- Share

Deep Wells Deep Pockets and Deep Impact

The shale gas industry brings both costs and benefits to the communities it pervades. But thought must be given, and plans should be laid, for when the industry leaves town.

Imagine: You live in a small rural community. Its once-thriving main street is now pockmarked with deserted storefronts. Its population, steadily dwindling. Its factories, shuttered by manufacturing’s decline. These problems, badly exacerbated by the Great Recession, have left your town reeling from high unemployment and shrinking tax revenues.

Now imagine that an industry with deep pockets walks in, promising to create jobs, replenish city coffers, and build wealth in your region. If this sounds too good to be true, it’s because it just might be.

These promises—coming from the oil and gas industry—have a price. In exchange for jobs, tax revenue, and wealth creation, the community must cope with costs like increased traffic, the potential for more expensive housing, and the risk of environmental degradation; combined, they can change the dynamics of the community.

What’s to be done?

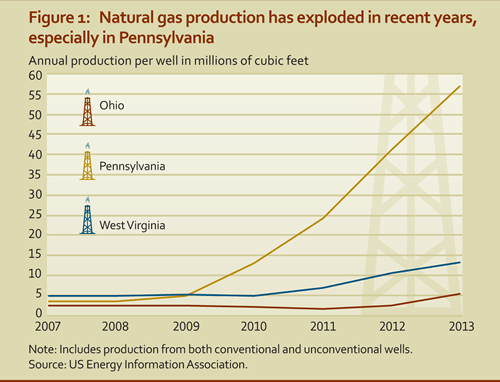

Communities across the country increasingly face this dilemma as the oil and gas industry, using new technology, has been aggressively pursuing previously unrecoverable deposits and igniting a boom in shale gas. This has been especially true in parts of the region the Cleveland Fed serves. Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia—each state can claim communities at various stages of the extraction process. The breakneck speed at which this development occurs makes it all the more important for a community to consider the long-run implications before drilling begins.

Immediate impact

Drilling for oil and gas is not necessarily new to Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, where thousands of conventional wells have been drilled since the mid-1800s. What is new is that the rate of drilling and volume of production have increased dramatically since unconventional drilling began a few years back (see figure 1). For example, a conventional vertical well produces around 250 cubic feet of natural gas per day. A hydraulically fractured well, though exponentially more expensive, produces four to five million cubic feet per day.

Costs. Although increased production is a boon for the oil and gas industry, it subjects communities to more concentrated, intense drilling than ever before. For example, a shale gas well typically requires hundreds of trucks to ferry water, sand, pipe, and other supplies back and forth. This traffic rapidly degrades roads and bridges, congests streets, and increases the risk of accidents.

Often, outside of states such as Texas and Oklahoma, which have historically been centers of oil and gas drilling expertise, a region’s workforce lacks the skills the industry requires. Out-of state workers must be imported, filling hotels, campgrounds, and the few available rental units. In rural communities, the increased demand for scarce rentals may raise rents, pricing current residents out of the market.

Benefits. The increased production can also be a boon for some community residents. The terms for leasing mineral rights typically include a signing bonus and a royalty percentage awarded to landowners, based on the volume of oil and gas recovered on the property. According to a case study of Carroll County by Policy Matters Ohio, signing bonuses could be up to $5,800 per acre and royalty payments to at least 12.5 percent. Landowners, some of whom became millionaires overnight, are paying off mortgages and buying farm equipment and other durable goods.

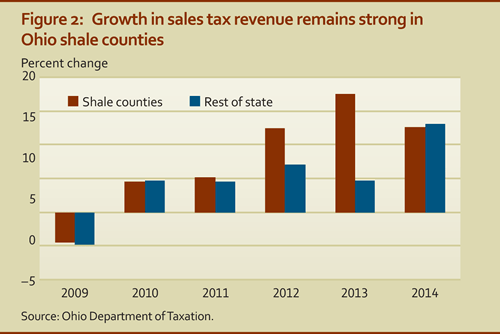

The influx of workers from outside the region fills local restaurants and hotels and can create new businesses or enable existing ones to expand. This beefed-up purchasing can bolster sales tax revenues, and the leasing of land by cities and school districts can ease tight budgets. Figure 2 shows the change in sales tax revenue for the eight Ohio counties where most of the state’s drilling occurs, compared with the rest of Ohio. Although growth in sales tax revenue is now comparable to the rest of the state, it remains strong.

Longer-term implications

Two specific issues have the potential to jolt a community in the long run: the boom–bust cycle and what is known as the natural resource curse. Because the supply of oil and gas is finite, it tends to create a boom‒bust cycle with three stages: First, a flurry of activity as drilling begins and infrastructure is built. Next, a period of slower development as drilling slows while production plateaus and enters a maintenance period. And finally, the bust, when production stops and the industry moves out of the region.

The natural resource curse is the tendency for a region’s strong dependence on one industry to crowd out investment in others. It also increases economic volatility as the region is tied to the success of a single commodity, such as coal, oil, or natural gas and subject to international price fluctuations. For example, the presence of the oil and gas industry may move investment into industries that supply the products it needs; the well-paid jobs it offers may induce workers to migrate out of other industries. The problems arise when the dominant industry exits the region, leaving behind underdeveloped industries and few job opportunities for the newly unemployed workers. The sharp decline in oil and gas prices through the second half of 2014 illustrates this point. As prices fell by more than 50 percent, oil and gas companies began cutting their 2015 drilling budgets, the number of drilling rigs declined, and communities are uncertain about what future investment to expect.

What can a community do?

An extensive body of literature has examined the impact of natural resource extraction on communities from many angles: sociologically, economically, environmentally, and politically. Impacts vary among regions, each managing its economic development in its own way. That said, the literature suggests next steps that are applicable to most regions. For one, communities need to consider the industry’s likely long- and short-run impacts.

In the short run. Joe Campbell, a research associate at the Ohio State University Extension, recently examined how communities in Jefferson County, Ohio, are coping with short-run growth in shale drilling as the early flurry of leasing slows and drilling begins. There, it has been important to identify the key players who will be affected by the growth and to convene regular meetings among them. Players include elected officials, business leaders, citizens, and community groups.

Other lessons learned are the importance of understanding that the oil and gas industry moves quickly and is dependent on global prices, not necessarily on local concerns. However, it is still important to engage regularly with industry representatives, ideally with a united community voice, to understand their plans and cultivate a relationship that may help the community in the future.

In the long run. Planning for the long run is more difficult. A community’s resources tend to be stretched during the boom, leaving little time to plan for the future. The unpredictable length of the boom also introduces uncertainty about how far ahead the community needs to plan. Communities would benefit from thinking about how they can retain wealth from the natural resource boom and to prepare for life after the drilling and extraction ends. One approach is for communities to develop ways to diversify their economies so that the oil and gas industry’s departure does not lead to a mass exodus of population and capital, leaving communities with expanded and underutilized infrastructure to maintain.

Another idea that has already had some success is to develop programs to teach residents the skills they will need for relatively high-paying jobs in the oil and gas industry. One regional program that facilitates this effort is ShaleNET, which was developed at Westmoreland County Community College in southwest Pennsylvania using a $5 million grant from the US Department of Labor.

ShaleNET consulted with the industry’s major employers to develop a curriculum that fits their hiring needs. This highly regarded program has since expanded to include four community colleges in three states (Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas). According to its website, ShaleNET has trained more than 5,000 participants, 3,400 of whom have found employment. Given the uncertainty about the life span and labor requirements of the shale boom, entities like ShaleNET must be nimble enough to adjust their programs to meet the industry’s needs.

Another approach is to establish a future fund, at the state level, that will tax the industry according to the volume of gas and oil extracted, setting the proceeds aside for economic development, environmental remediation, and re-energizing a community’s economy after the boom ends. An example is North Dakota’s Legacy Fund, which, as of April 2014, had a balance of nearly $2 billion. This fund will continue to accumulate until June 2017, when state lawmakers will decide how to utilize it. Currently, Ohio is considering changes to the structure of its oil and gas taxes, which would set aside a small percentage to create a legacy fund for use after 2025.

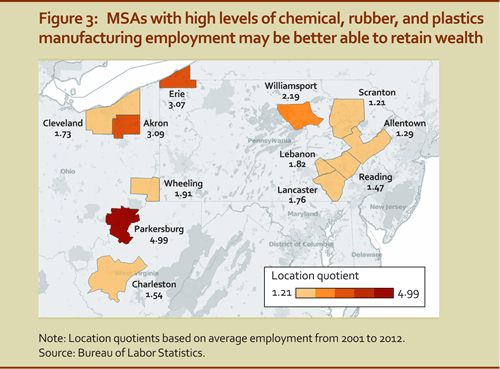

Lastly, a region may capitalize on existing industries’ ability to take advantage of the proximity and range of chemical components that can be extracted and used in the chemical and plastics manufacturing industries. Several of the region’s metropolitan areas (see figure 3) have above-average employment in those industries, and expanding them may help to retain more wealth in the region. It is still too early to tell how much these industries in the region will benefit. Infrastructure to transport gas is still being constructed, and decisions about processing facilities are still being made. However, Ohio’s economic development agency is working with a local university to better understand how the shale gas boom can leverage the region’s expertise in plastics and chemical manufacturing.

Over the next year, the Cleveland Fed will host roundtables in communities across southeastern Ohio and southwestern Pennsylvania, where the oil and gas industry has been most active. Our purpose is to begin a conversation among key stakeholders that will continue as the impact of the oil and gas industry matures.