- Share

The Shifting Source of New Business Establishments and New Jobs

As markets and business patterns change, new business establishments are created to serve them. Those new establishments can be provided by entrepreneurs creating new firms or by the owners of existing businesses opening new locations. We show that over the past three decades, new establishments have increasingly been provided by existing businesses opening new locations. Those new locations have created jobs at a higher rate than brand-new firms, which helps to boost job creation. Looking at both forms of new establishments shows that job creation is down following the recession, but new locations were growing entering the recession and should be a critical component of job creation as the economy continues to recover.

The views authors express in Economic Commentary are theirs and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The series editor is Tasia Hane. This paper and its data are subject to revision; please visit clevelandfed.org for updates.

The rate at which Americans start new businesses has declined significantly over the past three-and-a-half decades, raising concerns among economists and policymakers about the state of American entrepreneurship.

The decline is troubling because new companies have historically played an important role in job creation—recent estimates put the number of new jobs created by new firms at 2.9 million annually on average (Haltiwanger et al. 2013).

But between 1978 and 2011, the formation rate for new firms with more than one employee dropped by more than one-third on a per capita basis, and the number of jobs created by new firms fell from 3.4 percent of total business employment to 2.0 percent. Moreover, these changes have occurred across all broad industry sectors and nearly all geographic locations (Decker et al., 2014; Hathaway and Litan, 2014).

But discussions about the engines of job growth may be too narrowly focused on new firms. After all, a brand-new company is not the only type of new business establishment that can be formed. When Walmart opens up a new store, Honda builds a new auto plant, or a local sports bar opens a second location across town, new establishments are formed and new jobs are created. And though these new business locations are included in the official new-establishment statistics, researchers frequently sift them out in order to focus only on brand-new firms when they investigate the drivers of job growth.

We analyzed the Census Bureau’s Business Dynamics Statistics database to explore recent trends in this neglected subset of new establishments and to gain insight into the declining trend in new business formation. We find that while new firms have been forming at a slower pace over the past 33 years and creating fewer jobs, there has been a simultaneous rise in the number of new establishments opened by existing businesses (which we will call new outlets). As the rate of new outlet formation has risen, so has the rate of job creation at new outlets.

Taken together, the declining rate of new firm formation and the rising rate of new outlet formation represent a shift in the source of new establishment formation and new job creation. Markets that used to be served by independent entrepreneurs creating businesses are now increasingly being served by the expansion of existing businesses.

Recent Trends in Establishment Formation Rates

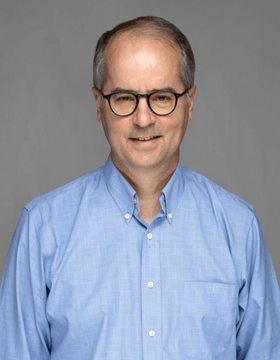

Figure 1 shows the annual formation rates of new firms with more than one employee and of new outlets. To allow direct comparison of new firm and outlet growth, we divide both the number of new firms opened in a year and the number of new outlets opened in a year by the total number of business establishments.1

Note: Shaded bars indicate recessions.

Source: Created from data from the U.S. Census Bureau, Business Dynamics Statistics.

As the figure shows, in 1978, Americans created 12.0 new firms per business establishment. By 2011, the latest year data are available, they generated new firms at roughly half that rate—6.2 new firms per existing business establishment. By contrast, in 1978, Americans created 1.7 new outlets per existing establishment, while in 2011 they created 2.6—an increase of more than half.

As a result of the growth in outlet formation and the decline in new firm formation, the proportion of new establishments created by new firms has fallen significantly. The new firm share of new establishment creation declined from 80.4 percent in 1978 to 59.9 percent in 2011.

Job Creation

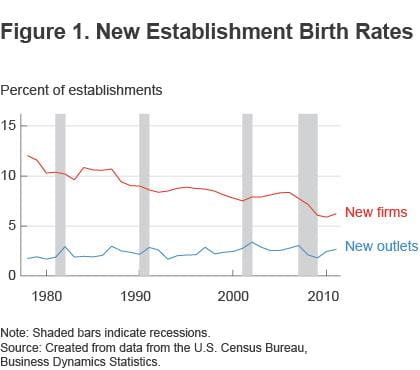

The number of new jobs created by new outlets has increased over time. Figure 2 shows the annual job creation rates of new firms and new outlets between 1978 and 2011. (We calculate the rates of each by dividing the number of employees at new firms or the number of employees at new outlets by the total number of employees in establishments. The sum of these two numbers equals the new establishment job creation rate.) Nonetheless, the increasing rate of new outlet formation does not offset the opposite trend in new firm formation, and the overall rate of new establishment formation is still declining.

Note: Shaded bars indicate recessions.

Source: Created from data from the U.S. Census Bureau, Business Dynamics Statistics.

As the figure shows, the rate of job creation from new firm formation has declined from 4.0 percent of employment in 1978 to 2.6 percent in 2007, while the rate of job creation from new outlet formation increased from 2.3 percent in 1978 to 2.9 percent in 2007. (Both new outlet and new firm job creation rates declined from 2007 to 2009 during the Great Recession and have since recovered slightly.)

It is important to note that neither the increase in job creation from new outlets, nor the decline in job creation from new firm formation comes from changes in the size of those establishments. Between 1978 and 2011, the average number of employees in a new outlet shrank from 21.48 to 13.90. Over the same period, the average number of employees per new firm increased from 5.40 employees in 1978 to 6.22 in 2011.

Job Creation by New Outlets

The data show that new firms and new outlets have created jobs at similar rates on average over the past 33 years. However, the trends for each over time are different. As Figure 2 shows, the share of job creation coming from new firms has been shrinking over time, whereas the share coming from new outlets had been increasing until the Great Recession.

To give a sense of the magnitude of the changing sources of job creation, we can estimate the number of new jobs that new firms would have created had they continued to generate jobs at the rate they did back in 1978 and the number of new jobs that new outlets would have created had they continued to generate jobs at the rate they did back in 1978. At the 1978 rate of new firm job creation, new firms would have produced an additional 2.4 million jobs in 2011, or 90 percent more. At the 1978 rate of new outlet job creation, new outlets would have produced 828,000 fewer jobs in 2011, or 34 percent less.

The Sectoral Composition of the Trend

Policymakers, journalists, and economists often allude to these job-creation trends when discussing the growth in multi-unit establishments that has occurred over the past 33 years. Often their examples come from the retail sector because most people can envision the replacement of mom-and-pop variety stores by Target, Old Navy, and similar outlets. Scholarly analysis has also documented this trend in the retail sector. Jarmin et al. (2005), for instance, provide large-sample statistical evidence that new outlets have replaced new firms in the retail sector.

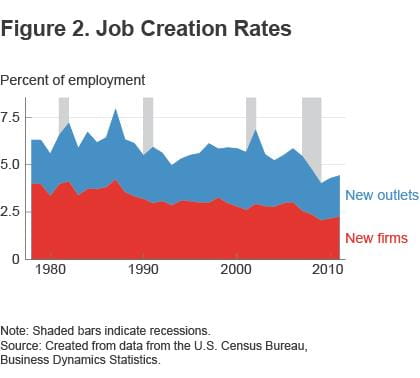

While the retail examples may be intuitive to most people, our examination of the Business Dynamics Statistics database shows that the shift away from new firm formation and job creation toward new outlet formation and job creation is widespread, and is, in fact, larger in industry sectors other than retail.

Figure 3 shows the new outlet share of new establishments in 1978 and 2011 by broad industry sector. The figure reveals that the rise in the new outlet share of establishments is not restricted to the retail sector. In all nine industry sectors, new outlets account for a larger fraction of establishments in 2011 than they did in 1978. Moreover, the size of the growth in the new outlet share of new establishments is larger in all of the other sectors than it is in retail.

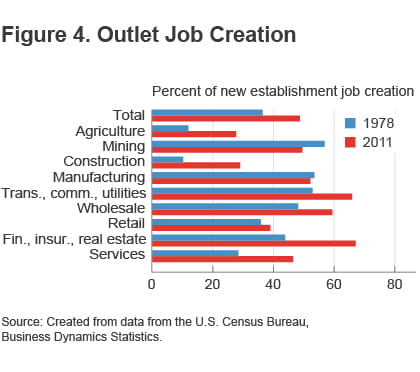

Figure 4 shows new outlet job creation as a share of new establishment job creation in 1978 and 2011 by broad industry sector. In seven of nine sectors, new outlets were responsible for a larger share of new establishment job creation in 2011 than they were in 1978. (Manufacturing and mining are the two exceptions.) Moreover, of the seven industries in which new outlet job creation rose as a share of new establishment job creation, the retail sector was the one with the smallest amount of growth in that measure.

Source: Created from data from the U.S. Census Bureau, Business Dynamics Statistics.

Source: Created from data from the U.S. Census Bureau, Business Dynamics Statistics.

Conclusion

As America has changed over the past three-plus decades, new establishments have been founded to serve changing markets. These new establishments and the jobs they generated could have been provided by entrepreneurs founding new firms or by the owners of existing businesses establishing new locations. The data show that they have increasingly been provided by existing businesses expanding into new locations.

While our analysis of the Business Dynamics Statistics data does not allow us to pinpoint any causes of this shift, we can offer one hypothesis: Growth in information and communication technologies since the late 1970s has facilitated the coordination of multiple establishments, offering existing businesses an advantage over new firms when setting up new establishments to meet the need for new business locations.

The decline in the rate of new firm formation and job creation by new firms may have occurred because the incentives for existing businesses to expand to new locations have grown. However, more research is needed before the cause of the decline in the rate of formation of new firms and its impact on the American economy can be more fully understood. Whatever the cause, the data indicate the growing importance of multi-establishment businesses to job creation.

Footnotes

- Technically, the denominator is the average of the number of business establishments in the current year and the prior year to account for regression to the mean (see Davis, et al. 1996). Return

References

- Davis, Steven J., John Haltiwanger, and Scott Schuh, 1996. Job Creation and Destruction. MIT Press.

- Decker, Ryan, John Haltiwanger, Ron S. Jarmin, and Javier Miranda, 2014. “The Secular Decline in Business Dynamism in the U.S.” University of Maryland working paper.

- Haltiwanger, John, Ron S. Jarmin, and Javier Miranda, 2013. “Who Creates Jobs? Small versus Large versus Young.” Review of Economics and Statistics, 95:2, 347-361

- Hathaway, Ian, and Robert E. Litan. 2014. “Declining Business Dynamism in the United States: A Look at States and Metros,” Brookings Institution, Economic Studies Paper.

- Jarmin, Ron S., Shawn D. Klimek, and Javier Miranda. 2005. “The Role of Retail Chains: National, Regional, and Industry Results,” CES working paper no. 05-30. Washington, D.C.: Center for Economic Studies, U.S. Census Bureau.

Suggested Citation

Hathaway, Ian, Mark E. Schweitzer, and Scott Shane. 2014. “The Shifting Source of New Business Establishments and New Jobs.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary 2014-15. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-ec-201415

This work by Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International