Why Wasn’t there a Nonbank Mortgage Servicer Liquidity Crisis?

In March 2020, in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, many were concerned about the liquidity of nonbank mortgage servicers. As it turned out, the vast majority of these servicers did not face a liquidity crisis. In this Commentary I detail the reasons why, including lower than expected take up rates of forbearance, the role played by mortgage origination income, and the actions taken by the government-sponsored enterprises, Ginnie Mae, and housing agencies.

Nonbank mortgage companies (NBMCs) are companies that originate and service mortgages. They do not take deposits or have banking charters, but, instead, fund mortgage originations by borrowing from banks. Concerns about the risk NBMCs pose to financial stability have been raised in recent years, and at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, those concerns grew.

In the end, NBMCs had few liquidity problems, they created no financial instability, and they have been relatively profitable during the pandemic. In this Commentary I explain the concerns about NBMCs, why these concerns were greatest for the servicers of Ginnie Mae securities, and why a broad-based liquidity crisis among these companies did not materialize during the COVID-19 pandemic. This explanation has implications for policymakers as they consider the ability of NBMCs to weather future shocks.

Financial Stability Concerns with NBMCs

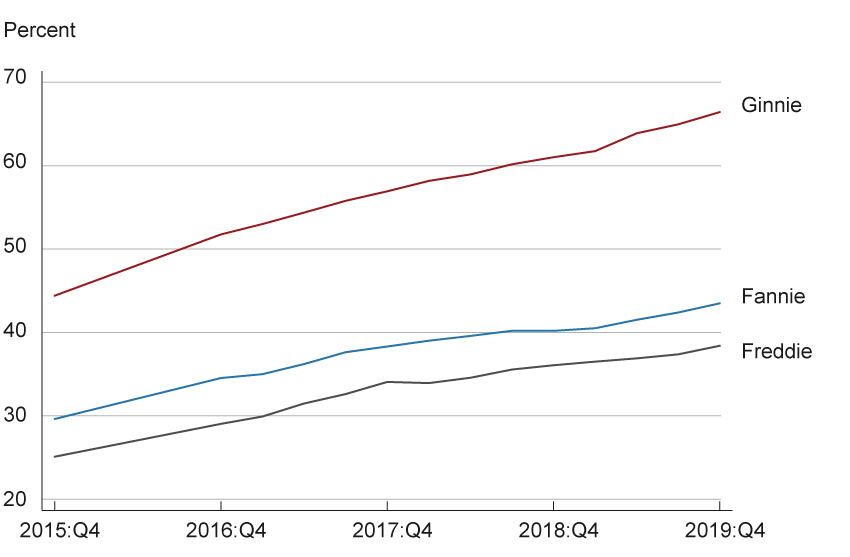

The NBMCs are not new members of the mortgage market, but their role has changed over time. During the 2000s housing boom, they were prominent in the market for loans sold into private-label securities, and during the foreclosure crisis, they specialized in servicing delinquent loans. Since the Great Recession, they have become larger players in mortgages originated for sale to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs)), and especially for loans in Ginnie Mae securities, for which NBMCs have serviced over 65 percent of the loans as of the end of 2019 (see figure 1).1

Figure 1. Share of Agency Servicing Performed by Nonbanks

Source: Inside Mortgage Finance.

Concerns about the risks NBMCs pose to financial stability are twofold. The first relates to the NBMCs’ role in funding originations, funding which they do by using warehouse lines of credit from banks. In the event of a large macroeconomic event or apprehensions about a specific NBMC, the concern is that banks could potentially shut off these lines of credit, an event which would limit the ability of NBMCs to originate mortgages and potentially disrupt their ability to service mortgages if their viability were threatened.2

The second has to do with the NBMCs’ role in servicing mortgages. A mortgage servicer collects borrowers’ monthly mortgage payments and keeps track of whether borrowers have made these payments on time. If the mortgage in question is part of a mortgage-backed security (MBS),3 which is generally the case for mortgages serviced by NBMCs, the servicer forwards the payment (minus a fee) to the investors or issuers of that security. The fee is a percent of the unpaid mortgage balance. For a performing loan, this is a profitable arrangement. However, servicing becomes more complicated in the event the borrower defaults. The servicer must often continue to forward some or all of the mortgage payment to the investors in the MBS; continue making insurance and tax payments (and occasionally homeowners association fees) on behalf of the borrower regardless of whether the borrower is making payments or not; and continue paying fees to relevant government agencies. During a crisis, widespread defaults could threaten the viability of a given NBMC because there can be a substantial amount of time during which the NBMC must forward these payments before the NBMC gets reimbursed.

It was this latter point that was at the forefront of the concerns raised during the debate over the CARES Act. The CARES Act included a provision that allowed borrowers of any government insured loan to receive up to 12 months’ forbearance on their loans with little to no documentation or proof of hardship. Mortgage forbearance gives the borrower temporary relief from the entire mortgage payment, including taxes and insurance payments. The CARES Act also forbade charging interest on forborne balances, meaning that forbearance was effectively an interest-free loan to the borrower. The concern was that so many people would request forbearance that NBMCs would face liquidity constraints as they continued to advance payments on behalf of borrowers who had requested forbearance.

The NBMCs advocated for the creation of a 13(3) facility, which would allow them to borrow from the Federal Reserve, if necessary, to cover these payments. Normally, NBMCs do not have access to the Federal Reserve’s discount window because they are not members of the Federal Reserve. Other industry watchers and participants also thought a facility was necessary. They argued, first, that liquidity constraints among NBMCs might affect the origination market, and second, in the event of a mortgage company failure, the need to transfer the failed company’s servicing portfolio could cause confusion and chaos for borrowers, especially those in the midst of loss mitigation negotiations.

The concern was taken seriously. On March 30, 2020, the US Department of the Treasury announced the formation of a task force to look into the question of servicer liquidity, but by the end of April, it was decided that no liquidity facility would be created. The reasons given were that GSEs, Ginnie Mae, and related agencies had adopted policies to mitigate immediate liquidity concerns and that nonbank mortgage servicers do not present a systemic risk to the financial system.

NBMCs, the Agencies, and Ginnie Mae

Concerns were always most heightened for servicers of Ginnie Mae loans,4 which are loans insured by various government agencies including the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), the Veterans Administration (VA), or the USDA Rural Development (RD) program and sold into MBS backed by Ginnie Mae.

One reason for the concerns is that borrowers of the loans packaged into the securities backed by Ginnie Mae are riskier on average than borrowers of GSE loans. Those concerned about the NBMCs expected forbearance rates to be substantially higher for these borrowers. In addition, servicers of loans in Ginnie Mae securities have more responsibilities than servicers of GSE loans largely because Ginnie Mae is more limited in its abilities to provide assistance. Ginnie Mae is a relatively small operation that acts only as a guarantor of Ginnie Mae securities. In contrast, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are large institutions that purchase loans from originators and issue securities themselves. They therefore take on the credit risk of the underlying mortgages, while issuers of Ginnie Mae securities rely on the FHA, VA, and RD for that insurance.

Because of their heft and responsibilities, Fannie and Freddie are able to extend aid to the firms servicing their loans. For example, they can incentivize servicers by paying a supplemental servicing fee, reimburse servicers for property tax and insurance advances, and also step in and directly forward payments to investors in lieu of their servicers. They also can—and generally do—have remittance schedules with their servicers that allow the servicers to advance only the actual principal paid by the borrower and not the interest. This means that during forbearance, servicers of GSE loans generally have to forward only the amount actually paid by the borrowers, not the amount owed by the borrowers.

Ginnie Mae can do none of these things. Instead, it is the insuring agency—the FHA, VA, or RD—that can change the servicing fee or reimburse servicers for advances. Only in the event of the insolvency of a servicer will Ginnie Mae step in to forward payments to investors in lieu of the servicer. Therefore, the servicers of Ginnie Mae loans, NBMCs included, are responsible for remitting full principal and interest payments to investors and making property tax and home insurance payments on the behalf of borrowers, forwarding mortgage insurance payments to the relevant agency (the FHA, VA, or RD), and forwarding a guarantee fee (a fee to pay Ginnie Mae for guaranteeing the security) to Ginnie Mae.

Why Was There No Broad-Based Liquidity Crisis among Nonbank Mortgage Servicers?

There are multiple reasons why the majority of nonbank servicers, even those of loans in Ginnie Mae securities, did not face a liquidity crisis. While I do not quantify the exact contribution of each reason, understanding the lack of a crisis has implications for policymakers when considering the future financial stability of NBMCs.

Forbearance Take-up Was Not As High As Some Anticipated

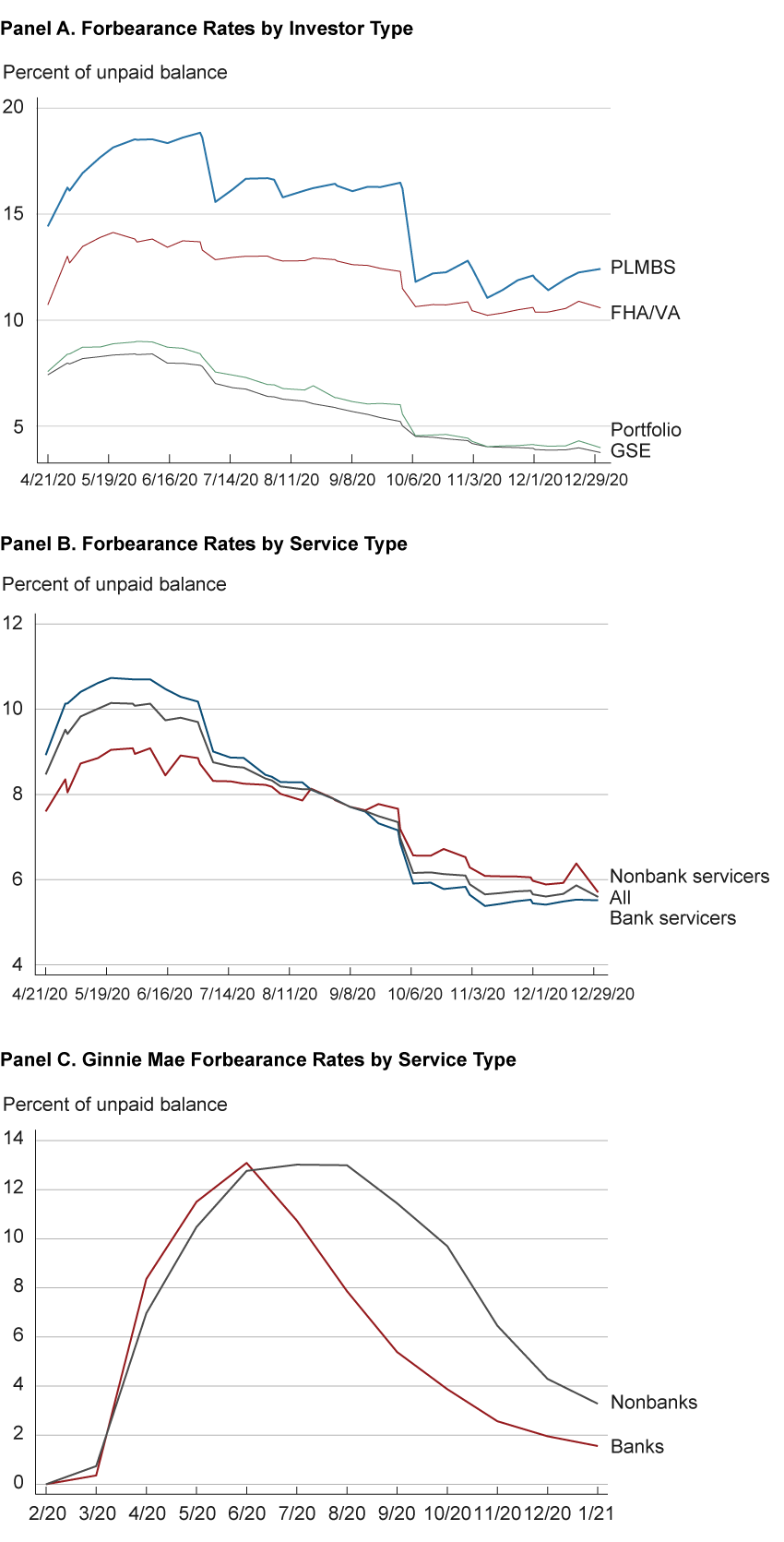

In the early days of the pandemic, estimates of the projected percent of borrowers that would request forbearance varied widely, ranging from the single digits (most notably from then FHFA director Mark Calabria) to as high as 25 percent (largely from members of the mortgage servicing industry).5 In the end, actual forbearance rates landed within that broad range, but closer to the low end. As can be seen in panel A of figure 2, forbearance rates for GSE loans remained in the single digits, and forbearance rates for Ginnie Mae loans and loans in private-label mortgage-backed securities (PLMBS) breached 10 percent and 15 percent, respectively. Despite the fact that nonbank servicers often originate and service loans made to riskier borrowers, initial overall forbearance rates were lower for loans serviced by NBMCs than for banks, although the differences in forbearance rates for bank and nonbank servicers of Ginnie Mae loans were more muted (see panels B and C).

Figure 2. Forbearance Take-up Rates

Source: eMBS and Black Knight Data and Analytics, LLC.

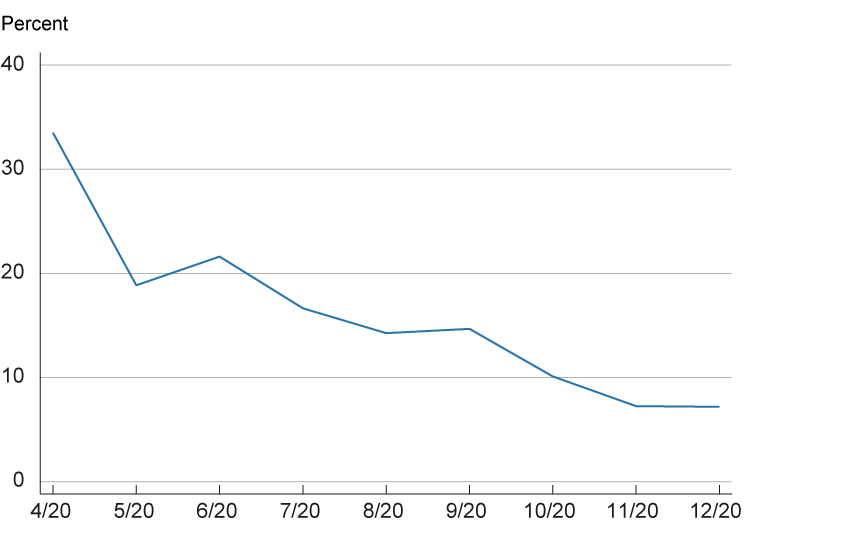

Not only did a fewer number of borrowers than anticipated request forbearance, not all borrowers with loans for which they had been granted forbearance stopped making their payments, as well. As shown in figure 3, in the early months of the pandemic, about 20 percent of borrowers with loans in forbearance were making payments. Once a borrower requests forbearance, they have the option not to make their loan payment for a number of months without having it impact their credit score or having the servicer initiate foreclosure. When their forbearance period ends, they can receive an extension or exit by either paying their missed payments, entering into a repayment plan, or having the missed payments tacked onto the end of the term of their mortgage. It is not clear why so many borrowers did not stop making payments while they had the option to freely do so. The CARES Act prevented interest being charged on forborne balances, meaning that forbearance was effectively an interest-free loan to those who received it.6 In more recent months, the share has decreased, at least in part because the borrowers that were able to continue making payments exited forbearance once their initial forbearance period ended.

Figure 3. Share of Forborne Balances Making Payments

Source: Black Knight Data and Analytics, LLC.

It is worth noting that the relatively low rate of forbearance uptake did not appear solely to be a result of federal supplemental unemployment insurance, since this support was ended at the end of July 2020, without any apparent increase in forbearance rates. Nor was there any apparent increase in forbearance rates in response to the second wave of COVID-19 cases in late fall.

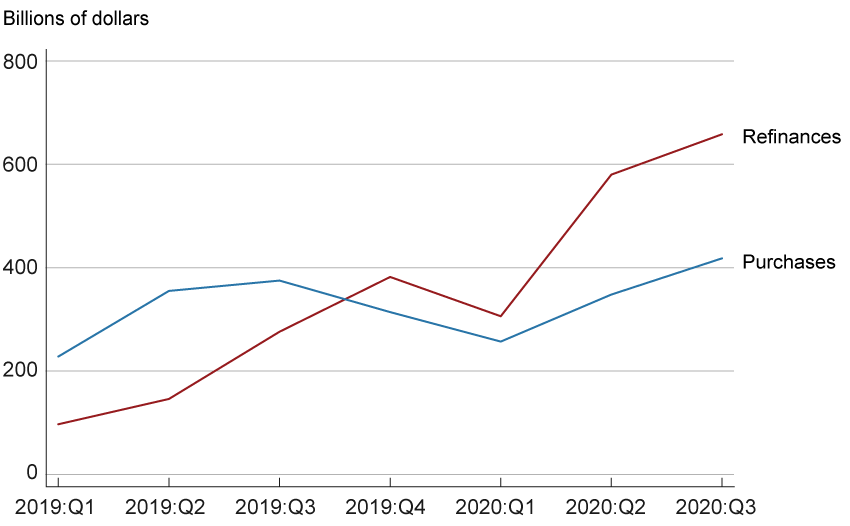

There Was a Refinancing Boom

All NBMCs with an origination pipeline benefited from the surprisingly active origination market. As seen in figure 4, mortgage purchase activity held steady during the pandemic, despite concerns that social distancing guidelines and work-from-home policies would reduce transactions. Lower interest rates also resulted in a refinancing boom, with total refinances increasing in both the second and third quarters of 2020. Income from mortgage originations, which comes largely as a lump sum at the closing of the loan, allowed NBMCs to cover shortfalls in servicing income because of payment advances. As an example, one of the largest nonbank mortgage servicers—Mr. Cooper—reported on its September 10-Q that its net gain on mortgages held for sale was over $1.5 billion during the first nine months of 2020, about twice the amount it reported for the first three quarters of 2019.

Figure 4.Aggregate Dollar Value of Purchase and Refinance Originations

Source: Mortgage Bankers Association and Haver Analytics.

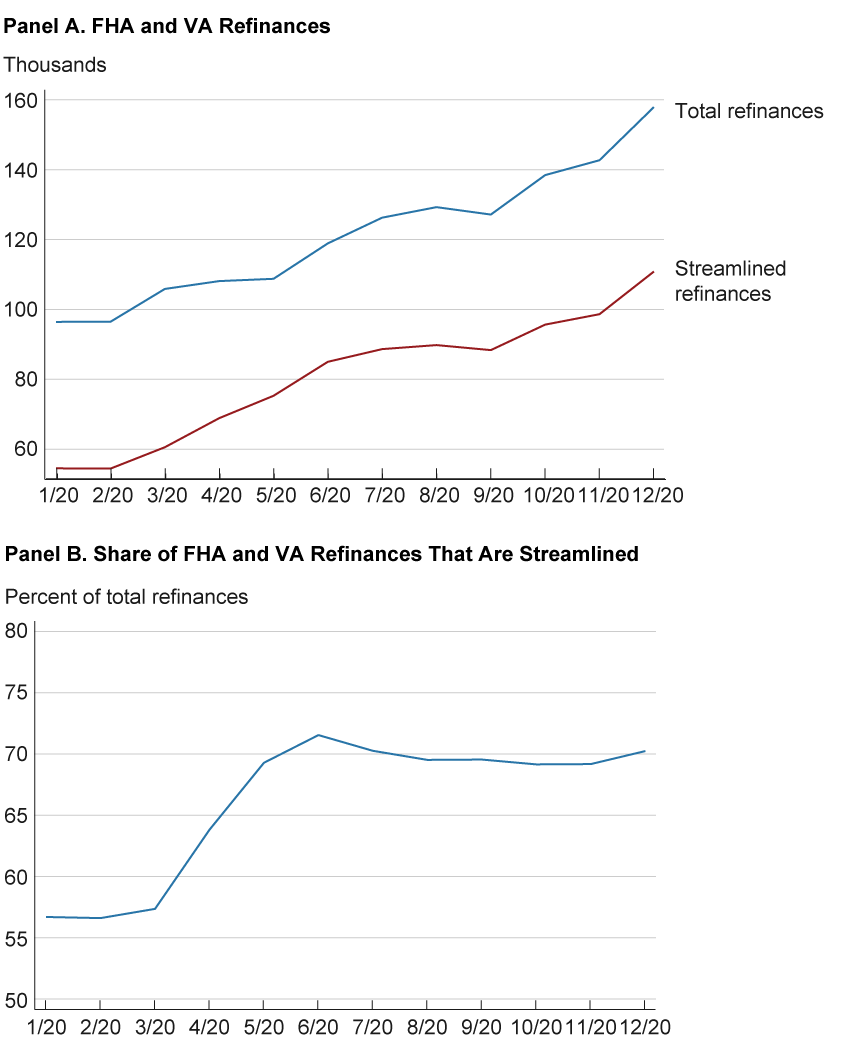

Interestingly, it was the NBMCs that originated loans sold into Ginnie Mae securities that possibly benefited the most from this boom because of the streamline refinance programs in place at the FHA and VA. These programs allow lenders to refinance existing FHA and VA loans without conducting any new underwriting or obtaining an appraisal on the home. Therefore, lenders could extend rate refinances without regard to whether borrowers had lost their jobs or whether the value of their homes had fallen. These new loans would then be placed into new Ginnie Mae mortgage-backed securities. In the wake of the pandemic, for example, FHA and VA streamline refinances increased in number and as a share of all FHA refinances (see figure 5).7

Figure 5. Streamlined Refinances of FHA-insured Single-Family Mortgages Streamlined Refinances of FHA-insured Single-Family Mortgages

Sources: eMBS and author's calculations.

[Update 7/8/2021: Panel A and Panel B were modified.]

GSEs, Ginnie Mae, and Related Government Agencies Adjusted Their Policies

GSEs, Ginnie Mae, and related government agencies made multiple changes to their policies and procedures to help mitigate any liquidity issues that arose during the pandemic. In the case of GSEs, these changes stopped short of a liquidity facility, but they did place a cap on the number of missed payments servicers were required to forward. In the case of Ginnie Mae loans, policies were more limited, but they provided an emergency backstop for servicers and a limited means of reimbursement for advances.

While Ginnie Mae is not in a position to reimburse servicers for advances, the agencies that insure the mortgages themselves (the FHA, VA, and RD) have some ability to do so. The FHA’s COVID-19 National Emergency Standalone Partial Claim Program and the USDA’s Mortgage Recovery Advance allow for issuers to make a borrower current by issuing a non-interest–bearing second lien for the total outstanding balance, including unpaid principal, interest, and escrow account payments. The FHA or RD then buys the second lien from the issuer, effectively reimbursing the issuer for the advance payments. These second liens can be issued without buying loans out of pools and therefore cause minimal disruption to the security investors.8

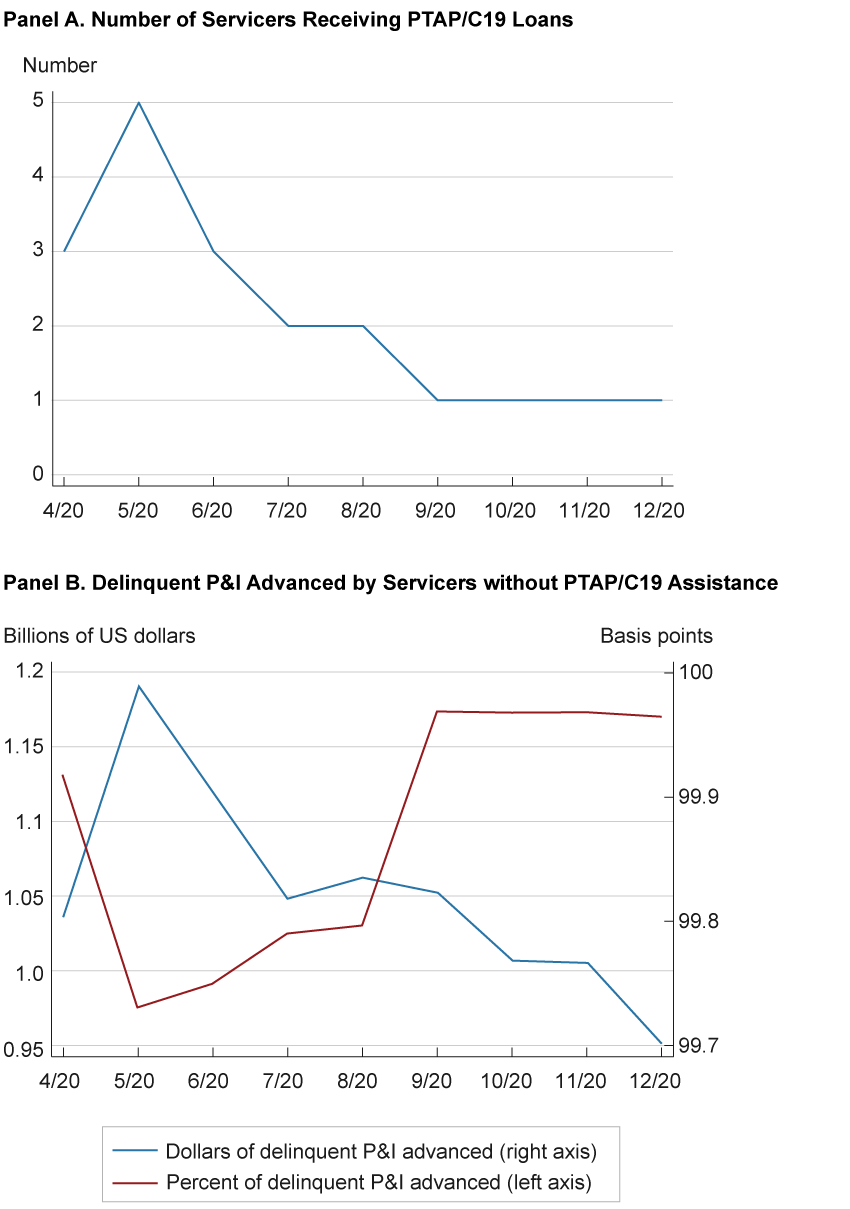

Ginnie Mae updated its liquidity facility—the Pass-Through Assistance Program (PTAP/C19)—so that servicers could use it for COVID-19–related assistance. The PTAP is a liquidity facility from which servicers needing short-term loans can borrow money so that they can forward payments. However, servicers could use PTAP only for assistance with the principal and interest components of borrowers’ mortgage payments; they could not access this liquidity facility to make tax and insurance payments, to pay for any insurance premiums, or to pay Ginnie Mae’s guarantee fee.9 However, borrowing from PTAP was minimal. Of the over $1 billion a month that Ginnie Mae servicers had to forward to owners of Ginnie Mae securities on behalf of delinquent borrowers, less than one-third of 1 percent came from the PTAP/C19 facility (see figure 6). The facility is still active, and as of December 2020 it was making loans to one servicer a month.10

Figure 6. Use of the Ginnie Mae PTAP Facility

Sources: Author’s calculations based on data from Ginnie Mae (available at https://www.ginniemae.gov/issuers/program_guidelines/pages/ptap.aspx).

Not all of Ginnie’s policy changes helped servicers. Ginnie Mae permits issuers to buy loans out of pools at par once they are three months delinquent,11 which is a way for issuers to avoid having to continue forwarding payments. Once the loans bought out of a Ginnie Mae security are performing, they can be repackaged into new securities. Since the issuer sells the loan into the security above par, it often makes a profit from this transaction. This practice of buying and repackaging was happening with such frequency that Ginnie Mae ended up restricting the repooling of loans until the loans had been performing again for at least six months.12 However, this is a practice that requires cash upfront and is therefore more suited to banks than to NBMCs.

The Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), which governs Fannie and Freddie, did not create a liquidity facility for mortgage servicers, but it did change other policies to provide relief to both servicers and originators. First, it required that Fannie Mae servicers only forward principal and interest payments for four months to match the policy already in place at Freddie Mac.13

The FHFA’s second policy change aided the origination market—a circumstance which is relevant to servicers because most also originate mortgages. While GSEs do not generally buy loans once the loans become delinquent, the GSEs announced in April 2020 that they would purchase loans that had entered forbearance prior to delivery, albeit for a fee.14 However, while this option wasn’t free, it did allow NBMCs to sell the loans, make good on their lines of credit, and remove the loans from their balance sheets.

Future Financial Stability and NBMCs

Some concerns raised by policymakers about NBMCs prior to the COVID-19 pandemic proved to be on target. As foreseen by Kim et al. (2018), the mortgage industry did lobby for the creation of a liquidity facility for nonbank mortgage servicers. However, in the end, the facility was neither created nor needed, as we learned after the fact.15 Other predictions and concerns raised prior to and at the beginning of the pandemic did not materialize. The fall in servicing income due to the need to advance payments did not become an existential threat. There was also relatively little action in terms of cancellation of warehouse lines of credit.16 According to Inside Mortgage Finance, the top 15 warehouse lenders all increased their committed lines of credit throughout 2020.

NBMCs were aided by low interest rates, a refinancing boom, and a surprisingly strong housing market. Their refinancing activities were aided by FHA and VA streamline refinance programs, which allowed the NBMCs to refinance loans to a lower rate without additional underwriting of the borrowers or appraisals of the properties. The fact that these programs effectively acted as an automatic stabilizer to nonbank servicers of FHA- and VA-insured mortgages is one more reason—among others—that GSEs may want to consider adopting a similar program, as suggested in Gerardi, Loewenstein, and Willen (2021).

In the near term, it does not appear that NBMCs present a concern. While refinancing activity has declined and may continue to do so, NBMCs have been surprisingly profitable during the pandemic. The secondary–primary mortgage rate spread—a measure of the profitability of originating mortgages—has remained high throughout the pandemic, most likely because of originator capacity constraints (Fuster et al., 2021). Forbearance rates have fallen, and the end of the pandemic is in sight.

In the longer term, the outlook is murkier. GSEs and Ginnie Mae have been aware of the risk presented by NBMCs for some time and are updating their requirements for their servicers in response.17 As the FHFA noted, it was updating its financial guidelines for servicers of GSE loans because “A critical improvement from the minimum financial requirements established in 2015 is addressing the risk factors related to servicing Ginnie Mae mortgages.”18 Many nonbank servicers of Freddie and Fannie loans also service loans in Ginnie Mae securities. These changes in guidelines should help mitigate liquidity concerns. In short, while legitimate concerns exist about NBMCs, no significant problems materialized during the COVID-19 pandemic for the reasons detailed above. However, one can imagine a shock with a less positive outcome: a situation in which servicing income is interrupted and there is no concurrent fall in interest rates and no increase in refinancing activity. While changes and discussions are already taking place in the industry to mitigate continuing concerns about NBMCs, more work may well be needed to understand their risk to the mortgage sector.

The views authors express in Economic Commentary are theirs and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The series editor is Tasia Hane. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. This paper and its data are subject to revision; please visit clevelandfed.org for updates.

Footnotes

- Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are GSEs because they were private companies that were created by Congress, although they are currently in conservatorship. In contrast, Ginnie Mae is a government-owned corporation within the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Return to 1

- However, the contractual ability of banks to shut off lines of credit varies by the type of credit line, specifically whether the line is committed or uncommitted. An uncommitted line can be rescinded, while a committed line is a legally binding agreement to lend. Return to 2

- MBS are groups of loans with certain characteristics that are pooled into one security. Investors purchase the security and receive a stream of income payments as people make their mortgage payments. Return to 3

- Unlike for servicers of Fannie and Freddie loans, originators of loans in Ginnie Mae securities are also almost always the issuers of those securities and also the servicers of those loans. By contrast, originators of Fannie and Freddie loans often sell the servicing rights to others, and it is GSEs themselves that issue the securities. Return to 4

- See “Fannie, Freddie Unlikely to Aid Mortgage Companies as Payments Dry Up, FHFA Chief Says” from the April 7, 2020, issue of the Wall Street Journal. Return to 5

- Despite that, there were reasons borrowers wanted to avoid forbearance, the main one being that borrowers in forbearance are not able to refinance. Return to 6

- [Update 7/8/2021: Footnote 7 was removed.] Return to 7

- The VA does not have such a program. Return to 8

- Principal and interest make up approximately 60 percent of the average monthly mortgage payment. Return to 9

- The facility is currently scheduled to remain open through the middle of 2021 for Ginnie Mae single-family loans, and through the end of 2021 for multifamily loans. Return to 10

- https://www.ginniemae.gov/issuers/program_guidelines/MBSGuideLib/Chapter_18.pdf. Return to 11

- https://www.ginniemae.gov/issuers/program_guidelines/Pages/mbsguideapmslibdisppage.aspx?ParamID=109. Return to 12

- See FHFA press release: https://www.fhfa.gov/Media/PublicAffairs/Pages/FHFA-Addresses-Servicer-Liquidity-Concerns-Announces-Four-Month-Advance-Obligation-Limit-for-Loans-in-Forbearance.aspx. Return to 13

- GSEs imposed steep loan-level price adjustments or post-settlement delivery fees (−500 basis points for first-time homebuyers and −700 basis points for “all other loans”) to these loans. These fees are adjustments to the price that GSEs pay a lender. For example, if a lender locks a $100 loan with a 3.25 percent note rate today, it can sell that forward in the to-be-announced (TBA) market for $103.95. If the borrower enters forbearance any time before the lender delivers the loan, the lender will receive only $103.95 − 700 basis points × $100 = $96.95, which is less than the $100 that the lender lent to the borrower. Return to 14

- In contrast, during the financial crisis of 2007–2008, servicing-advance asset-backed securities were included as an eligible asset class for the Term Asset Liquidity Fund (TALF), although its use was limited (Campbell et al., 2011). Return to 15

- JP Morgan Chase did limit the credit score qualifications for FHA loans that could be underwritten with its warehouse lines (see “JPMorgan Chase Caps Warehouse Credit” from the April 10, 2020, issue of Inside Mortgage Finance), but this did not result in a widespread reduction in credit to NBMCs. Return to 16

- GSEs updated their servicing agreements in 2015 to account for the potential risk posed by nonbank servicers (See https://www.fhfa.gov/Media/PublicAffairs/Pages/New-Eligibility-Requirements-for-SellerServicers.aspx.) Similarly, Ginnie Mae updated its requirements for issuers in 2014 (See https://www.ginniemae.gov/newsroom/Pages/PressReleaseDispPage.aspx?ParamID=94). The FHFA planned to update these agreements again in the first half of 2020, but plans to do so have been put on hold due to the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.fhfa.gov/Media/PublicAffairs/Pages/FHFA-to-Re-Propose-Updated-Minimum-Financial-Eligibility-Requirements-for-Fannie-Mae-and-Freddie-Mac-Seller-Servicers.aspx. Return to 17

- See https://www.fhfa.gov/Media/PublicAffairs/Documents/Servicer-Eligibility-FAQs-1302020.pdf. Return to 18

References

- Campbell, Sean, Daniel Covitz, William Nelson, and Karen Pence. 2011. “Securitization Markets and Central Banking: An Evaluation of the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility.” Journal of Monetary Economics, 58(5): 518–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2011.05.003.

- Fuster, Andreas, Aurel Hizmo, Lauren Lambie-Hanson, James Vickery, and Paul S. Willen. 2021. “How Resilient Is Mortgage Credit Supply? Evidence from the COVID-19 Pandemic.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 28843. https://doi.org/10.3386/w28843.

- Gerardi, Kristopher, Lara Loewenstein, and Paul S. Willen. 2021. “Evaluating the Benefits of a Streamlined Refinance Program.” Housing Policy Debate, 31(1): 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2020.1850014.

- Kim, You Suk, Steven M. Laufer, Richard Stanton, Nancy Wallace, and Karen Pence. 2018. “Liquidity Crises in the Mortgage Market.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2018(1): 347–428. https://doi.org/10.1353/eca.2018.0004.

Suggested Citation

Loewenstein, Lara. 2021. “Why Wasn’t there a Nonbank Mortgage Servicer Liquidity Crisis?” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary 2021-15. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-ec-202115

This work by Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International

- Share