a secured loan or by a taxing authority for failure to pay property taxes. In these states creditors and taxing authorities must proceed through the courts, which make sure they have the right to foreclose and the borrower has no legal defenses to foreclosure.

Legislatures have decided that protecting the rights of property owners is worth the higher cost of judicial foreclosure relative to nonjudicial foreclosure. These costs may change depending on whether homes stay occupied or are vacated by the owners during the foreclosure process. When a home in foreclosure remains occupied, the costs may only include the lost value of the creditor or taxing authority’s capital investment in the property (which does not earn a return during the foreclosure process), the litigation costs of all parties to the foreclosure, and the court’s time. But when a residential property in foreclosure is vacant, this calculation may change.

When the foreclosure sits vacant, there are additional costs to the creditor or taxing authority due to the accelerated depreciation of unoccupied homes, which are less well maintained and more likely to be vandalized or, in some cases, stripped of metal to sell for scrap. There are additional costs to the community when unoccupied homes create health and safety hazards and cause surrounding homes to lose value. In states that allow deficiency judgments such as Ohio and Pennsylvania, there are potentially further costs to the vacated homeowners, who will be liable for the difference between the price the creditor or taxing authority eventually receives for the home and the unpaid loan amount. Finally, any loss in property values will hurt municipalities or school districts funded in whole or in part by taxes on the value of real property.

Who bears these costs, in the end, depends on whether the foreclosure is completed. When the foreclosure is abandoned, costs are imposed on the community and taxing districts. The abandoned property is not easily rehabilitated due to the lender’s lien on the property. When abandoned properties are taken through foreclosure and sold, these costs are born primarily by the lender through rehabilitation costs or lower sales prices.

Most importantly, there is no obvious beneficiary of these costs. Communities and taxing districts face the externalities associated with vacant property: lower surrounding home values, increased crime, and reduced property tax collections. Homeowners who leave properties vacant are essentially resigned to the fact that they cannot dispute the right of the creditor or taxing authority to take the home through the foreclosure process, and as such gain no benefit from its use. Lenders receive no benefit from the judicial foreclosure process above the benefits they would receive through a nonjudicial process.

These deadweight losses—costs without corresponding benefits—are what legislatures in judicial foreclosure states have attempted to address by creating foreclosure fast-tracks. At least five states have created foreclosure fast-tracks for private mortgage foreclosure on abandoned property since 2010.1 Ohio created a private mortgage foreclosure fast-track for tax-foreclosure in 2006,2 and the Ohio legislature is considering a pilot foreclosure fast-track for properties abandoned by the homeowner.3 But there has been no economic analysis to determine the potential impact of a well-designed foreclosure fast-track.

Assuming a Close-to-Ideal Foreclosure Fast-Track

We estimate the potential for savings that an efficient and effective foreclosure fast-track could provide in Ohio and Pennsylvania. The savings would come from shortening the amount of time that vacant properties spend in foreclosure and eliminating the deadweight losses lenders suffer. To estimate these savings, we need to know three things: how many foreclosures might be affected (the number of homes in foreclosure that sit vacant), the daily deadweight losses associated with these homes, and time that could be shaved by fast-tracking.

Unfortunately, there is no single database that has all this information, so constructing our estimate is a multi-step process. We start by making several assumptions. We assume that an ideal fast-track for private mortgage foreclosure would only apply to homes in foreclosure that owners have vacated, it would be used on 100 percent of those properties, and it would cut the total foreclosure time—specifically, from the time the foreclosure is filed with the court to the point where the lender takes ownership of the property—down to two months.

The validity of these assumptions depends entirely on how the law is written. Typically, foreclosure fast-track laws require more than simple vacancy in order to qualify for the fast-track, which protects against the fast-track being misused but may prevent all vacant foreclosures from being eligible for fast-tracking. In some cases, qualification is based on criteria that would correlate with a vacated home (shut-off utilities and housing code violations, for example), so generally there should be a high correlation between vacancy and fast-track qualification. Additionally, once a foreclosure judgment is issued, the fast-track would have to transfer the property to the lender directly, or an expedited foreclosure auction and deed transfer process would be required.

A 100 percent utilization rate of a foreclosure fast-track also depends on how efficiently the process is designed: the faster and easier it is to use, the more it will be used. It is worth noting that a common anecdotal complaint by creditors’ counsel is that recently-passed foreclosure fast-tracks are difficult to use.

Another practice that may prevent 100 percent utilization is strategic foreclosure. Strategic foreclosure refers to foreclosures that are started but never completed or foreclosures that are never started because the lender determines that the home has little value. They usually occur when the home sits vacant and depreciates to the point that it would cost more to foreclose upon and maintain than could be recovered by selling the property. There is some empirical evidence suggesting that this has occurred in very weak markets.4 And anecdotally, local governments and communities have reported an increase in foreclosures that start but are never completed. A foreclosure fast-track does not completely address strategic foreclosure. It may lower the cost of foreclosure for lenders, but if the property has an extremely low net present value, lowering the cost of foreclosure may still not be enough to make completing the foreclosure worthwhile. A fast-track law could be constructed with features that ensure foreclosures that have started are completed, but the response to that might be to not initiate foreclosure on low-value properties, in which case the problem will persist.

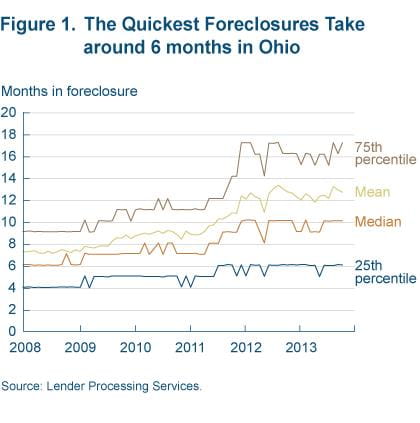

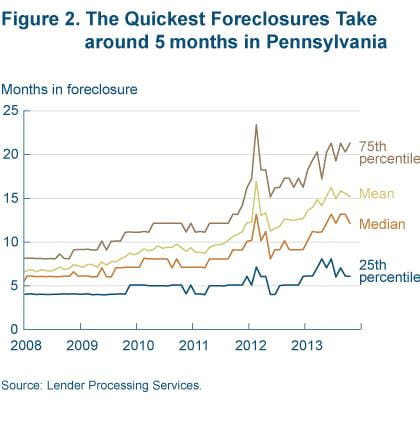

Finally, bringing the fastest foreclosures down to two months also seems possible. The quickest foreclosures in Ohio and Pennsylvania are completed typically in five to six months (figures 1 and 2). This is a measure of the time that loans spend in foreclosure before they enter the lender’s real estate owned portfolio or are sold. In the case of vacant foreclosures, a fast-track could move the process down to a single hearing, and if the homeowner does not respond to the foreclosure filing, the property could be directly transferred to the lender or move to an accelerated sale. This process would be similar to the fast-tracked property tax foreclosure framework currently used in Ohio.

Estimating the Number of Vacant Foreclosures

To determine the number of vacant homes in foreclosure in Ohio and Pennsylvania, we have to combine data from two different sources. Lender Processing Services (LPS) provides an estimate of the share of first-lien loans that are in foreclosure in each state. RealtyTrac provides an estimate of the share of homes in foreclosure that are vacant in each state. Combining the two estimates will give us an idea of how many foreclosures might be affected by fast-tracking. We also use LPS data to calculate the average duration of the foreclosure process, which we need to estimate the amount of time that fast-tracking could save in the foreclosure process (average duration minus our two-month assumption).

RealtyTrac determines the share of vacant foreclosures by cross-referencing the addresses of properties in foreclosure with US postal data. Those foreclosed properties that have left forwarding addresses or have been designated as vacant by the postal service are considered vacant foreclosures by RealtyTrac. In Ohio, roughly 20 percent of homes are vacant while they are in foreclosure according to this estimate, while in Pennsylvania the ratio is closer to 16 percent (table 1).

Table 1. Around 20 Percent of Homes in Foreclosure Are Vacated by Owners in Ohio, 16 Percent in Pennsylvania

|

|

Vacated by the owner, percent | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | |

| Ohio | 21 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| Pennsylvania | 17 | 17 | 16 | 15 |

Source: RealtyTrac. This data can be purchased at http://data.realtytrac.com.

To calculate the average duration of the foreclosure process, we start by identifying all loans that exit the foreclosure process by entering into a creditor’s real estate owned portfolio or by being sold by the creditor. Then we count how many consecutive months those loans were marked as “in foreclosure” by the creditor.

One challenge of our approach is that RealtyTrac counts the number of homes in foreclosure, while LPS counts the number of first-lien loans in foreclosure. These sets will not correlate perfectly for a few reasons. First, they count foreclosure slightly differently—LPS relies on monthly self-reporting from servicers, while RealtyTrac counts a home in foreclosure from the day the notice of default is issued through the day the notice of sale is issued. The RealtyTrac set also focuses on homes, so it may include foreclosures that do not have an associated mortgage loan (property tax foreclosures, for example). Despite these minor differences, we feel the sets are similar enough to export the rate of vacant foreclosures from one to the other.

Estimating the Impact

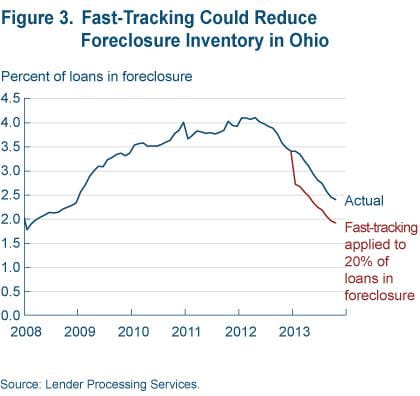

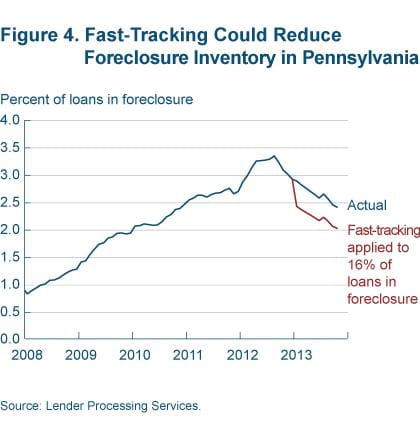

Using the vacant foreclosure rate of 20 percent for Ohio and 16 percent for Pennsylvania, we estimate that both states would likely experience a substantial reduction in foreclosure inventories if they had had a fast-track in place at the end of 2012. If Ohio had passed a foreclosure fast-track, the foreclosure inventory in Ohio would be about 0.5 percentage points lower—less than 2 percent instead of just under 2.5 percent (figure 3). Pennsylvania would see similar results (figure 4).

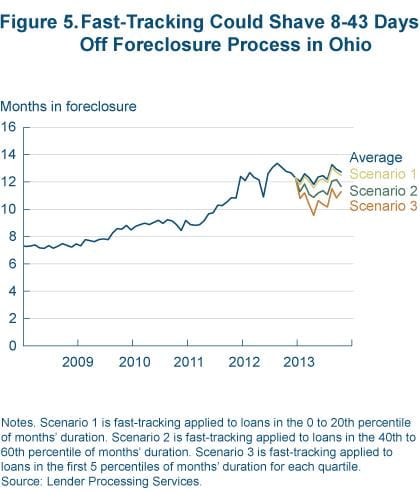

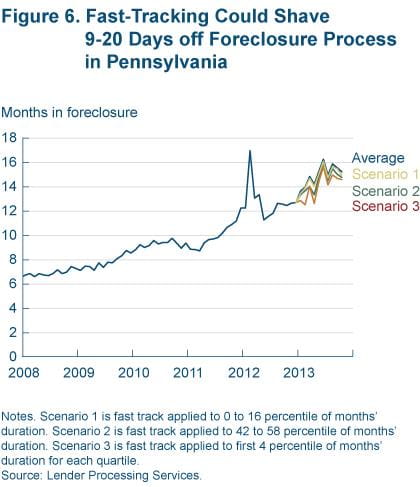

Calculating the impact a fast-track would have on the amount of time loans spend in foreclosure in each state is not as straightforward. We do not know which loans would be eligible for a fast-track, so we created three scenarios.

- Scenario 1. We applied the fast-track to the loans in each state that are already moving through the process most rapidly.

- Scenario 2. We applied the fast-track to the loans closest to the average durations without the fast-track (40th to 60th percentile in Ohio and 42nd to 58th percentile in Pennsylvania).

- Scenario 3. We applied the fast-track to the fastest loans in each quartile or the first five percentiles of each quartile (0-5, 26-30, 50-55, 76-80) in Ohio and the first four percentiles in Pennsylvania (0-4, 26-29, 50-54, 76-79).

In Ohio these scenarios shave between 8 and 43 days off of the average duration (figure 5). In Pennsylvania durations are lower overall, and the scenarios create a narrower range of 9 to 20 days shaved off of the average foreclosure duration (figure 6).

Notes: Scenario 1 is fast track applied to 0 to 16 percentile of months' duration. Scenario 2 is fast track applied to 42 to 58 percentile of months' duration. Scenario 3 is fast track applied to first 4 percentile of months' duration for each quartile.

Source:Lender Processing Services

It is worth noting that this simple method may underestimate the impact a fast-track would have on durations, because it assumes that all noneligible loans would continue to move through the process at their current pace. That seems unlikely, as freeing up judicial resources via the fast-track should help reduce the time even non-fast-tracked loans spend in foreclosure.

Finally, we attempt to put a dollar figure on the deadweight loss eliminated by the use of a foreclosure fast-track. This is by far the most challenging part of this analysis because these costs cannot be observed directly in the data we have.

The cost to homeowners, communities, and taxing authorities cannot be reasonably estimated because we do not observe them directly or indirectly in either of the data sets used in this analysis. Other research suggests that the savings to these entities would be substantial. Whitaker and Fitzpatrick (2013)5 find that in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, each vacant property lowers the sale prices of surrounding homes by $1,300 to $2,300. If a fast-track was able to reduce the amount of time homes spend vacant by speeding them through the foreclosure process and eventually to new owners, they would no longer be vacancies that reduce the sales prices of surrounding homes.

Similarly, if a fast-track could prevent vacant foreclosures from depreciating to the point of abandonment in the foreclosure process, those abandoned homes would not lower the sale price of surrounding properties by $700 to $6,000. But exact estimates would require different data to allow us to view the spatial distribution of vacant foreclosures in Ohio and Pennsylvania, the strength of the housing submarkets they are in, and the housing density in those markets.

Additionally, Cui (2010)6 estimates that spells of residential vacancy in Pittsburgh exceeding six months result in significantly higher rates of violent crime in their immediate vicinity. It follows that reducing the time homes spend vacant in the foreclosure process to less than six months could reduce the instance of violent crime in the surrounding area, but no dollar figure can easily be placed on this effect, and it cannot be measured with precision.

We do not directly observe the costs to creditors, but they can be estimated by looking at creditors’ daily carrying costs for the property they own. These carrying costs are calculated for creditors’ REO portfolios and include ongoing maintenance, taxes, repairs, and code-violation citations for the residential properties they own. They include some fixed costs that are averaged over the few months lenders typically own properties after foreclosure. While not a direct observation, they likely reflect the extra attention creditors must pay to vacant foreclosures to maintain them, or the depreciation of vacant properties (resulting in lower sale prices) that are unmaintained. Nationally, creditors’ carrying costs are estimated to be between $25-$100 a day.7 Conversations with loan servicers working in Ohio and Pennsylvania suggest costs in those areas are closer to $50-$100 a day.

Taking the average of the daily carrying-cost range for Ohio and Pennsylvania, multiplying it by the average time saved under each scenario and the number of loans in foreclosure in each state brings us to an estimated annual savings for each state, had a foreclosure fast-track been in place at the end of 2012. In Ohio, the annual savings from a foreclosure fast-track is estimated to be between $24,000,000 and $129,000,000 (table 2). In Pennsylvania, the annual savings from a foreclosure fast-track is estimated to be between $24,000,000 and $54,000,000 (table 2). It is important to emphasize that this is an elimination of deadweight losses, rather than a shifting of costs. That is, these costs already exist and benefit no one.

Table 2. Fast-Tracking Could Have Saved Creditors $24 Million to $129 Million in 2013

| Days saved (A) |

Daily carrying costs, dollars (B) |

Number of loans in foreclosure (C) |

Total cost savings, dollars (AxBxC) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario | Ohio | |||

| 1 | 8 | 75 | 40,000 | 24,000,000 |

| 2 | 31 | 75 | 40,000 | 93,000,000 |

| 3 | 43 | 75 | 40,000 | 129,000,000 |

| Scenario | Pennsylvania | |||

| 1 | 9 | 75 | 36,000 | 24,300,000 |

| 2 | 14 | 75 | 36,000 | 37,800,000 |

| 3 | 20 | 75 | 36,000 | 54,000,000 |

Source: RealtyTrac; Lender Processing Services; authors’ calculations.

These savings to creditors raise the question of why creditors do not simply fund adequate staffing in the proper local government offices and hire additional attorneys of their own to move vacant homes through the foreclosure process faster. There are two reasons why this does not happen, one economic and one legal.

Economically, these savings are spread over a large number of lenders prosecuting a large number of foreclosures in a large number of courts throughout the states of Ohio and Pennsylvania. Determining where lenders need additional attorneys, and which courts require additional staff, would be an expensive proposition. It creates a classic collective-action problem, where no one lender would save enough to return their investment. Even in the absence of this collective-action problem, there are legal barriers (statutorily prescribed notice and hearing requirements and accompanying periods laid out by rules of civil procedure) that would prevent homes from being accelerated through the foreclosure process. Even if it were feasible for creditors to fund adequate staffing in the proper local government offices, it would not be a substitute for an act of the legislature creating a usable foreclosure fast-track for vacant foreclosures.

Conclusion

All the signs in the housing market seem to be pointing the right way, except the amount of time loans are spending in the foreclosure process. Foreclosure fast-tracks for vacant homes in foreclosure may help reverse that trend.

The data suggest that the foreclosure rate could be substantially lowered and tens of millions of dollars of annual deadweight losses could be eliminated in Ohio and Pennsylvania annually by creating efficient, effective foreclosure fast-tracks for vacant properties. Crafting legislation that adequately balances the interests of creditors and homeowners while meaningfully fast-tracking foreclosures is no simple task, and would likely require the input of creditors, communities, foreclosure attorneys, and the judiciary.

Footnotes

- See “Policy Considerations for Improving Ohio’s Housing Markets,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Staff Report, 2013. Return to 1

- Ohio Revised Code §323.65 et seq. Return to 2

- Ohio House Bill No. 223, 130th General Assembly, 2013-2014. Return to 3

- Stephan Whitaker and Thomas J Fitzpatrick IV, 2013. “Deconstructing Distressed-Property Spillovers: The Effects of Vacant, Tax-Delinquent, and Foreclosed Properties in Housing Submarkets, Journal of Housing Economics, 22(2): 79-91. Return to 4

- See footnote 4. Return to 5

- Lin Cui, 2010. “Foreclosure, Vacancy, and Crime,” University of Pittsburgh Department of Economics, working paper. Return to 6

- Andrew Jakabovics, 2012. “What Sells When: Analyzing Price and Time Patterns for Single-Family Homes to Identify Best Practices for Aggregating REO Properties for Bulk Sales,” Enterprise Community Partners, working paper. Return to 7

Suggested Citation

Fee, Kyle D., and Thomas J. Fitzpatrick IV. 2014. “Estimating the Impact of Fast-Tracking Foreclosures in Ohio and Pennsylvania.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary 2014-03. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-ec-201403

This work by Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International