- Share

Consumers and COVID-19: Survey Results on Mask-Wearing Behaviors and Beliefs

Masks or cloth face coverings have the potential to help reduce the spread of COVID-19 without greatly disrupting economic activity if they are widely used. To assess the state of mask wearing, we surveyed US consumers about their recent and prospective mask-wearing behavior. We find that most respondents are wearing masks in public but that some respondents are less likely to follow social-distancing guidelines while doing so, indicating a potential tradeoff between two of the recommended methods that jointly reduce coronavirus transmission. While most respondents indicated that they were extremely likely to wear a mask if required by public authorities, the reported likelihood is strongly dependent on age and perceived mask efficacy.

The views authors express in Economic Commentary are theirs and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The series editor is Tasia Hane. This paper and its data are subject to revision; please visit clevelandfed.org for updates.

The novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19 continues to spread in the United States. After an initial burst of confirmed or probable cases of COVID-19 in late March and early April 2020, the number of new cases trended down through mid-June, before starting to quickly pick up again.1 By early July 2020, the daily count of new confirmed cases in the United States had risen to a level above its April peak.

With economic activity severely and adversely affected by broad-based shutdowns to stem the initial surge in COVID-19 cases, policymakers are eager to find more targeted ways to reduce the number of new cases; see, for example, Governor’s Economic Advisory Board (2020). The broad usage of masks or other cloth face coverings appears to hold promise in this regard. A variety of evidence suggests that masks can help reduce the transmission of the novel coronavirus; at the time of this writing, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended the usage of masks or face coverings in public settings and when around people who do not live in one’s own household, especially when other social-distancing measures are difficult to maintain.2 To the extent that masks or face coverings are widely worn, they can potentially help to improve public health outcomes at a relatively low cost in terms of foregone economic activity when compared with alternative approaches, such as mandated closures of segments of the economy.3

As part of the Consumers and COVID-19 survey project sponsored by the Cleveland Fed, we recently asked consumers about their mask-wearing behavior and beliefs, given the emerging consensus that wearing a mask or other makeshift face covering that covers the nose and mouth can help to inhibit the spread of the novel coronavirus. We found that the vast majority of respondents had worn a mask or face covering the last time they went out in public to an indoor space, even though not all were required by state or local ordinance to do so. In addition, when conducting a common activity such as shopping at a store, most felt more comfortable when employees and other patrons were wearing masks, and there was widespread agreement that wearing a mask was helpful in reducing the spread of the coronavirus. However, a large minority of our respondents—about one-quarter—reported that wearing a mask made them less likely to follow social-distancing guidelines, indicating a potential tradeoff for some individuals between two of the recommended methods to reduce the transmission of the coronavirus. While most respondents reported that they were extremely likely to wear a mask if required to do so by public authorities, we find that adherence to mask wearing is strongly age-dependent, with older respondents markedly more likely to wear masks than younger respondents. Respondents who thought that wearing a mask was effective at reducing the spread of the coronavirus were also much more likely to wear one if doing so were required by public authorities. These findings strengthen the case for conducting further research on the benefits of mask wearing and clearly communicating those findings to the public.

Survey Design

Our survey questions on mask usage were a module within a larger project that focuses on the beliefs of individual US consumers, following Dietrich et al. (2020) and Knotek et al. (2020). The survey is administered on the Qualtrics Research Core Platform, and Qualtrics Research Services recruits a nationally representative sample of participants to provide responses. All respondents are required to be US residents, fluent in English, and 18 years of age or older. Individuals in the survey are anonymized to ensure confidentiality. Dietrich et al. (2020) present information on some of the background characteristics of the survey respondents.

For the mask-related questions that are the focus of this Commentary, we surveyed a total of 1,141 respondents across the United States between July 3 and July 7, 2020. Our survey module asked a total of 11 questions, with two of those questions containing multiple parts. Many of our questions asked respondents to select an answer from a limited set of options. Knotek et al. (2020) discuss some of the other questions in the survey, which are used to provide ongoing updates to the Consumers and COVID-19 section on the Cleveland Fed’s website.

Survey Results

Table 1 compactly summarizes most of the survey questions and the associated percentage of respondents who selected a particular answer to those questions. We present the remaining questions and their answers in more detail in the text below.

| Question | Answer options | Percent of responses |

| Question 1: Did you wear a mask or other face covering the last time you went out in public to an indoor space, such as shopping in a grocery store? | Yes | 89.9 |

| No | 10.1 | |

| Question 2: For those who selected “No” to the prior question: If masks were provided for free when entering a store, would you wear one? | Yes | 33.0 |

| No | 67.0 | |

| Question 4: Where you live, is it required for most adults to wear a mask or face covering in public spaces, such as grocery stores? | Yes | 74.1 |

| No | 22.7 | |

| Not sure | 3.2 | |

| Question 6: When at a store, do you feel more comfortable, less comfortable, or indifferent if employees are wearing masks? | More comfortable | 67.4 |

| Less comfortable | 11.1 | |

| Indifferent | 21.5 | |

| Question 7: When at a store, do you feel more comfortable, less comfortable, or indifferent if other shoppers are wearing masks? | More comfortable | 70.4 |

| Less comfortable | 10.1 | |

| Indifferent | 19.5 | |

| Question 8: Does wearing a mask help to reduce the spread of the coronavirus? | Yes, a lot | 47.2 |

| Yes, some | 31.8 | |

| Not sure | 15.1 | |

| No, it does nothing | 4.8 | |

| No, it increases the spread | 1.1 | |

| Question 9: Does wearing a mask make you less likely to follow social-distancing guidelines? | Yes | 24.1 |

| No | 67.9 | |

| Not sure | 8.0 |

Notes: Survey responses from 1,141 respondents surveyed between July 3 and July 7, 2020.

Source: Consumers and COVID-19, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

The vast majority—almost 90 percent—of respondents reported that they had worn a mask or face covering the last time they went out in public to an indoor space (Question 1). In fact, the share of respondents indicating that they had worn a mask the last time they were out in public was higher than the share who indicated that wearing a mask was required in the area in which they lived (74 percent, in Question 4). This result suggests that, at least in some cases, people have changed their behavior voluntarily in response to perceived health risks from the coronavirus pandemic.

Among those who answered that they had not worn a mask the last time they went out in public, one-third indicated that they would wear masks if they were provided for free when entering a store (Question 2). These responses suggest that simple interventions, such as providing masks for free at store entrances, may prove sufficient to nudge some but not all individuals to change behavior.

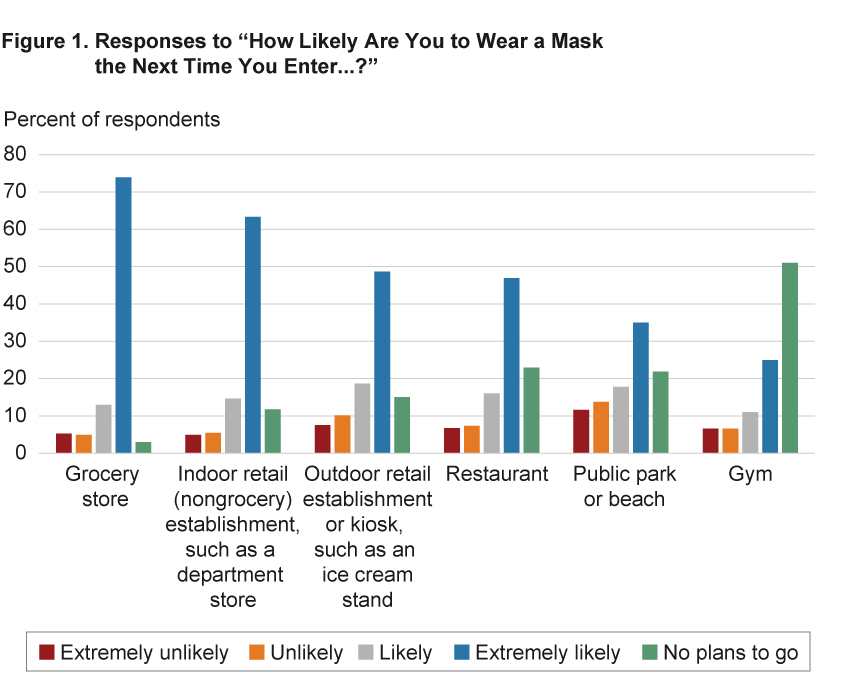

We asked consumers about how likely they were to wear a mask in various situations, focusing on six common settings, listed in Question 3 below. For each setting, respondents chose from among the following options: “Extremely unlikely,” “Unlikely,” “Likely,” “Extremely Likely,” or “No plans to go.”

Question 3: “How likely are you to wear a mask the next time you enter:

- (a) Grocery store

- (b) Indoor retail (nongrocery) establishment, such as a department store

- (c) Outdoor retail establishment or kiosk, such as an ice cream stand

- (d) Restaurant

- (e) Public park or beach

- (f) Gym”

Figure 1 plots the distributions of responses to each part of this question about anticipated behavior. For indoor shopping experiences, the vast majority of respondents reported being either likely or extremely likely to wear a mask. But attitudes shifted for outdoor activities or going to restaurants, where fewer respondents were as strongly committed to wearing a mask. That said, the option “No plans to go” in some cases may capture nonparticipation as an alternative strategy to avoid exposure to the coronavirus, as a stark alternative to wearing a mask. For example, going to a grocery store may be essential for most individuals, whereas going to a restaurant, where one would need to take off a mask to eat, might be perceived as riskier. The response “No plans to go” may also capture an inability to go to some of the options listed if state or local authorities have closed such establishments or activities because of public health concerns; the response may also capture personal preferences to not attend the location in question even in normal times, as well as other reasons.

Source: Consumers and COVID-19, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

About three-quarters of respondents believed that it was required for most adults to wear a mask or face covering in a public space, such as a grocery store, where they lived (Question 4). Given the surge in new cases immediately prior to our survey period, it is worth noting that mask-wearing mandates were changing rapidly, and it is impossible to know whether all respondents would have had complete information about the latest changes to state or local mask-wearing mandates when they responded to the survey. In addition, mask-wearing mandates vary widely across the nation and sometimes differ from one city to another nearby city.4 For this reason, we find respondents’ impressions of mandates to be highly informative, even if they are perhaps imperfect.

About two-thirds of respondents indicated that mask wearing made them feel more comfortable in retail settings, as captured in Question 6 and Question 7, which asked about store employees’ mask wearing and other shoppers’ mask wearing, respectively. And about 80 percent of respondents thought that wearing a mask had some type of beneficial effect in terms of reducing the spread of the coronavirus, as captured in Question 8. These results suggest that stores in the retail sector may stand to benefit from broad-based mask wearing because most customers believe that it provides for a safer shopping experience. About 15 percent of respondents were not sure whether wearing masks helps to reduce the spread of the coronavirus, uncertainty which may not be surprising given the shifting guidance on mask wearing (see footnote 2) and the fact that much remains unknown about this novel coronavirus and the disease it causes, COVID-19.

It is possible that wearing a mask can lead to changes in behaviors. In response to Question 9, 24 percent of respondents self-reported that wearing a mask made them less likely to follow social-distancing guidelines. This finding raises the possibility that, at least for some individuals, they may see a tradeoff between two of the recommended measures to reduce the transmission of the coronavirus. Yet the current view of the World Health Organization (WHO) is that these two measures, along with frequent hand-washing and avoiding touching one’s face and mask, should be viewed as complementary.5

We also asked two other questions not reported in the table. Question 10 is the following: “In your view, how common is COVID-19 where you live?” Respondents chose a number on a slider from 0 to 100, where 0 was described as “No cases” and 100 was described as “Many cases.” The median response was 52, suggesting that the respondent in the middle of the distribution of responses viewed the number of cases in his or her area as being about in the middle of this spectrum. Question 11 is the following: “In your view, how likely do you think it is that resuming normal activities will expose you to the coronavirus?” Respondents again chose a number on a slider from 0 to 100, where 0 was described as “Extremely unlikely” and 100 was described as “Extremely likely.” In this case, the median response was 64, implying that the typical respondent in the middle of the distribution perceived some risk of being exposed to the coronavirus by resuming normal activities.

While interesting in their own right, we next use the above responses further to investigate how people might react to stricter mask-wearing requirements by government authorities.

Will People Follow Mask Mandates?

Based on the economic concept of revealed preference, the fact that many respondents indicated that they wore a mask the last time they went out in public suggests that they would likely be open to wearing masks if masks were required by government authorities. To pursue this idea, we asked the following question:

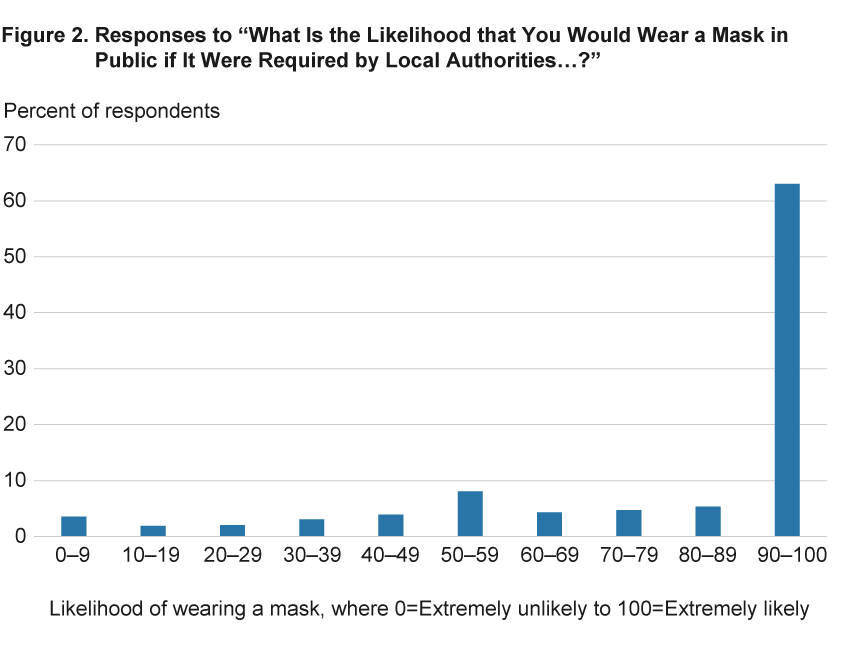

Question 5. “Using the slider, where 0 = “extremely unlikely” and 100 = “extremely likely,” what is the likelihood that you would wear a mask in public if it were required by:

- (a) Local authorities

- (b) State authorities

- (c) Federal authorities”

The median response was 100 (“extremely likely”) for each of the questions if the requirement were imposed by local, state, or federal authorities. The mean responses were 81 for each of the three levels of government. In other words, most people report that they would be likely or extremely likely to wear a mask regardless of the government authority requiring it.6 However, there is some dispersion in views about how likely people would be to wear a mask if it were required. Figure 2 shows a histogram of responses to the question about a requirement announced by local authorities; the figures for requirements from state authorities and federal authorities were very similar. While more than 60 percent of survey respondents reported values in the range of 90 to 100, near the “extremely likely” endpoint, we see responses across the entire spectrum.

Source: Consumers and COVID-19, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

To quantitatively assess the factors driving consumers’ likelihood to follow mask-wearing mandates, we ran a regression to explain the reported likelihood that each individual j would wear a mask if required by local authorities.7 To explain this reported likelihood, we included in our regression as explanatory variables a number of pieces of information from our survey, including the individual’s age, his or her beliefs about how effective masks are in helping to reduce the spread of the coronavirus, and other survey beliefs about current mask requirements, how common COVID-19 is in his or her area, and potential exposure to coronavirus from resuming normal activities. As additional control variables that were not in the survey, we also included data on the number of new COVID-19 cases in the individual’s state of residence over the past 14 days and the population density of the individual’s zip code of residence. Table 2 lists the variables used in our regression and displays the results.8

| Question | Coefficient | Standard error | Marginal effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 0.031*** | 0.004 | 0.39 |

| 2. Mask effectiveness: Yes, a lot | 1.424*** | 0.287 | 17.36 |

| 3. Mask effectiveness: Yes, some | 0.867*** | 0.276 | 9.56 |

| 4. Mask effectiveness: Not sure | 0.298 | 0.284 | 3.38 |

| 5. Mask effectiveness: No, it increases the spread | −0.950*** | 0.420 | −15.74 |

| 6. Reported masks mandatory | 0.290** | 0.133 | 3.74 |

| 7. Reported commonality of COVID-19 | 0.006** | 0.002 | 0.07 |

| 8. Exposure upon resuming normal activities | 0.015*** | 0.003 | 0.18 |

| 9. Reported wearing a mask makes less likely to social distance | −0.667*** | 0.125 | −9.37 |

| 10. Statewide new COVID-19 cases per million over past 14 days | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.01 |

| 11. Log zip-code population density | −0.029 | 0.065 | −0.36 |

| Observations | 1,099 | ||

| Log pseudolikelihood | −369.96 |

Notes: The fractional logit regression includes a constant and day fixed effects (not reported). The mask effectiveness response “No, not at all” is the omitted variable. ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1 percent, 5 percent, and 10 percent levels. Robust standard errors are reported. Marginal effects are calculated at the sample means and are transformed to the 0–100 point scale asked in the original question.

Source: Consumers and COVID-19, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

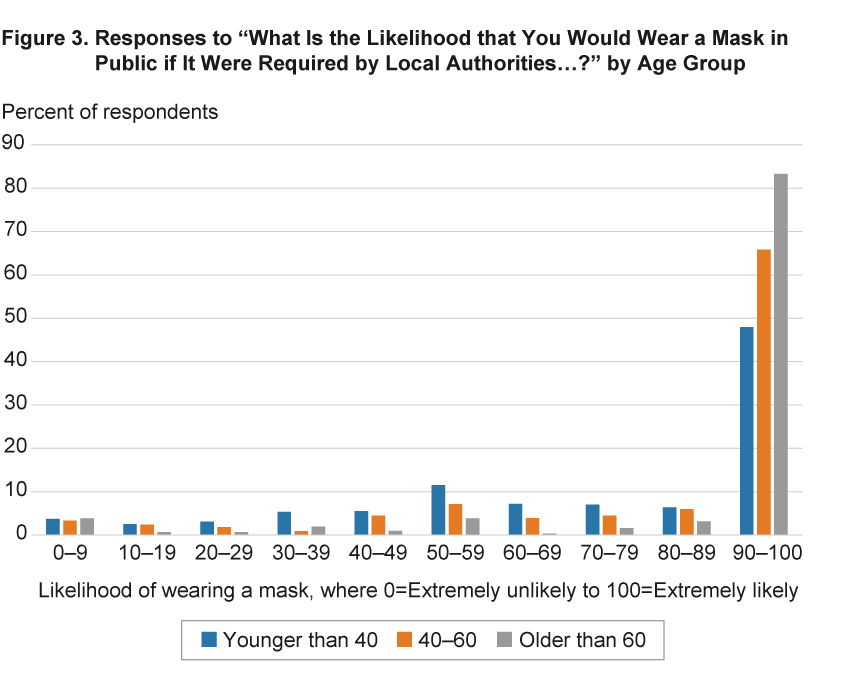

We find strong evidence that older respondents are more likely to follow mask-wearing requirements than are younger respondents. Quantitatively, the likelihood reported by a 60-year-old survey respondent is about 15.6 points higher on our 0 to 100 scale than the likelihood reported by a 20-year-old survey respondent, on average. These results may not be surprising given that mortality rates from COVID-19 are much higher for older individuals than for younger individuals.9 But they are also consistent with the recent rapid growth in new COVID-19 case counts among younger individuals, who appear more reluctant to wear masks based on our survey results. As such, they highlight the challenge for policymakers to influence the behavior of younger groups to wear masks to prevent further spread of the coronavirus to more vulnerable populations. Figure 3 shows this phenomenon graphically, where we have separated respondents into three groups based on age: those younger than 40, those between 40 and 60, and those older than 60. There are markedly different patterns of responses among these three age groups in terms of the likelihood of wearing masks in response to government requirements.

Source: Consumers and COVID-19, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

We also find strong evidence that individuals’ beliefs over the efficacy of masks is highly correlated with their likelihood of adhering to mask requirements. Individuals who indicated in Question 8 that wearing masks helped “a lot” or “some” in reducing the spread of the coronavirus were far more likely to follow mask-wearing requirements (by +17.4 points and +9.6 points, respectively) than were those who believed that wearing masks does “nothing,” which is the omitted group in the regression. Individuals who reported that they were “not sure” whether wearing masks helps to reduce the spread of the coronavirus reported likelihoods of following mask-wearing requirements that were little different from those who believed that wearing masks does “nothing.” There would appear to be an opportunity to provide information to this “not sure” group to increase their mask-wearing behavior. By contrast, individuals who believed that wearing masks increases the spread of the virus were far less likely to adhere to mask-wearing requirements (by −15.7 points). These results strengthen the case for conducting further research on the benefits of mask wearing and clearly communicating those findings to the public in order to get their buy-in and make mask-wearing requirements highly successful.

Individuals who reported that masks were already mandatory where they live (Question 4) and who perhaps had become accustomed to them, individuals who believed that COVID-19 cases were relatively more common in their area (Question 10), or individuals who believed that they would be relatively more exposed to the novel coronavirus if they resumed their normal activities (Question 11) were all more likely to adhere to mask-wearing requirements.

By contrast, individuals who reported that wearing a mask makes them less likely to follow social-distancing guidelines were also less likely (by −9.4 points) to wear a mask if required by local authorities compared with the group that did not see a tradeoff between mask wearing and social distancing. On the surface, this relationship may suggest that these individuals may be less risk averse than others or that the experience with wearing a mask has made them more comfortable reengaging in prior behaviors, either without masks or without social distancing. The latter possibility raises the specter of moral hazard, in which individuals are not fully internalizing the consequences of their actions on others. But we acknowledge that many interpretations are possible and believe it is an important avenue for further research.

We found no statistically significant relationship between the likelihood of adhering to mask-wearing requirements and official statistics on state-level new COVID-19 case counts, which often receive prominent news coverage. Similarly, there was no statistically significant relationship between the likelihood of adhering to mask-wearing requirements and the population density of the zip code in which the individual lives, even though people living in more densely populated areas may be more exposed to the coronavirus via shared spaces and public transportation.10

Conclusion

This Commentary provides survey evidence on recent and prospective mask-wearing behavior and beliefs by consumers. Masks or cloth face coverings have the potential to help in reducing the transmission of the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19 to the extent that they are widely used. We found that the vast majority of respondents reported having worn a mask the last time they went out in public to an indoor space, even though not all were required to do so. In addition, most felt more comfortable when employees and other shoppers were wearing masks, and there was widespread agreement that wearing a mask was helpful in reducing the spread of the coronavirus. However, about one-quarter of our respondents indicated that wearing a mask made them less likely to follow social-distancing guidelines. While most respondents indicated that they were extremely likely to wear a mask if doing so were required by public authorities, we find that adherence to mask wearing is strongly age-dependent, with older respondents markedly more likely to wear masks than younger respondents. Respondents who thought that wearing a mask was effective at reducing the spread of the coronavirus were also much more likely to wear one if doing so were required by public authorities. These findings strengthen the case for conducting further research on the benefits of mask wearing and clearly communicating those findings to the public.

Footnotes

- Databases maintained by both The New York Times and Johns Hopkins University & Medicine provide generally similar estimates of confirmed COVID-19 cases and recent trends. Return to 1

- For evidence on the effectiveness of masks, see, for example, Chu et al. (2020), Mitze et al. (2020), and Lyu and Wehby (2020). For the most recent guidance from the CDC, see https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cloth-face-cover-guidance.html (accessed July 12, 2020). The World Health Organization’s (WHO) current advice is that “Non-medical, fabric masks are being used by many people in public areas, but there has been limited evidence on their effectiveness and WHO does not recommend their widespread use among the public for control of COVID-19. However, for areas of widespread transmission, with limited capacity for implementing control measures and especially in settings where physical distancing of at least 1 metre is not possible — such as on public transport, in shops or in other confined or crowded environments — WHO advises governments to encourage the general public to use non-medical fabric masks.” See “What is WHO’s view on masks” on the Q&A: Masks and COVID-19 section of the WHO’s website at https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/q-a-on-covid-19-and-masks (accessed July 12, 2020). However, it is worth noting that views on wearing masks have shifted radically over time as more information on the novel coronavirus has come to light. Early on in the spread of the coronavirus in the United States, the CDC, the WHO, and the US Surgeon General were opposed to most people’s wearing masks; see Goodnough and Sheikh (2020) and Pancevski and Douglas (2020). Return to 2

- See Hatzius, Struyven, and Rosenberg (2020). Return to 3

- During our survey period, based on data compiled by the website https://masks4all.co/what-states-require-masks/, we estimate that about 60 percent of the US population resided in states that had some form of a statewide mask requirement, though the exact form of those requirements manifested variously across states. About 37 percent of the US population resided in states that had some form of mask requirements that applied to parts of the state. Return to 4

- As of the date of this writing, the WHO’s view on masks was as follows: “Masks should be used as part of a comprehensive strategy of measures to suppress transmission and save lives; the use of a mask alone is not sufficient to provide an adequate level of protection against COVID-19. You should also maintain a minimum physical distance of at least 1 metre from others, frequently clean your hands and avoid touching your face and mask.” See “What is WHO’s view on masks” on the Q&A: Masks and COVID-19 section of the WHO’s website at https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/q-a-on-covid-19-and-masks (accessed July 12, 2020). Return to 5

- The medians and means look across individuals. For each individual, we also calculated the differences between his or her state and local responses, and between his or her federal and local responses, and then took means and medians; these were close to zero, indicating little distinction at the individual level—on average—across the authority imposing the mask-wearing requirement. Return to 6

- The results were qualitatively and quantitatively similar if we used the likelihood if masks were required by state or federal authorities. Return to 7

- Because individuals select likelihood measures using a slider for values from 0 to 100 inclusive, with many responses piled at the 100 endpoint as shown in figure 2, we transform these responses to a [0,1] range and estimate the regression using a fractional logit model. Marginal effects reported in the table are calculated at the sample means and are transformed back to the 0–100 point scale asked in the original question. Return to 8

- Using data from Germany, Mitze et al. (2020) show that mask-wearing mandates had the largest relative effect on COVID-19 case counts among older-age cohorts that are at highest risk. Return to 9

- A somewhat higher proportion of respondents from low-population-density areas gave responses ranging from 0 to 49 (toward the “extremely unlikely” end of the spectrum) compared with respondents from higher-population-density areas. But the proportions of respondents at the top of the likelihood scale (in the range of 90–100) were fairly similar across respondents from different population density areas. Return to 10

References

- Chu, Derek K., Elie A. Akl, Stephanie Duda, Karla Solo, Sally Yaacoub, Holger J. Schünemann, et al. 2020. “Physical Distancing, Face Masks, and Eye Protection to Prevent Person-to-Person Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Lancet, 395(10242): 1973–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9.

- Dietrich, Alexander M., Keith Kuester, Gernot J. Müller, and Raphael S. Schoenle. 2020. “News and Uncertainty about COVID-19: Survey Evidence and Short-Run Economic Impact.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Working Paper No. 20-12. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-wp-202012.

- Goodnough, Abby, and Knvul Sheikh. 2020. “C.D.C. Weighs Advising Everyone to Wear a Mask.” The New York Times (March 31). Accessed July 10, 2020. https://nyti.ms/2UPafd0.

- Governor’s Economic Advisory Board. 2020 “Face Coverings Can Help Save Lives and Protect Ohio’s Economy, Too.” Crain’s Cleveland Business (July 10). Accessed July 10, 2020. https://www.crainscleveland.com/opinion/face-coverings-can-help-save-lives-and-protect-ohios-economy-too.

- Hatzius, Jan, Daan Struyven, and Isabella Rosenberg. 2020. “Face Masks and GDP.” Goldman Sachs Global Economics Analyst (June 29). https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/pages/face-masks-and-gdp.html.

- Knotek, Edward S., II, Raphael S. Schoenle, Alexander M. Dietrich, Keith Kuester, Gernot J. Müller, Kristian Ove R. Myrseth, and Michael Weber. 2020. “Consumers and COVID-19: A Real-Time Survey.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary, 2020-08. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-ec-202008.

- Lyu, Wei, and George L. Wehby. 2020. “Community Use of Face Masks and COVID-19: Evidence from a Natural Experiment of State Mandates in the US.” Health Affairs, 39(8): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00818.

- Mitze, Timo, Reinhold Kosfeld, Johannes Rode, and Klaus Wälde. 2020. “Face Masks Considerably Reduce COVID-19 Cases in Germany: A Synthetic Control Method Approach.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 13319, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA). https://ideas.repec.org/p/iza/izadps/dp13319.html.

- Pancevski, Bojan, and Jason Douglas. 2020. “Masks Could Help Stop Coronavirus. So Why Are They Still Controversial?” The Wall Street Journal (June 29). Accessed July 10, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/masks-could-help-stop-coronavirus-so-why-are-they-still-controversial-11593336601.

Suggested Citation

Knotek, Edward S., II, Raphael S. Schoenle, Alexander M. Dietrich, Gernot J. Müller, Kristian Ove R. Myrseth, and Michael Weber. 2020. “Consumers and COVID-19: Survey Results on Mask-Wearing Behaviors and Beliefs.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary 2020-20. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-ec-202020

This work by Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International