- Share

Short-Time Compensation: An Alternative to Layoffs during COVID-19

We discuss the costs and benefits of short-time compensation (STC), an unemployment insurance program that allows workers with temporarily reduced hours to receive some unemployment insurance benefits. We describe the provisions for STC in the Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012 and the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and report the utilization of STC before and after these acts. The number of states with STC programs has remained unchanged at 27 since the beginning of the pandemic, but STC utilization has recently risen to unprecedented levels, driven largely by increases in Michigan and Washington. However, these increases are small relative to increases in Germany’s popular Kurzarbeit program, suggesting that the United States’ STC program may still have scope for expansion.

The views authors express in Economic Commentary are theirs and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The series editor is Tasia Hane. This paper and its data are subject to revision; please visit clevelandfed.org for updates.

Since March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic and the efforts to contain its spread have strained the US labor market. The official unemployment rate fell to 7.9 percent in September but remains considerably above levels prior to the pandemic (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2020b). Many unemployed individuals, however, expect to return to their previous jobs. For example, about 35 percent of unemployed workers were on temporary layoff in September, compared to only about 15 percent in February (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2020a).1

Avoiding such temporary layoffs is one of the objectives of short-time compensation (STC) programs. STC allows firms to reduce workers’ hours temporarily instead of laying them off because the affected workers receive some unemployment insurance benefits from the STC program while their hours are reduced.

In this Economic Commentary, we discuss the costs and benefits of STC. We compare recent provisions for state STC programs in the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to provisions in the Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation (Jobs) Act of 2012. We find that STC utilization has risen to unprecedented levels since the passage of the CARES Act, driven largely by increases in Michigan and Washington. But the number of states with STC programs has remained unchanged at 27 since the beginning of the pandemic. And the recent increase in STC utilization is small relative to the utilization of other STC programs, such as Germany’s popular Kurzarbeit program, suggesting some scope for expansion.

What Is STC?

STC, also known as work sharing or shared work, is a type of unemployment insurance (UI) program that allows firms to reduce temporarily the hours of workers in lieu of laying workers off. Workers whose hours are reduced become eligible for unemployment benefits commensurate with the reduction of their hours (Department of Labor, 2019b). Like other UI programs, STC is administered by states and overseen by the US Department of Labor. Each state chooses whether it will offer an STC program. In states with STC programs, employers with a reduction in production, services, or other conditions may submit an STC plan to state authorities if employers meet four federal requirements, though individual states can make these requirements more stringent. Federal requirements for STC eligibility are described in Department of Labor (2016b). Once the state approves the employer’s STC plan, affected workers can receive STC benefits.

As an example, suppose an employer wants to lay off 20 of its 100 workers because of reduced demand for its products or services. If instead the firm reduces the workweek for all workers from five days to four (a 20 percent reduction in hours), it could propose an STC plan to the state. If the plan is approved, workers who make $500 per week and who would, if they were laid off, receive a weekly unemployment benefit amount of $200 per week (under a standard 40 percent replacement rate) would qualify for $40 per week (20 percent of $200) under the STC program. Workers would then work four days a week and earn $420 ($400 of earned wages and $20 of STC) instead of being laid off and receiving only $200.

The Benefits and Costs of STC

Microeconomic studies suggest that STC saves jobs, and macroeconomic studies using cross-country data typically find a positive effect of STC on aggregate employment (Boeri and Bruecker, 2011; Cahuc and Carcillo, 2011; Hijzen and Martin, 2013). Using microeconomic data, Cahuc, Kramarz, and Nevoux (2018) find that STC prevents inefficient job destruction and firm failure among firms that face large temporary declines in revenue and that have limited access to credit. Moreover, STC is a less costly way of saving jobs than wage or hiring subsidies because STC targets the most vulnerable jobs.

Other benefits include reducing the costs that accompany job loss, reducing hiring and firing costs, and allowing firms to retain skilled workers. There exists overwhelming evidence that permanent job losses result in large earnings and health costs (Jacobson, Lalonde, and Sullivan, 1993; Sullivan and von Wachter, 2009; Carrington and Fallick, 2017) and that these costs are more pronounced during recessions (Davis and von Wachter, 2011). Because STC programs reduce layoffs, they help some workers avoid the consequences of permanent job losses. STC programs also reduce employers’ unemployment taxes because fewer workers lose their jobs. STC programs may also promote faster economic recovery because firms avoid the costs of hiring and training new workers and they can easily increase existing employees’ hours as demand recovers. Finally, STC programs spread the burden of an economic downturn among many workers instead of concentrating it among a few who lose their jobs.

The costs of STC include possible labor market inefficiencies and several firm-level costs. First, STC may hinder the reallocation of workers from contracting firms to expanding firms (Cahuc, 2019). For example, concerns about face-to-face interactions during COVID-19 have led to a substantial increase in the demand for online grocery shopping and delivery services. To meet this growing demand, some retailers have hired new staff, reconfigured stores, and invested in new technologies, while other retailers have done little. As such, the large shift in shopping habits implies a reallocation of jobs and workers across firms (Barrero, Bloom, and Davis, 2020). To the extent that STC programs dampen this response, they reduce labor market productivity. This disadvantage is limited, however, because there are limits on the length of time that STC plans are in effect, usually no more than 12 months. Second, a reduction in hours may induce a firm’s best workers to quit, though this is a less serious concern if there is a deep reduction in aggregate demand and overall hiring is depressed.2 Third, STC can be more expensive to employers than layoffs primarily because STC claimants retain their health and retirement benefits. Finally, STC participation entails a high administrative burden for employers (Abraham and Houseman, 2014b).

STC Provisions of the 2012 Jobs and 2020 CARES Acts

The Jobs and CARES Acts had three similar provisions for state STC programs, although the Jobs Act was somewhat more generous. First, both acts specify that the federal government will cover 100 percent of STC benefit costs for states with existing programs. This provision lasted through the end of fiscal year 2015 for the Jobs Act and will last through the end of 2020 for the CARES Act. Second, the CARES Act allows states without STC programs to operate a temporary STC program administered by the federal government through the end of 2020, while the Jobs Act allowed states to participate in such a program for two years. Each act provides $100 million in grants for STC program development, administration, and promotion (Department of Labor, 2016b; Department of Labor, 2020a).

Recent Increases in STC Utilization

STC utilization is calculated as the percentage of initial UI claims that are STC claims, or, more precisely, “STC full-time equivalent claims.” STC full-time equivalent claims are a measure of the reduction in hours relative to full-time work. For example, if 100 workers have their hours reduced by 10 hours a week, going from 40 hours to 30 hours, the STC claims for those 100 workers will be represented as 25 STC full-time equivalent claims (100×10/40). Based on those 100 workers, STC utilization would be 25 divided by all UI claims for that week.3

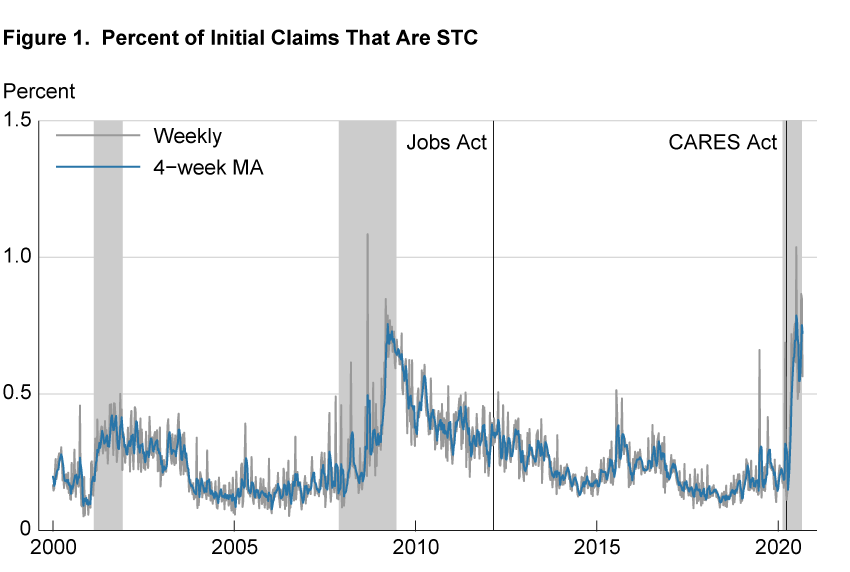

STC utilization has risen sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, STC utilization rose from about 0.2 percent before the pandemic to almost 0.8 percent in the week ending July 4, 2020, as shown in figure 1. This is the highest level of STC utilization during the last 20 years. In the week ending September 5, STC utilization remained elevated at above 0.7 percent.

Notes: STC claims are measured as full-time equivalent (see box 1 for the definition). Shaded bars indicate NBER recessions. Last observation: 9/5/2020.

Source: US Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration.

The recent increase in STC utilization likely represents the strong countercyclicality of STC utilization and not a response to the incentives for STC programs in the CARES Act, which went into effect on March 27, 2020. There are two reasons for this conclusion. First, STC utilization is strongly countercyclical—rising in recessions and falling in expansions—so we would expect it to rise during the current recession, regardless of legislative provisions. For example, STC utilization rose from about 0.1 percent during the 2000s expansion to about 0.8 percent at the height of the 2009 recession (comparable to the most recent increases) without legislative incentives for STC programs. Second, STC utilization stayed relatively flat at about 0.4 percent before and after the Jobs Act went into effect on February 22, 2012. This steadiness in STC utilization suggests that the incentives in the Jobs Act did not materially increase the use of STC. Because the provisions for STC in the Jobs Act were more generous than in the CARES Act, this evidence also suggests that the CARES Act is likely not responsible for the recent increase in STC utilization.

Box 1. Calculating STC Full-Time Equivalent Unemployment Claims

STC full-time equivalent claims measure a partial reduction in workers’ hours relative to full-time work. Here is an example:

- 100 workers, working 40 hours a week

- Lose 10 hours of work per week, going to 30 hours

- The STC full-time equivalent claims for those workers are calculated as:

- 100 × 10 ÷ 40 = 25

Then, to calculate STC utilization, we divide those 25 full-time equivalent claims by all initial unemployment insurance claims for that week.

Understanding the Recent Increases in STC Utilization:

Intensive versus Extensive Margins

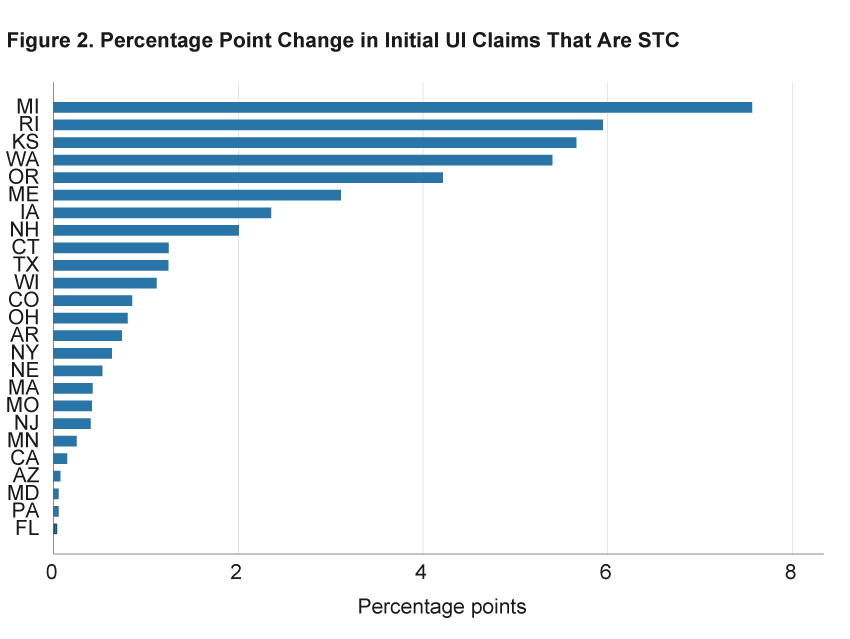

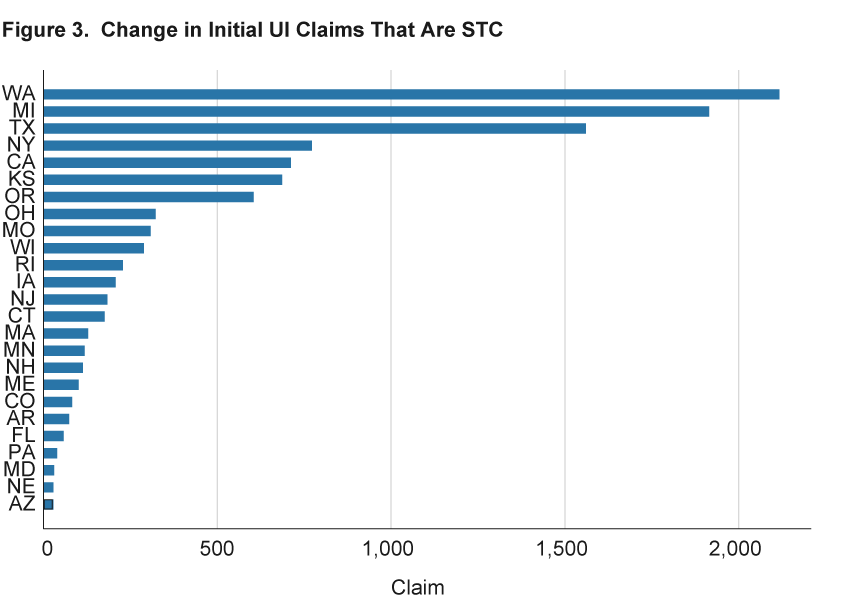

A couple of states with existing STC programs (the intensive margin) have driven the recent increase in national STC utilization. Figures 2 and 3 show the change in STC utilization rates and levels, respectively, between the week ending February 29, 2020—just prior to the pandemic—and the week ending July 4, 2020, when national STC utilization peaked. Michigan and Washington experienced particularly large increases in STC utilization rates and levels. For example, STC utilization has increased by more than 7 percent in Michigan, and Michigan’s weekly number of STC full-time equivalent claims has risen by almost 2,000. The level of STC claims has also risen considerably in Texas, despite only a moderate increase in the rate of STC utilization, because of relatively high initial UI claim levels.

Notes: This figure depicts the change in the 4-week moving average from 2/29/2020 to 7/4/2020. The figure includes states with positive STC utilization. States with no STC utilization do not have STC programs or are not utilizing them. STC claims are measured as full-time equivalent (see box 1 for the definition).

Source: US Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration.

Notes: This figure depicts the change in the 4-week moving average from 2/29/2020 to 7/4/2020. The figure includes states with positive STC utilization. States with no STC utilization do not have STC programs or are not utilizing them. STC claims are measured as full-time equivalent (see box 1 for the definition).

Source: US Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration.

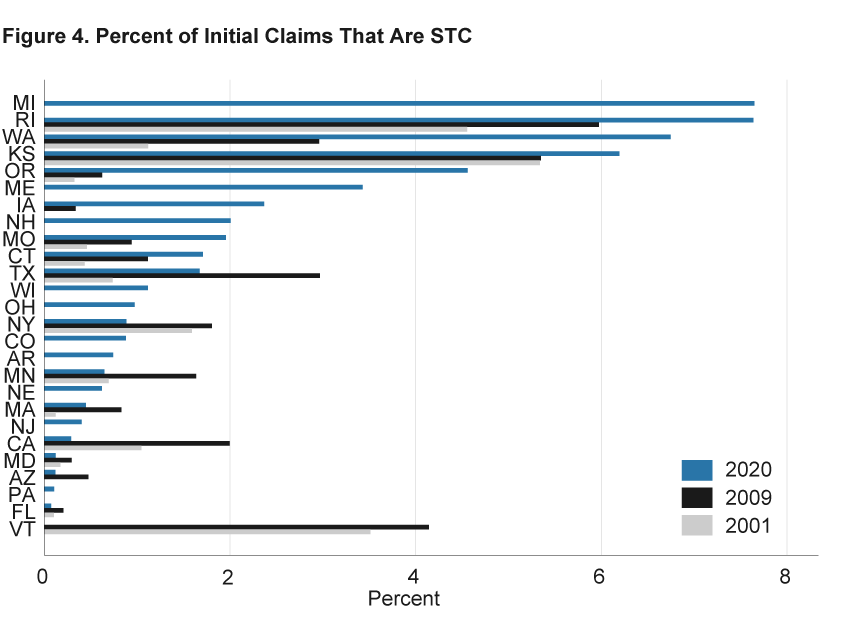

Washington, along with Rhode Island and Kansas, have had high STC utilization rates during the last three recessions, but high utilization in Michigan is a recent development. There are large differences in STC utilization across states during the current crisis and the previous two recessions, as shown in figure 4. For example, in the week ending July 4, 2020, STC utilization ranged from below 0.2 percent in Florida and Pennsylvania to above 6.0 percent in Kansas, Michigan, Rhode Island, and Washington. Most states have had utilization rates below 3.0 percent during the current crisis. During past recessions, state STC utilization rates were typically lower than during the current crisis, and Kansas, Rhode Island, and Washington have had consistently high utilization rates relative to those of other states. Employers in Michigan did not utilize STC in the last two recessions because the state had at that point no STC program.

Notes: 4-week moving average. We have chosen the week to correspond to the week with the highest STC utilization during each recession, that is, the week ending 8/18/2001 for the 2001 recession, the week ending 3/28/2009 for the 2009 recession, and the week ending 7/4/2020 for the current recession. The figure includes states with positive STC utilization in 2001, 2009, or 2020. States with no STC utilization do not have STC programs or are not utilizing them. STC claims are measured as full-time equivalent (see box 1 for the definition).

Source: US Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration.

Effective promotion of STC programs may explain why STC utilization has increased so much in Michigan and Washington, consistent with reporting in Cohen (2020). Knowledge of STC programs among employers in the United States is generally low, preventing widespread use (Shelton, 2011; Abraham and Houseman, 2014a; von Wachter, 2020). However, Michigan and Washington have promoted the use of work sharing during the COVID-19 pandemic.4 Additionally, Michigan relaxed its STC program eligibility requirements in several ways on April 22, 2020.5

The number of states with STC programs (the extensive margin) has not changed since the beginning of the pandemic. As of January 1, 2019, the District of Columbia (DC) and 27 states had STC programs (Department of Labor, 2019a). Since the pandemic began, only Virginia has authorized a new STC program, which will become active by January 1, 2021; Vermont inactivated its STC program on July 1, 2020 (National Governors Association, 2020).

The lack of new state STC programs following the 2020 CARES Act contrasts with the increases in new STC programs following the 2012 Jobs Act. In particular, before the 2012 Jobs Act, only 23 states and DC had STC programs in place (Department of Labor, 2012). But, by January 1, 2016, shortly after the STC provisions in the act expired, there were 28 states (plus DC) with STC programs (Department of Labor, 2016a). Thus, the Jobs Act may have prompted more states to put work-share programs in place; however, this implementation happened over several years following the passage of the act. The short durations of STC provisions in the CARES Act have presently been insufficient to induce widespread introduction of new STC programs.

The German Kurzarbeit Program

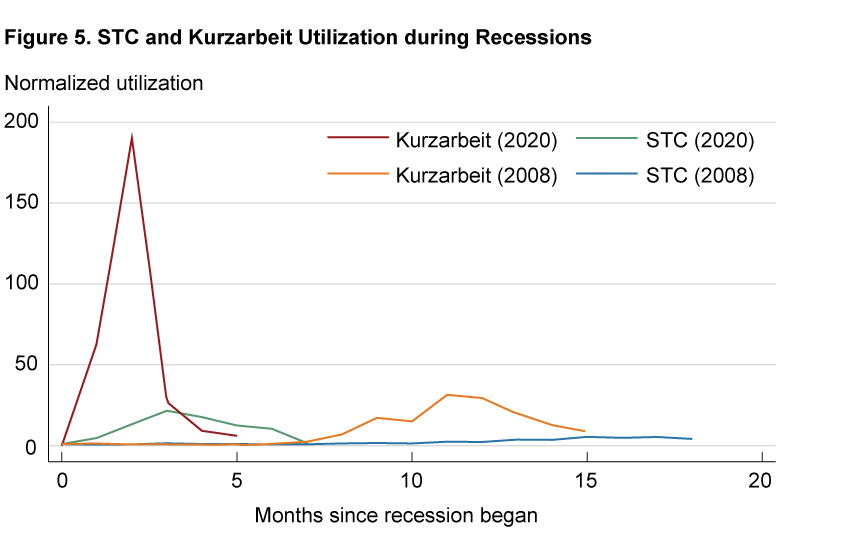

Many other developed countries have STC programs that have worked successfully in the past, but these programs typically have higher take-up rates and larger increases in utilization during economic downturns than those in the United States. In particular, Germany’s STC program—Kurzarbeit—is especially popular and well-established. For example, during the global financial crisis in 2009, about 3.2 percent of all German workers were on work-sharing plans through Kurzarbeit compared with only 0.2 percent of US workers in states with STC programs (Abraham and Houseman, 2014a). Recently, the German unemployment rate has also increased sharply, but increases in the number of workers affected by Kurzarbeit have been much larger than increases in STC claims in the United States (figure 5). In particular, Kurzarbeit applications increased sharply at the beginning of the current recession and rose almost 200 fold.6 US STC claims also rose, but the increases have been much smaller. During the previous recession, STC utilization also rose more in Germany than in the United States, and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development estimates that Kurzarbeit lowered unemployment by about 400,000 persons (1 percent of the labor force; OECD, 2009). Studies of Kurzarbeit could inform how expanded STC utilization might affect the US labor market.

Note: The 2008 recession began in December 2007 in the United States and in March 2008 in Germany. The 2020 recession is measured from February 2020 for both countries. STC and Kurzarbeit use is normalized to the first month of each recession. STC utilization in the United States is measured as the number of initial STC claims, which corresponds more closely to the measure in the German data. The German data give the number of workers affected by Kurzarbeit applications by employers. Germany had processing capacity constraints in March, so some notifications processed in April were filed in March.

Sources: US Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration; Bundesagentur für Arbeit (Germany).

Conclusion

The STC program encourages employers to reduce temporarily workers’ hours in lieu of layoffs. STC programs support employment, mitigate the consequences of permanent job loss, reduce employers’ unemployment insurance contributions, and spread out the burden of an economic downturn, although they might also dampen economic adjustment.

Both the Jobs and CARES Acts encouraged STC utilization, but evidence suggests that the recent increase in STC utilization is more likely the result of the recession rather than incentives in the CARES Act. In addition, the number of states with STC programs remains unchanged since the beginning of the pandemic, and the national increase in STC utilization was largely driven by two states, Michigan and Washington. Germany’s Kurzarbeit program, a work-share program that is used more extensively than STC in the United States and appears to have helped lower unemployment during recessions, may be useful for understanding the impact of expanded STC utilization in the United States.

Footnotes

- Kudlyak and Wolcott (2020) also document the prevalence of temporary layoffs during the current crisis using notices filed under the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification (WARN) Act. Krolikowski and Lunsford (2020) describe these data in more detail. Return

- After a sharp reduction in March and April, job vacancies have risen again, so this may be of concern. See: Job Openings, Total Nonfarm at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/JTSJOL. Return

- We also use STC full-time equivalent claims when calculating all initial UI claims. Return

- For example, Washington’s school districts and Michigan’s local governments have been encouraged to use STC programs (Inslee, 2020, and Michigan Department of Treasury, 2020, respectively). Return

- See Executive Order 2020-57: https://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2019-2020/executiveorder/pdf/2020-EO-57.pdf. Note that the provisions in this order have been extended by Executive Order 2020-76. Return

- Like the US STC program, Germany’s Kurzarbeit has a variety of eligibility parameters, many of which have been relaxed during the current recession. Notably, hours reduction requirements have been eased, pay replacement rates for time not worked have been increased (60 percent for the first three months of Kurzarbeit, 70 percent for the next three months, and 80 percent thereafter), the maximum duration of Kurzarbeit plans has been lengthened, and firms’ social security contributions have been waived (International Monetary Fund, 2020). Return

References

- Abraham, Katherine G., and Susan N. Houseman. 2014a. “Short-Time Compensation as a Tool to Mitigate Job Loss? Evidence on the US Experience during the Recent Recession.” Industrial Relations, 53(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/irel.12069.

- Abraham, Katherine G., and Susan N. Houseman. 2014b. “Encouraging Work Sharing to Reduce Unemployment.” https://www.hamiltonproject.org/papers/encourage_work_sharing_to_reduce_unemployment.

- Boeri, Tito, and Herbert Bruecker. 2011. “Short-Time Work Benefits Revisited: Some Lessons from the Great Recession.” Economic Policy, 26(68): 697–765. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0327.2011.271.x.

- Barrero, Jose Maria, Nick Bloom, and Steve J. Davis. 2020. “COVID-19 Is Also a Reallocation Shock.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (forthcoming). https://stevenjdavis.com/#whats-new.

- Cahuc, Pierre. 2019. “Short-Time Work Compensation Schemes and Employment.” IZA World of Labor. https://doi.org/10.15185/izawol.11.v2.

- Cahuc, Pierre, and Stéphane Cacillo. 2011. “Is Short-Time Work a Good Method to Keep Unemployment Down?” Nordic Economic Policy Review, 1(1): 133–165. https://doi.org/10.6027/9789289330541-9-en.

- Cahuc, Pierre, Francis Kramarz, and Sandra Nevoux. 2018. “When Short-Time Work Works.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 11673. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3247486.

- Carrington, William, and Bruce Fallick. 2017. “Why Do Earnings Fall with Job Displacement?” Industrial Relations, 56(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/irel.12192.

- Cohen, Patricia. 2020. “This Plan Pays to Avoid Layoffs. Why Don’t More Employers Use It?” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/20/business/economy/jobs-work-sharing-unemployment.html.

- Davis, Steven J., and Till von Wachter. 2011. “Recessions and the Costs of Job Loss.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2011 (2). https://muse.jhu.edu/article/475017.

- Department of Labor. 2012. “Comparison of State Unemployment Laws.” https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/comparison/2010-2019/comparison2012.asp.

- Department of Labor. 2016a. “Comparison of State Unemployment Laws.” https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/comparison/2010-2019/comparison2016.asp.

- Department of Labor. 2016b. “Implementation of the Short-Time Compensation (STC) Program Provisions in the Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012.” https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/docs/stc_report.pdf.

- Department of Labor. 2019a. “Comparison of State Unemployment Laws.” https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/comparison/2010-2019/comparison2019.asp.

- Department of Labor. 2019b. “Short-Time Compensation.” https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/docs/stc_fact_sheet.pdf.

- Department of Labor. 2020. “Unemployment Insurance Program Letter No. 21-20.” https://wdr.doleta.gov/directives/attach/UIPL/UIPL_21-20.pdf.

- Department of Labor, 2020b. “UI Replacement Rates Report.” Accessed September 15, 2020. https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/ui_replacement_rates.asp.

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. 2020a. “Table A-11. Unemployed Persons by Reason for Unemployment: Monthly, Seasonally Adjusted.” FRED. Accessed September 9, 2020. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/release/tables?rid=50&eid=3077.

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. 2020b. “Unemployment Rate.” FRED. Accessed September 9, 2020. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE.

- Hijzen, Alexander, and Sebastien Martin. 2013. “The Role of Short-Time Work Schemes during the Global Financial Crisis and Early Recovery: A Cross-Country Analysis.” IZA Journal of Labor Policy, 2:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-9004-2-5.

- Inslee, Jay. 2020. “Inslee Issues Two Public Education-Related Proclamations.” https://www.governor.wa.gov/news-media/inslee-issues-two-public-education-related-proclamations.

- International Monetary Fund. 2020. “Kurzarbeit: Germany’s Short-Time Work Benefit.” https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/06/11/na061120-kurzarbeit-germanys-short-time-work-benefit.

- Jacobson, Louis S., Robert J. Lalonde, and Daniel G. Sullivan. 1993. “Earnings Losses of Displaced Workers.” American Economic Review, 83(4). https://www.jstor.org/stable/2117574.

- Krolikowski, Pawel M., and Kurt G. Lunsford. 2020. “Advance Layoff Notices and Labor Market Forecasting.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Working Paper No. 20-03. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-wp-202003.

- Kudlyak, Marianna, and Erin Wolcott. 2020. “Pandemic Layoffs.” Unpublished manuscript. https://sites.google.com/site/erinwolcott/research.

- Michigan Department of Treasury. 2020. “Work Share Program Information.” https://www.michigan.gov/documents/treasury/Work_Share_Program_Information_692517_7.pdf.

- National Governors Association. 2020. “Short-Time Compensation Programs As a COVID-19 Response and Recovery Strategy.” https://www.nga.org/memos/short-term-compensation-programs-covid-19/.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development). 2009. “Employment Outlook—How Does Germany Compare?”

- Shelton, Alison. 2011. Compensated Work Sharing Arrangements (Short-Time Compensation) As an Alternative to Layoffs. Congressional Research Service Report 40689, Washington, DC. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R40689.

- Sullivan, Daniel, and Till von Wachter. 2009. “Job Displacement and Mortality: An Analysis Using Administrative Data.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(3). https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2009.124.3.1265.

- Von Wachter, Till. 2020. “The Long-Term Effects of the COVID-19 Crisis on Workers: How Scaling Up the Workforce System Can Help.” http://www.econ.ucla.edu/tvwachter/covid19/LT_effects_STC_memo_vonWachter.pdf.

Suggested Citation

Krolikowski, Pawel M., and Anna Weixel. 2020. “Short-Time Compensation: An Alternative to Layoffs during COVID-19.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary 2020-26. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-ec-202026

This work by Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International