- Share

The Employability of Returning Citizens is Key to Neighborhood Revitalization

One problem low-income communities may face in trying to revitalize is dealing with a high share of residents who are returning home after serving prison terms. Returning citizens often concentrate in low-income areas, and they typically lack the education and skills needed to find jobs. This Commentary reviews these and other barriers to employment, estimates the degree of unemployment, and describes some solutions emerging for this population.

The views authors express in Economic Commentary are theirs and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The series editor is Tasia Hane. This paper and its data are subject to revision; please visit clevelandfed.org for updates.

“The best antipoverty program,” the cliché goes, “is a good job.” But for people who have been in prison, jobs—let alone good ones—are hard to come by. (Note that agencies working to assist those who have served prison terms prefer to use the term “returning citizens” when referring to this population, a practice we will observe.)

Nobody really knows what the current unemployment rate is among returning citizens, but we do know that unemployment is extremely high in neighborhoods where returning citizens are concentrated. For example, in the Central, Hough, Glenville, Fairfax, and Mount Pleasant neighborhoods of Cleveland, which receive about 80 percent of the people released from prison in Cuyahoga County, the overall unemployment rate is 27 percent (37 percent in Central), according to the 2007–2011 American Community Survey (ACS). Among the lowest-income population, the group in which these citizens nearly always fall, the unemployment rate is 50 percent.

The employment challenges of returning citizens are an important economic development issue in many low-income communities throughout the country. In the five neighborhoods just mentioned, for example, approximately 37,000 people are in the labor force (37 percent of the population, excluding discouraged workers and those on disability) and 9,900 are unemployed, according to the ACS. Every year, approximately 3,000 citizens who complete their incarceration terms return to these neighborhoods, according to our community contacts and Ohio Department of Corrections data.

In other words, a population that is nearly 8 percent of the labor force is added every year to an already distressed labor market. If those who have served their time in prison are not job-ready when they are released, these distressed areas may continue to struggle.

The Problem

While no one knows for sure how many people in the U.S. have felony convictions, the number is surely significant. The U.S. Department of Justice notes that it can only estimate the number of people (currently living) who have served time in a state or federal prison.1 According to the most recent data (year-end 2001), that number was 1 in 37 U.S. adults, which amounted to more than 5.6 million individuals. The same ratio applied to our current population would imply 6.6 million adults.

The challenge for communities is not just that the numbers are large but that returning citizens are also concentrated in the poorest areas. Each year since 2007, for example, more than 720,000 inmates have been released nationwide from state and federal prisons, and around 5,000 to 7,000 of them have likely returned to the poorest neighborhoods of Cuyahoga County. Cleveland’s Central neighborhood, which has a population of approximately 12,000, is expected to absorb 500 to 600 of these newly released citizens every year, according to nonprofits operating in the area.

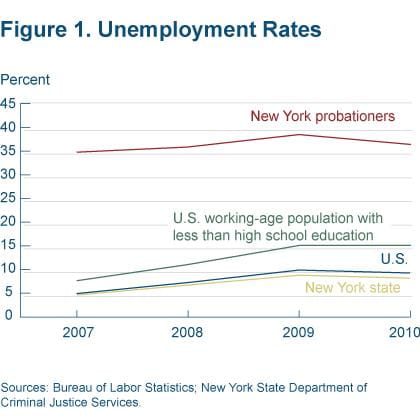

Achieving stable employment can be a daunting task for returning citizens, especially in a tough job market. Figure 1 illustrates the impact of crime on chances of employment. Because employment statistics for returning citizens are not available at the national level (nor at the local level in many states), the figure compares the unemployment rate of convicts on probation in New York State to the unemployment rate of U.S. residents with less than a high school diploma. People with criminal records are typically less-educated, so the less-educated population is a good comparison group for the returning citizen population. For example, 97 percent of convicts who went to prison from Cuyahoga County in 2010 had a high school diploma or less. (To the best of our knowledge, similar data is not available for New York.)

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics; New York State Department of Criminal Justice Services.

While the unemployment rate of the less-educated population was around 15 percent in 2010, 36 percent of New York probationers were looking for a job in the same year. Other estimates put the unemployment rate for returning citizens as high as 60 percent to 75 percent one year after release. Considering that in 2010, 40 percent of the general unemployed population has been looking for a job for more than 26 weeks—a post–World War II high—it is clear that people with a prison term on their resume are fighting an uphill battle.

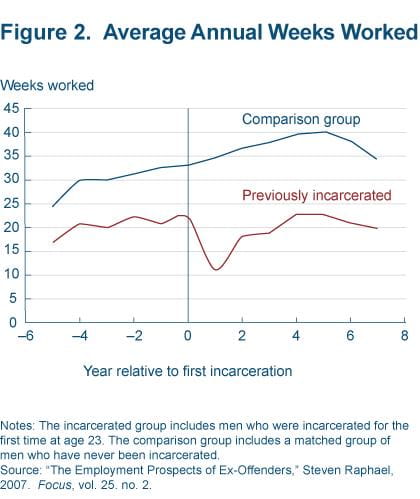

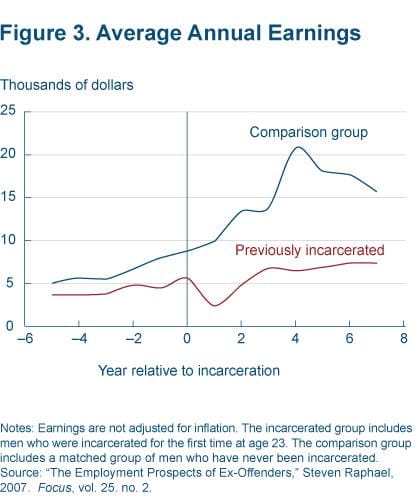

Even when they are employed, returning citizens work 9 to 11 fewer hours per week and earn less money per hour than the general population with similar skills and productivity (figures 2 and 3). They are also provided few chances for upward mobility, according to research done by Steven Raphael.

Notes: The incarcerated group includes men who were incarcerated for the first time at age 23. The comparison group includes a matched group of men who have never been incarcerated.

Source: "The Employment Prospects of Ex-Offenders," Steven Raphael, 2007. Focus, vol. 25. no. 2.

Notes: Earnings are not adjusted for inflation. The incarcerated group includes men who were incarcerated for the first time at age 23. The comparison group includes a matched group of men who have never been incarcerated.

Source: "The Employment Prospects of Ex-Offenders," Steven Raphael, 2007. Focus, vol. 25. no. 2.

Barriers to Gainful Employment

Returning citizens face many employment barriers. While the fear that a person with a criminal background could be violent or prone to repeat criminal activity might seem an obvious one, it is not a big concern for most employers. A far more significant barrier for returning citizens is that they lack the skills that are required in the labor market. The typical job candidate from this population lacks education, work experience, and soft skills like reliability and punctuality.

Surveys show that about 70 percent of offenders and returning citizens are high school dropouts and about half are functionally illiterate. Of those who had less than a GED upon admission to prison, only about 40 percent complete a GED while incarcerated.

Returning citizens often lack soft skills that employers look for, such as showing up to work every day and on time, working hard, being generally trustworthy, and having the necessary communication skills to interact with customers. Surveys of potential employers have shown that many employers are not necessarily worried about a repeat crime on their premises or being sued for having hired a returning citizen if something goes wrong. Rather, they are worried that returning citizens will not be good employees.

Many returning citizens also suffer from a lack of work experience. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, between 21 percent and 38 percent of prisoners were unemployed just prior to being incarcerated, depending on their level of educational attainment. Only between 57 percent and 76 percent of prisoners—mostly better-educated ones—reported receiving income from wages in the month prior to their arrest.

Work experience gained during incarceration seems to increase employment opportunities after release. Inmates involved in prison-employment programs are less likely to be rearrested upon release and more likely to obtain employment. Some studies suggest that corrections-based education, vocational, and work-program participants recidivate at a lower rate and are twice as likely to find employment after release than nonparticipants.

However, program-participation rates are extremely low; around 7 percent of inmates were assigned to industry jobs in state prisons in 2002, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.2 It is also not clear whether the skills gained during prison employment (such as garment assembly or license plate manufacturing) are still relevant in today’s economy. Thus, for the great majority, their already-low human capital continues to depreciate during incarceration.

Another factor that affects success rates in the job market is substance abuse and other physical and mental health problems. About three-fourths of incarcerated men have had substance abuse problems; close to 10 percent of state inmates are diagnosed with manic depression and bipolar disorder, and 4.6 percent with schizophrenia (comparable figures for the U.S. population are 2.6 percent and 1.1 percent respectively); 2–3 percent have AIDS or are HIV-positive; 18 percent have hepatitis C; and 15–20 percent report emotional disorders. Large numbers of female returning citizens suffer from depression and/or past sexual abuse. Both sexes tend to have low self-esteem, which may not only lead to or aggravate depression but also reduces job retention rates and avoidance of crime.

A final barrier to employability comes from so-called “collateral sanctions.” These are activities that returning citizens are banned from engaging in after their release. Until recently, hundreds of restricted activities in Ohio included obtaining a driver’s license, a real estate license, or a social worker license, operating a barber shop or a motorcycle training school, and working as a cosmetician, an athletic trainer, or an asbestos and contaminated property cleanup professional.

A recent bill in Ohio, signed into law in June 2012, lifts some of the restrictions on occupational licenses needed for jobs such as truck driver and barber. Still, across the country, states ban returning citizens from roughly 800 occupations. In some states, employers can fire their workers if they find out about past convictions, even if those convictions are old or are not relevant to current job responsibilities. In many states, employers are even allowed to consider arrests that did not lead to conviction. Any softening of collateral sanctions requires legislative action, which will ultimately be driven by a change in public perception.

Remedies for the Long Run

Returning citizens are up against significant employment challenges. But despite the many disadvantages they face in the labor market, studies have shown that there are interventions that may improve their labor market and life outcomes. Programs, such as the Transitional Jobs Program of New York City’s Center for Employment Opportunities, have shown that many returning citizens can and do find jobs and stay out of trouble when they are trained and properly motivated. Training and motivational intervention seems to matter most for the younger population, if it is administered soon after their release from prison.

Federal and state programs provide some support to businesses that consider employing a returning citizen. These incentives can provide returning citizens with the opportunity to build job and soft skills. The Federal Bonding Program of the U.S. Department of Labor protects employers for up to $5,000 from theft that may arise as a result of employing an individual with a criminal record. Some states, including Ohio, also have similar fidelity bond programs. The Work Opportunity Tax Credit provides employers with a $2,400 tax reduction if they hire a returning citizen.

Community groups have organized initiatives to generate employment opportunities for returning citizens. Evergreen Cooperatives in the Greater University Circle area of Cleveland is one example. The cooperative is a group of three employee-owned companies that hires locally in neighborhoods where the median income is less than $18,500. Community residents, including returning citizens, can start rebuilding their resumes while working in their own community. As an additional incentive, employees are given an equity stake in the company they are employed with, allowing them to build financial assets. Over the next three to five years, the cooperative hopes to expand its business lines to employ 500 individuals from the poorest six neighborhoods of the city, with a long-term goal to employ 5,000 Clevelanders in 10 to 15 years.3

Many more such programs and incentives will be needed. The more opportunities these citizens have to learn skills on the job, the more traction this population will have in the labor market. Coordination with existing programs to address some of the other barriers returning citizens face—such as low education, mental illness,or substance abuse—can improve outcomes as well. Given the high concentrations of returning citizens in some of the poorest neighborhoods, improving the employability of returning citizens could provide a needed boost to the economic conditions in these communities.

Footnotes

- “How many persons in the U.S. have ever been convicted of a felony?” Bureau of Justice Statistics website FAQ. Return

- Industrial jobs include garment assembly, furniture making, license plate manufacturing, metal fabrication, printing, agriculture, and janitorial labor. Return

- Evergreen Cooperatives website. Return

References

- “Disadvantaged Young Men and Crime,” Richard B. Freeman, 2000. In: David G. Blanchflower and Richard B. Freeman, eds., Youth Employment and Joblessness in Advanced Countries, NBER, University of Chicago Press.

- “The Employment Prospects of Ex-Offenders,” Steven Raphael, 2007. Focus, vol. 25. no. 2.

- “Improving Employment Prospects for Former Prison Inmates: Challenges and Policy,” Steven Raphael, 2010. NBER working paper, no. 15874.

- “More Than a Job: Final Results from the Evaluation of the Center for Employment Opportunities (CEO) Transitional Jobs Program,” Cindy Redcross, Megan Millenky, Timothy Rudd, and Valerie Levshin, 2011. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Report no. 2011-18.

- “Work As a Turning Point in the Life Course of Criminals: A Duration Model of Age, Employment, and Recidivism,” Christopher Uggen, 2000. American Sociological Review, vol. 67.

Suggested Citation

Ergungor, O. Emre, and Nelson Oliver. 2013. “The Employability of Returning Citizens is Key to Neighborhood Revitalization.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary 2013-17. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-ec-201317

This work by Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International