- Share

Paper Money and Inflation in Colonial America

Inflation is often thought to be the result of excessive money creation—too many dollars chasing too few goods. While in principle this is true, in practice there can be a lot of leeway, so long as trust in the monetary authority’s ability to keep things under control remains high. The American colonists’ experience with paper money illustrates how and why this is so and offers lessons for the modern day.

The views authors express in Economic Commentary are theirs and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The series editor is Tasia Hane. This paper and its data are subject to revision; please visit clevelandfed.org for updates.

Money is a societal invention that reduces the costs of engaging in economic exchange. By so doing, money allows individuals to specialize in what they do best, and specialization—as Adam Smith famously pointed out—increases a nation’s standard of living. Absent money, we would all have to barter, which is time consuming and wasteful.

If money is to do its job well, it must maintain a stable value in terms of the goods and services that it buys. Traditionally, monies have kept their purchasing power by being made of precious metals—notably gold, silver, and copper—that had value outside of their monetary role. Today’s money is fiat; it has no intrinsic value. Precious metals do not back it, and its use stems only from people’s trust that governments and central banks will not undermine its purchasing power. The American colonies’ experiences with paper currency show that such trust depended on two important factors: that colonial governments did not issue too much paper and that colonial governments maintained the fiscal backing behind the currency. Inflation in the colonies was not solely a problem of too much money chasing too few goods; it had a fiscal component. That’s a lesson worth recalling today.

The Usefulness of Money

Money reduces the cost of engaging in economic exchange primarily by solving the double-coincidence-of-wants problem. Under barter, if you have an item to trade, you must first find people who want it and then find one among them who has exactly what you desire. That is difficult enough, but suppose you needed that specific thing today and had nothing to exchange until later. Making things always requires access to the goods necessary for their production before the final good is ready, but pure barter requires that receipts and outlays occur at the same time. Money solves the double-coincidence-of-wants problem by being a general medium of exchange, and it allows one to decouple the timing of receipts and outlays by offering a means of deferred payment.

A lack of money plagued colonial America. The problem surfaced as soon as settlement reached a stage where agricultural households reaped surpluses, and a fledgling network of commercial activities—trade, processing, small-scale production—emerged. The mercantile policies of England kept the American colonies perpetually short of specie, the various silver and gold coins that served as money across the globe. Whatever specie the colonies acquired through their trade with the Caribbean and southern Europe was lost when they imported finished goods from England.

The supply of specie depended on the colonies’ balance-of-payments position, and since the colonies often ran deficits, colonists frequently complained about the absence of “money” (specie). This is not to say that specie did not circulate; it did, but apparently never in sufficient abundance.

Without the convenience of money, colonists resorted to many less-efficient methods of trading. Barter, of course, was common, particularly in rural areas, but individuals often had to accept goods that they did not particularly need or want only because they had no other way to complete a transaction. They accepted these goods hoping to pass them on in future trades. Some items, most famously tobacco in Virginia and Maryland, worked well in this way and became commodity monies directly or as backing for warehouse receipts. Various other types of warehouse receipts, bills of exchange against deposits in London, and individuals’ promissory notes might also circulate as money. In addition, shopkeepers and employers sometimes issued “shop notes,” a type of scrip—often in small denominations—redeemable at a specific store.

Out of necessity, merchants and wealthy individuals frequently extended credit to others. In an economy that depended heavily on barter, however, one could end up holding debts against many individuals and across a broad array of goods. People naturally hoped to net out some of these debts, but this is extremely difficult under barter. Fortunately, colonial creditors could tally debts in British pounds or colonial currencies even if these currencies were not readily available. In this way, money acted as a unit of account. By attaching a value to things, money accommodated the netting out of debts.

Colonial money first arose in the mid-seventeenth century as a unit of account for just such purposes. Moreover, to attract much-needed specie into the colonies, merchants bid the prices of the various silver and gold coins above their official British pound prices, as set by the British mint. These colonial premiums could be quite substantial. A silver coin might be worth more Massachusetts pounds than Pennsylvania pounds. In this way, the different premiums for specie defined distinct colonial money—even though no specific colonial currency actually circulated.

Money, acting as a unit of account, ideally describes the value of various goods and services, but money does not determine their values. That results from an interaction of both the costs of producing something and the public’s desire to possess it. But this explanation is a bit shallow. How are the costs of producing something or the desire to possess it “valued” independent of the monetary units—in this case, colonial pounds—used to describe them? Ultimately what people are willing to give up to produce or to possess an item determines its value. This naturally reflects the next best use of the materials employed to make the item, the next best use of producers’ talents and time, and what the purchasers will give up to own it. Adjustments in the terms for which individuals will trade one good against its next best alternative ultimately balance choices and efforts and set the values of things. Whatever asset functions as money must accurately and persistently record this underlying value and convert the barter terms of trade into money prices. To do so accurately, money must maintain a stable purchasing power.

Fiat Money in America

Short on specie, the American colonies first turned to fiat paper money in the late seventeenth century. These paper currencies eventually came to make up the lion’s share of currency in colonialAmerica—estimated between 50 and 75 percent of the total, with specie making up nearly all of the rest.

In 1686, Massachusetts established the first American land bank. Others soon followed. Despite the name, these were not true banks; they did not accept deposits. Instead, they issued “banks” of notes, or “bills on loan,” to borrowers who put up land as collateral with the bank. To fortify confidence in the notes, colonial governments promised to issue only a fixed amount of notes for a set term and to secure their loans with collateral typically equal to twice the amount of the loan. These notes soon became legal tender for all private and public debts. Principal and interest payments were due annually, but the bank often delayed the first principal payment for a few years. Payments had to be made in notes or in specie. While the notes furnished a circulating currency, the interest payments provided a revenue stream to the colonial governments.

In 1690, Massachusetts inadvertently created a second type of fiat money, “bills on credit,” when the colony issued certificates—short-term government bonds—to finance an attack on Quebec during King William’s War (1689-1697). The colonial government intended to quickly redeem the certificates with tax revenues, but the need for money was so great that the certificates began changing hands, like money. The practice quickly caught on among the colonies as a means of supplying a circulating currency. The issuances were to be temporary, in fixed amounts, and accompanied by taxes and custom duties to redeem them.

To retire these bills on credit, the colonial governments accepted them—along with specie—in payment of taxes, fines, and fees. As with “bills on loan,” the governments used any specie that they received in tax payments to retire and then burn the notes. Also like “bills on loan,” the notes became legal tender for private debts. The notes circulated freely within the colonies that issued them and sometimes in adjacent colonies. New England, however, was an exception; because of their close economic interconnections, the notes of Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island circulated throughout New England to such an extent that they constituted a single money stock.

The Value of Fiat

In general, the paper-money issues of the American colonies successfully provided a fairly stable medium of exchange that encouraged commerce and economic growth, but this was not universally the case. In some colonies, inflation became a serious problem, and according to scholars, it was not simply a matter of too much money chasing too few goods. New England’s experience illustrates the problem.

Following its successful use of fiat money in 1690, Massachusetts made multiple issues of paper currency to finance its involvement in Queen Anne’s War (1702-1713). Over the next 10 years, the stock of paper currency in Massachusetts increased by an incredible 39 percent per year (compound annual rate). The other New England colonies also began issuing paper currencies to meet wartime and other expenses. Between 1703 and 1713, the quantity of paper currency circulating in New England had increased at least 34-fold. This sharp increase in the stock of paper currency, however, did not seem to have a correspondingly large inflationary kick. The price of silver in Boston, which measures the depreciation of the Massachusetts pound and proxies for inflation in New England, rose only from 7 shillings to 8½ shillings over the course of the war. According to historian Leslie Brock, this modest rise probably reflected a premium that merchants were willing to pay to acquire specie, rather than an underlying inflation. Specie, always in short supply, had begun to grow even scarcer during the war.

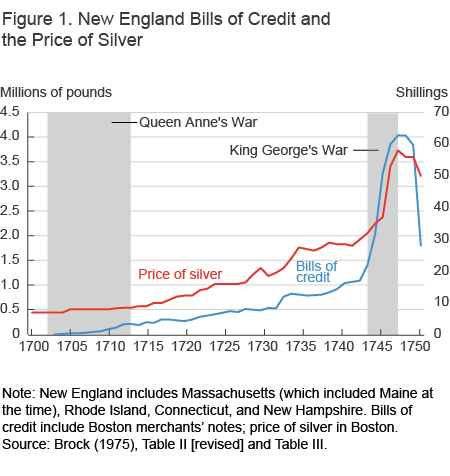

In part, the lack of inflation reflected the relationship between paper currency, which circulated only in New England, and specie, which circulated globally. When a colony issued paper currency, it tended to lose specie. The loss offset the fiat-money expansion and reduced the inflationary consequences of the paper-currency emission. The initial emission of paper money in Massachusetts during Queen Anne’s War, for example, seems to have had little effect on the price level because specie was draining out of the colony. By 1711, however, specie was becoming quite scare, and by the end of the decade, specie seems to have disappeared completely from New England. Without an offsetting outflow of specie, the relationship between the issuances of paper currency and inflation grew tighter, as figure 1 illustrates.

Note: New England includes Massachusetts (which included Maine at the time), Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire. Bills of credit include Boston merchants' notes; price of silver in boston.

Source: Brock (1975), Table II [revised] and Table III.

When Queen Anne’s War ended in 1714, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut reduced their stocks of paper currency for a time, but doing so depressed economic activity. This was a shortcoming of issuing specific amounts of fiat money for short periods of time. If the expansion of currency could lift economic activity, the contraction could depress it. In response, Massachusetts resumed its issuance. Between 1714 and 1743, Massachusetts’s paper currency stock increased a relatively modest 3.2 percent per year (compound annual rate). Over this same period Rhode Island increased its bills by a very substantial 12.5 percent per year, while Connecticut and New Hampshire increased theirs at about half that rate. Since the currency of one New England colony circulated among the others, the overall stock of paper currency in New England rose 5.5 percent per year. Over these years, Rhode Island—the second smallest colony—had issued, on balance, more currency than Massachusetts and substantially more than Connecticut and New Hampshire combined. The price of silver in Boston rose 4.3 percent per year, suggesting a substantial rate of inflation.

Inflation became a growing, pernicious problem in New England, but it exploded during King George’s War (1743-1748). To finance the conflict, New England’s colonies again resorted to huge issues of paper currency. Over these years, the stock of fiat money increased by 24.3 percent per year (compound annual rate). With specie no longer circulating in New England, inflation was the inevitable consequence. One scholar refers to this period as New England’s “great inflation.” During the war, the price of silver in Boston rose by a very sharp 11 percent per year.

In Massachusetts, the sharp rise in fiat money after 1720 is statistically correlated with the issuance of paper currency, but a similar correspondence does not seem to hold for the other American colonies. Robert West found no such relationship in Pennsylvania, New York, or North Carolina. Moreover, links between the issuance of fiat money and inflation seem absent in New England prior to 1720. The colonial American experience seems to suggest that while an excessive increase in the quantity of money is a necessary condition for inflation, it may not be sufficient.

Other economists contend that what mattered was not so much the quantity of fiat but the confidence that people placed in its backing. Although the colonies issued substantial amounts of paper money during the French and Indian War (1754-1763), inflation remained relatively subdued. The mortgage and tax payments through which colonial governments promised to cancel the notes backed the outstanding stock of paper currency.

Only when colonial governments mismanaged their paper, failed to tax sufficiently to retire their bills, or failed to pursue those delinquent on loan payments, would people grow reluctant to hold the currency and seek to convert it into tangible goods or specie. Inflation and depreciations followed. Inflation in the American colonies had a distinct fiscal edge: Paper-money issuances financed budget deficits, a situation that eventually drew a response from England.

Quantity and Quality

British authorities initially viewed colonial paper currency favorably because it supported trade with England, but following New England’s “great inflation” in the 1740s, this view changed. Parliament passed the Currency Act of 1751 to strictly limit the quantity of paper currency that could be issued in New England and to strengthen its fiscal backing. The Act required the colonies to retire all existing bills of credit on schedule. In the future, the colonies could, at most, issue fiat currencies equal to one year’s worth of government expenditures provided that they retired the bills within two years. During wars, colonies could issue larger amounts, provided that they backed all such issuances with taxes and compensated note holders for any losses in the real value of the notes, presumably by paying interest on them. As a further important constraint on the colonies’ monetary policies, Parliament prohibited New England from making any fiat currency legal tender for private transactions. In 1764, Parliament extended the Currency Act to all of the American colonies.

The Currency Act addressed both the quantity and the quality of colonial paper. Parliament understood that fiat money financed fiscal deficits and government debt and appreciated that both the quantity and the quality of the currency contributed to inflation. In an era of deficits and high public debt, it is lesson worth remembering.

References

- For a good introduction with useful references, see: Edwin J. Perkins, 1988. The Economy of Colonial America. New York: Columbia University Press.

- For a detailed discussion, see: Leslie V. Brock, 1975. The Currency of the American Colonies 1700 - 1764, A Study in Colonial Finance and Imperial Relations. New York: Arno Press.

- I referred to the empirical work in: Robert G. West, 1978. “Money in the Colonial American Economy,” Economic Inquiry, 16(1): 1-15. A longer version with detailed references is available from the author.

Suggested Citation

Humpage, Owen F. 2015. “Paper Money and Inflation in Colonial America.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary 2015-06. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-ec-201506

This work by Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International