- Share

Strong Recovery for Whom? Trends in Dayton, Ohio, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Exemplify Growing Earnings Gaps between Minority and White Workers Present in Many US Regions

The gap in earnings between the typical white and minority worker grew in these two metro areas more than any other metro area during a 10-year period encompassing both the Great Recession and subsequent recovery. The reasons for the growing gap differ, reflecting divergent trends existent across the country.

The views expressed in this report are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Introduction and Background

Many topline indicators such as the number of jobs, average wages, and unemployment rates suggest that most people in the United States have recovered their economic position since the 2007 recession. Such suggestions may be true for the population on average, but they mask important, underlying trends experienced by certain races and in certain locations.1

We focus on two regions in particular—Dayton, Ohio, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—where the gap in earnings between the typical white and minority workers grew more than in any other metro area during a 10-year period encompassing both the Great Recession and subsequent recovery (2007 to 2017) despite more minorities working and employment gaps closing.2 We found the underlying data from Metro Monitor 2019 to be useful because it measures not only metropolitan-area growth (jobs, GDP, growth of young firms) and prosperity (earnings, productivity) over time, but it also provides rare measures of economic inclusion by annual earnings and by race.

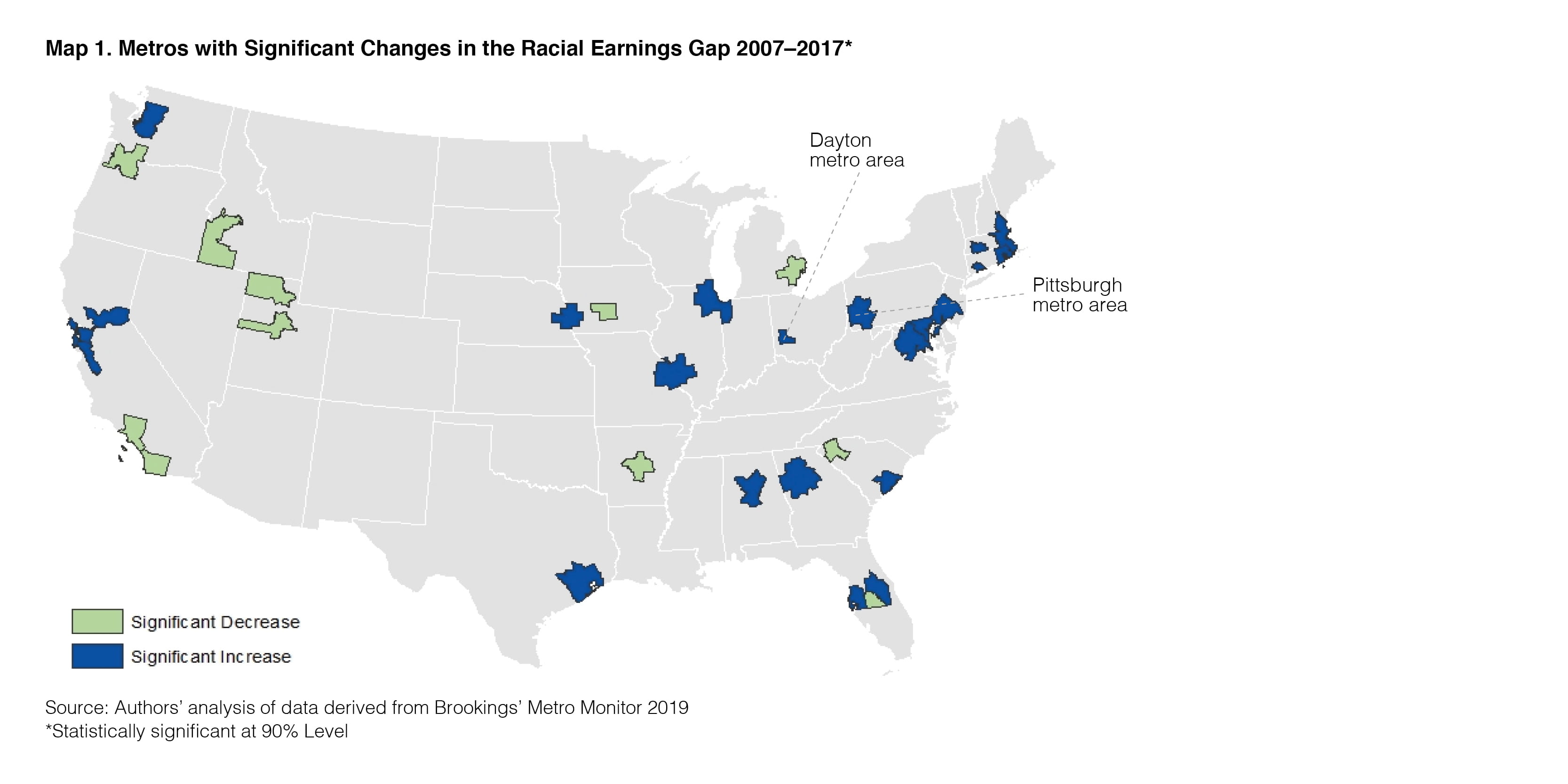

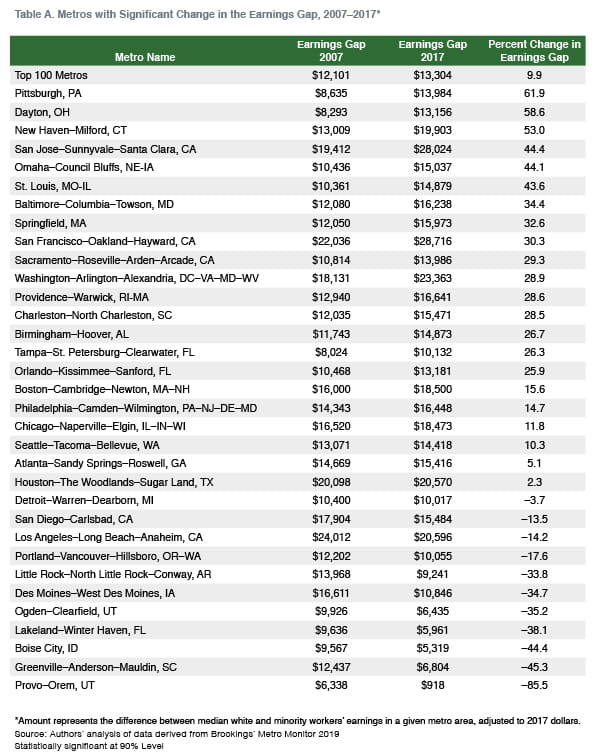

Dayton and Pittsburgh are 2 of 22 metro areas across the country that exhibited such racial earnings gap growth; 11 metro areas saw the racial gap in earnings close (see Map 1 and Appendix Table A). In addition to being of interest to the Cleveland Fed because they are two metros within the Federal Reserve’s Fourth District, Dayton and Pittsburgh help illustrate two different reasons for the growing racial earnings gap that reflect the divergent trends existent across the country.3

The earnings gap between white and minority workers is just one indicator of racial inequality, and it represents just one legacy of structural racism in the United States.4 But it is an important one. New research from the Cleveland Fed finds that income differences are an important driver of the persistence of the racial wealth gap, suggesting that narrowing the income gap would go a long way toward aiding the closing of the wealth gap.5

We acknowledge that earnings are not the whole story. Who enters the ranks of the employed, and when they enter, complicates the story of gains in earnings.6 For example, workers who had been previously unattached or marginally attached to the labor force (that is, neither working nor actively seeking work in the 12 months prior to each survey) and are brought into the workforce by a stronger economy may enter at a lower wage and thus bring down overall earnings of the group, minority or white. Given that minority workers in both Dayton and Pittsburgh—and nationally—outpaced their white counterparts in employment rate growth, this is an important factor to consider.7 Additionally, one might imagine that the recession may have caused retirements or layoffs of formerly blue-collar workers earning higher wages; later, these workers were replaced with workers at lower wages. Nevertheless, we focus on overall earnings trends in order to draw attention to the widening gap occurring in specific locations, and we encourage the continued monitoring of whether the earning gaps close over time. Some data show positive signs.8

Earnings Gaps in Dayton and Pittsburgh: An Overview

In the following paragraphs, we further discuss what may have influenced the earnings gap in both Dayton and Pittsburgh, how the gaps in the two metros differ, and the types of activities that local stakeholders are undertaking to address deep-seated racial inequities and the variation in economic outcomes by race.

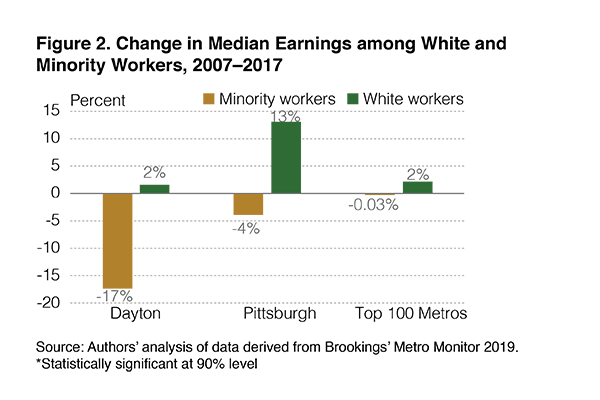

Historically, both Dayton and Pittsburgh have been challenged by declines in manufacturing jobs, loss of population, and the effects of the foreclosure crisis. Yet gaps in earnings between white and minority workers are evidence of how economic trajectories manifest differently. In Dayton, earnings declined for minority workers while white workers’ earnings remained stagnant. In Pittsburgh, earnings for minority workers remained stagnant while white workers’ earnings increased (Figures 1 and 2). These metro areas illustrate the complexity and range of economic trends across the country and are characteristic of a popular, dueling narrative: Some places are strengthening or attracting burgeoning, tech-related industries that tend to benefit higher-educated white workers (Pittsburgh), while others struggle to identify their niche in a transitioning economy and remain stuck trying to replace middle-wage legacy industries, important to many minority communities, with lower-paying jobs (Dayton).

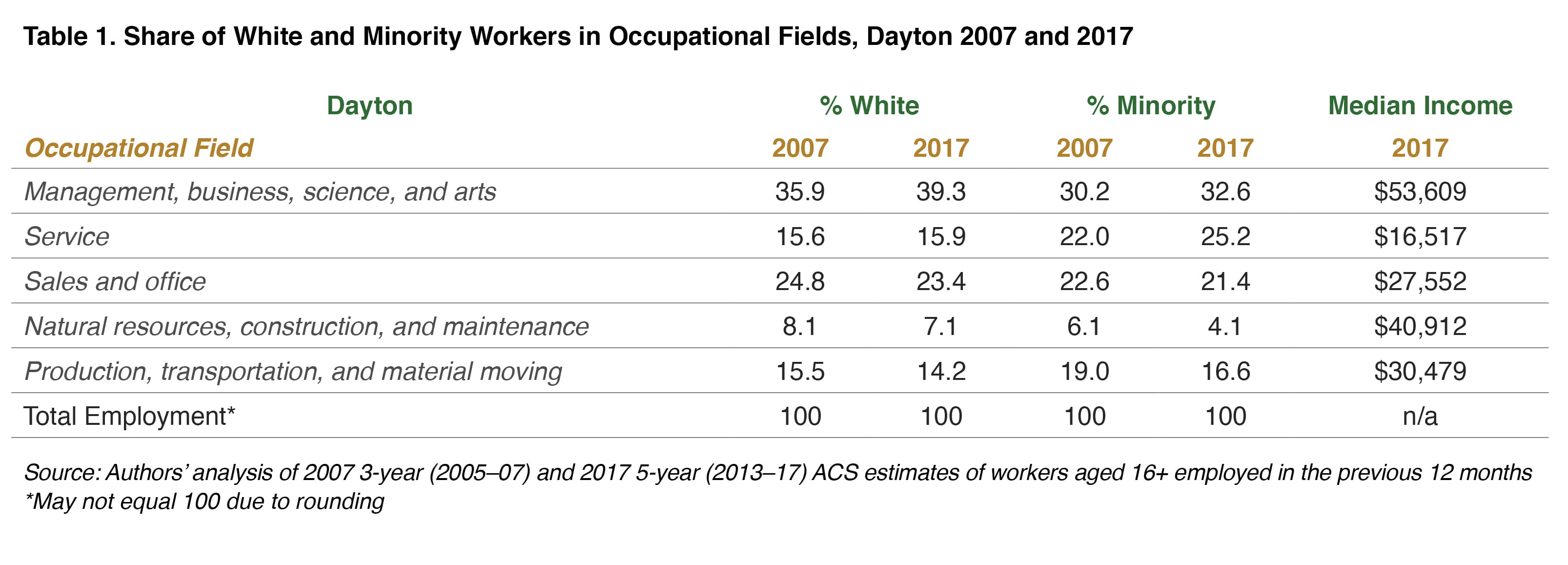

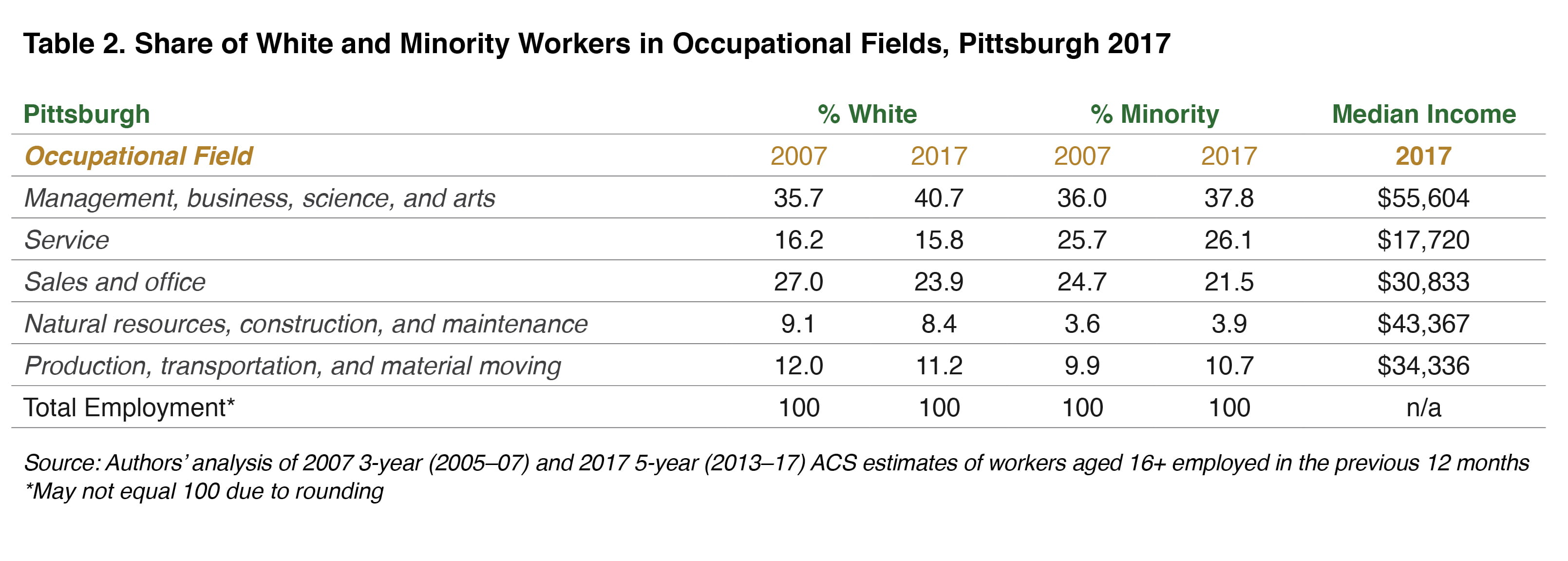

The types of jobs—and who is getting these jobs—matter to the economic mobility of communities. Research finds that disparities in income or wages can be attributed to differences across occupations in which white and minority workers are concentrated.9 The racial distribution across occupations is particularly important when considering one’s ability to earn higher income. We highlight 2017 occupational profiles of Dayton and Pittsburgh to better understand the predominance of white and minority workers in different occupational groupings. We place these trends in the context of other factors affecting local economic development and efforts to promote economic opportunity across all races.

Dayton Metro: Racial earnings gap widens as minority workers’ earnings decline, white workers’ earnings stagnate

Dayton’s story is complex.10 On one hand, it is a story of segregation—particularly between black and white residents—population loss, major plant closures, deteriorating housing stock, and industries that still lag far behind their prerecession employment levels. On the other hand, it is a story of strength, collaboration, and innovation—and the prospect of better days ahead.

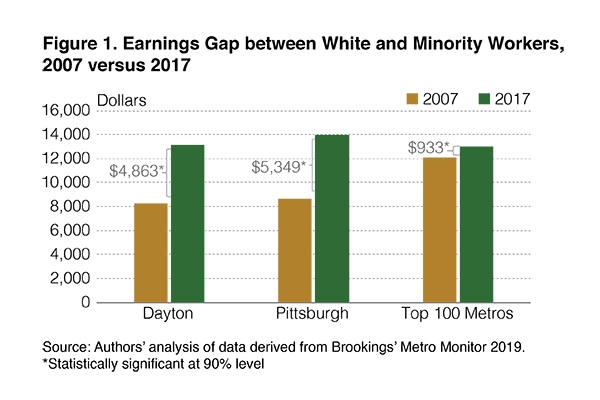

During the recession and recovery, the share of employed working-age minorities grew from 62 percent in 2007 to 68 percent in 2017, helping to close the employment gap between minority and white workers from 11 percentage points in 2007 to 5 percentage points in 2017. However, earnings of minority workers have declined 17 percent in Dayton during the 10-year period (Figure 2), the largest decline among large US metros for which we have data (Appendix Table A). This means that the typical minority worker in Dayton earns less today than in 2007, even when adjusted for inflation. With white median earnings essentially unchanged, the earnings gap increased significantly, from $8,923 to $13,156 between 2007 and 2017 (Figure 1). We see similar trends in metros such as Orlando (Florida), St. Louis (Missouri), and Tampa (Florida): The increase in the racial earnings gap was driven by a decline in minority workers’ earnings.

The loss in earnings for minorities, combined with increased employment, suggests a couple of things about minority workers’ experiences. People who were previously unemployed may have begun working at lower pay or in occupations on the lower end of the pay scale, and minority workers who had been employed consistently during this period may have seen their pay decrease or stagnate or may have had to leave their previous jobs for lower-paying ones.

Looking further into the employment of workers in Dayton in 2007 and 2017, we find that minority workers continue to be disproportionately represented in lower-paying sectors of the economy, particularly in occupations such as food service/preparation, healthcare support, and maintenance. In 2017, 25 percent of minority workers in the Dayton metro area worked in service occupations, which had the lowest median income in the metro area ($16,517, Table 1). This is up from 22 percent in 2007 and is about 9 percentage points higher than for white workers (16 percent) in 2017. In contrast, 39 percent of white workers in 2017 worked in management, business, science, or the arts, occupations which had the highest median income in the metro area ($53,609), compared to 33 percent of minority workers in these occupations. While Dayton’s discrepancy between white workers and black workers in the metro’s highest-paid occupations is not as large as the racial disparity nationally (42 percent versus 29 percent), it is notable.

Even if one isolates the earnings data to the latest five years of the recovery (2012 to 2017), earnings for minority workers in Dayton still decreased by a statistically significant 11 percent. As the recovery continues, community stakeholders must ensure that minorities are provided training resources and employment opportunities in the industries and occupations that are not only growing but also providing good wages. Opportunity occupations that do not require a four-year college degree and still pay above the national median wage are a good starting point.11 Occupations such as registered nursing, licensed practical and vocational nursing, heavy and tractor-trailer truck driving, and maintenance and repair work all represented some of the top opportunity jobs in the Dayton area job market.

Local organizations such as the Jobs Plus Initiative and the Greater Dayton Premier Management have made an effort to provide job readiness and to connect people with resources and employment opportunities.12 Efforts are also underway to address issues that disproportionately impact minority workers’ ability to get to and retain good jobs, such as dependable transportation and childcare.13 As Dayton continues its economic transition, it is imperative to align workforce, economic, and community development initiatives to help minority workers to step up—not step down—the earnings ladder.

Pittsburgh Metro: Racial earnings gap widens as white workers’ earnings increase, minority workers’ earnings stagnate

Pittsburgh is an example of an industrial city that has been able to compete with other metropolitan economies to attract new, technology-led growth industries. The “Steel City” is a leader in the energy, robotics, healthcare, and education sectors and has rebranded itself in the era of the knowledge economy.14 Pittsburgh’s economy is expanding, and employment has picked up after some stagnation in employment between 2012 and 2017.15

Despite the economic momentum the metro is experiencing, the racial earnings gap has increased, driven not by the decline of minority workers’ earnings, as in Dayton, but, rather, by significant growth in white workers’ earnings. We see similar trends in places such as Charleston (South Carolina), New Haven (Connecticut), and Springfield (Massachusetts). Between 2007 and 2017, the median earnings for white workers has increased 13 percent in the Pittsburgh metro area, while median earnings for minority workers have remained essentially unchanged (Figure 2). More-recent 5-year data (2012–2017) show a continued increase in earnings for white workers (4 percent) and a more pronounced decline in earnings for minority workers (14 percent). Such trends illustrate a growing gap in earnings between minority and white workers, from $8,635 in 2007 to $13,984 in 2017 (Figure 1).

While the racial gap in earnings increased between 2007 and 2017, the gap in employment rates between minority and white workers decreased with more minorities working. That said, the change in the employment gap has been modest (12 percentage points to 10 percentage points) and is unlikely to explain the stagnation—and subsequent decline—of minority workers’ earnings (for example, from new entrants to workforce coming in at lower pay). In 2017, Pittsburgh remained a metro area with one of the lowest employment rates for minority workers, with only 65.9 percent of working-age minorities employed.

Occupational differences provide some insight into the disparity of earnings over time, and they offer an explanation for white workers’ higher earnings (Table 2). Notably, minority workers are again disproportionately represented in the lowest-paying occupational fields of the economy—services, with median income of $17,720. The services sector is responsible for 26 percent of minority employment compared to 16 percent of white employment. While service-sector shares have remained largely unchanged, the share of white workers in the highest paying sector—management, business, science, arts (with median income of $55,604)—has grown 5 percentage points, while the share of minority workers in the sector has grown by only 2 percentage points. Such disparate growth may explain part of the trend toward higher earnings among white workers.

With the population of Pittsburgh in decline, and the aging of remaining population, it is in the region’s interest to ensure that all residents have the opportunity to train for and fill higher-pay, in-demand positions. Growing sectors of the economy such as healthcare, construction, and manufacturing mirror many of the opportunity occupations identified for the region: registered nursing, maintenance and repair work, construction labor, carpentering, heavy and tractor-trailer truck driving, automotive technician work, and licensed practical and vocational nursing.16

There is no shortage of efforts that the city of Pittsburgh and broader Pittsburgh region are making to connect minority workers to higher-paid positions and burgeoning industries. For example, as part of the city’s OnePGH Resilience Strategy, Pittsburgh has begun to track equity indicators that report disparities by race, gender, or income across 80 measures of well-being.17 They recently appointed a chief equity officer with responsibilities over various sectors (education, workforce, safety, healthcare, and digital inclusion) to ensure opportunity for all residents. This replaces a more neighborhood-focused approach. Such efforts could be ramped up to the regional level to better understand the broader region’s ability (or inability) to connect people with good jobs both within and outside of city boundaries.18 The broader region also benefits from the Allegheny Conference, a 75-year-old business-led coalition with a refreshed focus on economic vitality, a concept which takes the focus off of “growth for growth’s sake” and emphasizes people and place.19 Efforts such as these could have a profound impact on attracting a diverse workforce and removing barriers to higher-paying employment opportunities—particularly for low-income black, Asian, and Hispanic workers—but efforts need to be responsive to current industry conditions and targeted if they are to help close the racial earnings gap.

Conclusion

Disaggregating data by race and geography is necessary for us to understand if the economic recovery is inclusive or exclusive. From the perspective of minority workers in Dayton and Pittsburgh, the answer tends toward exclusivity. Even though a higher share of minorities are working, this higher share does not seem to lead to income growth for minority workers in the aggregate. Although Dayton and Pittsburgh are in two different places on the spectrum of economic restructuring, minority workers in each metro area have significantly lower earnings than white workers.

Dayton and Pittsburgh are not the only metros struggling with growing earnings gaps by race, and they exemplify different types of racial divides at work across the country—gaps likely tied to skills and occupational opportunities accessible to minority workers. Systemic racial inequality and other barriers to employment such as access to education, transportation, and other support services likely all play a role.

Racial earning gaps in all communities should continue to garner the attention of community leaders and policymakers at all levels. It is too early to tell from available data whether the racial disparities in earnings have continued to grow in places such as Dayton and Pittsburgh, but the most recent 5-year trends have not shown improvement. That said, a number of emerging local efforts are trying to reverse the trend of increasing racial disparities generally. Economic development strategies that identify and acknowledge disparate racial outcomes can more effectively improve the economic mobility of all workers.

References

- See Gould, Elise. 2019. State of Working America Wages 2018. Wage Inequality Marches On—and Is Even Threatening Data Reliability. Economic Policy Institute. February. See also Morath, Eric and Soo Oh. 2019. “As Wages Rise, Black Workers See the Smallest Gains.” Wall Street Journal. April. Return

- See Berube, Alan, Isha Shah, Alec Friedhoff, and Chad Shearer. 2019. Metro Monitor 2019: Inclusion Remains Elusive amid Widespread Metro Growth and Rising Prosperity. Brookings. Minority workers are defined here as Asian, African American, and Hispanic aged 16+ who received earnings in the 12 months prior to the survey year. Median earnings measure the annual wage of persons aged 16+ in the middle of a metropolitan area’s income distribution. Return

- The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland (Cleveland Fed) is the fourth of the 12 Federal Reserve System’s Districts. The Fourth District includes Ohio, western Pennsylvania, eastern Kentucky, and the panhandle of West Virginia (169 counties and approximately 17 million people). Fourth District metro areas included in the Metro Monitor 2019 are Akron, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, Pittsburgh, and Toledo. Return

- See Rothstein, Richard. 2017. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Among others, Rothstein was recently featured in a discussion of income’s role in the wealth gap at Policy Summit 2019. See also Solomon, Danyelle, Connor Maxwell and Abril Castro, 2019. Systemic Inequality and Economic Opportunity. Center for American Progress. Return

- See Aliprantis, Dionissi and Daniel Carroll. 2019. “What is Behind the Persistence of the Racial Wealth Gap?” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. Economic Commentary. 2019–03. Return

- See Morris, Michael, Robert Rich, and Joseph Tracy. 2019. As Wages Rise, Are Black Workers Seeing the Smallest Gains? Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. July. Return

- According to Brookings data used here, between 2007 and 2017 data point to a slightly positive correlation between growth in employment rates and median earnings. The relationship is tighter for white workers (correlation=0.43) than minority workers (correlation=0.23). And in some places, the relationship is negative; that is, more people working is associated with stagnant or lower earnings (again, that relationship is more prevalent among minority workers). Return

- See Morris, Michael, Robert Rich, and Joseph Tracy. 2019. As Wages Rise, Are Black Workers Seeing the Smallest Gains? Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. July. See also Berube, Alan. 2019. Black Household Income Is Rising across the United States. Brookings. October. Berube shows that nationally, black median household income has increased since 2013, and exceeded prerecession levels by 2018. However, for some metros such as Pittsburgh, mostly in the northern part of the United States, the black-white median income gap in particular remained much higher than in other parts of the country even with the increase in the black median household income. Return

- Huffman, Matt L., and Phillip N. Cohen. 2004. “Racial Wage Inequality: Job Segregation and Devaluation across US Labor Markets.” American Journal of Sociology, 109(4), 902–936.

Huffman, Matt L. 2004. "More Pay, More Inequality? The Influence of Average Wage Levels and the Racial Composition of Jobs on the Black–White Wage Gap." Social Science Research, 33(3), 498–520.

Grodsky, Eric, and Devah Pager. 2001. "The Structure of Disadvantage: Individual and Occupational Determinants of the Black-White Wage Gap." American Sociological Review, 66(4), 542–567. Return - Lazette, Michelle. 2018. Unemployment, Vacant Properties, Population Decline: Finding Solutions in Dayton. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. Return

- Nelson, Lisa, Kyle Fee, and Keith Wardrip. 2019. Opportunity Occupations Revisited: Exploring Employment for Sub-Baccalaureate Workers Across Metro Areas Over Time. Federal Reserve Banks of Cleveland and Philadelphia. Return

- Lazette, Michelle. 2018. Unemployment, Vacant Properties, Population Decline: Finding Solutions in Dayton. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. Return

- See Pacetti, Emily. 2018. “Trouble Finding Workers? The Answer May Be Transit: Perspectives from Southwest Ohio.” The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. Notes from the Field. March. Return

- For more information on the Pittsburgh metro area economy see Venkatu, Guhan. 2018. Rust and Renewal: A Pittsburgh Retrospective. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland; and Katz, Bruce and Jeremy Nowak. 2018. “Revaluing Urban Growth: Pittsburgh Case Study” in The New Localism: How Cities Can Thrive in the Age of Populism. Brookings Institution Press. Return

- Teshome, Mekael, and Julianne Dunn. 2019. “Pittsburgh—Employment Steadily Advancing.” The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. Metro Mix. September. Return

- Nelson, Lisa, Kyle Fee, and Keith Wardrip. 2019. Opportunity Occupations Revisited: Exploring Employment for Sub-Baccalaureate Workers Across Metro Areas Over Time. Federal Reserve Banks of Cleveland and Philadelphia. Return

- City of Pittsburgh. 2018. Pittsburgh Equity Indicators: A Baseline Measurement for Enhancing Equity in Pittsburgh. Annual Report. Return

- See Barkley, Brett, Emily Pacetti, and Layisha Bailey. 2018. A Long Ride to Work: Job Access and the Potential Impact of Ride-Hailing in the Pittsburgh Area. The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. Return

- Presentation by Vera Krekanova, Chief Research Officer at the Allegheny Conference on Community Development, at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland on November 7, 2019. Return

Appendix

Suggested Citation

Bailey, Layisha, and Emily Garr Pacetti. 2019. “Strong Recovery for Whom? Trends in Dayton, Ohio, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Exemplify Growing Earnings Gaps between Minority and White Workers Present in Many US Regions.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Community Development Reports.