- Share

Policy Considerations for Improving Ohio’s Housing Markets

Staff report

In this report, we outline some of the main findings from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland’s years of research and outreach with Ohio bankers, community development practitioners, and other market participants. We offer this report as an Ohio-centric companion to the nationally focused housing market report issued by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in January 2012, and we offer it in the same spirit as providing a framework for weighing the pros and cons of programs aimed at stabilizing the housing sector. We hope that our analysis can help inform more effective housing policies for Ohioans.

The views expressed in this report are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Executive Summary

Housing markets across the United States are showing signs of real stability. Prices, new construction, and sales are all improving from their recessionary lows. While this is good news for the economic recovery, the fallout from the housing crisis is still with us. Many communities carry scars from rampant foreclosures and vacant properties. Restoring the health of the housing sector is an effort that continues.

This assessment is especially relevant in Ohio. Some of the state’s older industrial cities are struggling with housing troubles whose roots predate the recent crisis. These weak markets require policies tailored to fit their specific needs.

At the heart of Ohio’s housing woes are two long-running trends: decades of population loss and economic stagnation in many of Ohio’s older industrial cities that have given rise to a supply of housing in excess of local demand, too much of which stands vacant and abandoned; and spillover effects from a foreclosure rate that was elevated long before the recent recession. Together, these developments make Ohio a special case that does not fit neatly into the more familiar boom-bust narrative observed on a national scale.

In this report, we outline some of the main findings from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland’s years of research and outreach with Ohio bankers, community development practitioners, and other market participants.1 We offer this white paper as an Ohio-centric companion to the nationally focused housing market report issued by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in January 20122, and we offer it in the same spirit as providing a framework for weighing the pros and cons of programs aimed at stabilizing the housing sector. We hope that our analysis can help inform more effective housing policies for Ohioans.

Research and outreach conducted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland has pointed to five policy areas that merit careful consideration in Ohio:

- A foreclosure fast-track for vacant and abandoned properties: It takes a long time, an average of one to two years for mortgage loans to go from delinquency through the foreclosure process in Ohio. When a home is vacant and abandoned, efforts to protect homeowners may unintentionally create costs with no corresponding benefits. These “deadweight losses” resulting from a lengthy foreclosure process include legal costs, physical damage to properties, crime, and downward pressure on neighboring property prices. Many states have moved to speed up the mortgage foreclosure process in cases where the owner has abandoned the home.

- Elimination of minimum-bid requirements: Ohio law currently requires minimum bids of at least two-thirds of a foreclosed property’s appraised value at the first auction. Although this may tamp down some unhealthy speculation at foreclosure auctions, it may also price some well-meaning property rehabbers out of the market. There are ways to offset the tradeoff between opening auctions to more investors and inadvertently encouraging unhealthy speculation. Eliminating the minimum-bid requirements could also enhance market efficiency by lowering transaction costs and reducing the amount of time properties sit empty.

- Addressing harmful speculation: In extremely low-value housing markets, some entities engage in “harmful speculation,” or the purchase of distressed property with no intent to invest in improving it or paying property taxes. Two features of Ohio law help this business model to persist: The ability to become the new owner of property through a corporation without being registered to do business in Ohio, thus hampering the ability of code enforcement officials to pursue the owner for violations; and the ability to transfer the property without paying back taxes or correcting code violations. Requiring registration with the Secretary of State and the payment of back taxes or of code violations before low-value properties could transfer to new owners could go a long way toward empowering local governments to tackle this problem, with carefully crafted exemptions preventing undue delays in property transfers.

- Expanded access to land banks: Nonprofit land banks have done significant work since the 2009 legislation that established their missions of acquiring, remediating, and putting into productive use vacant and abandoned properties. Property demolitions by land banks can help reduce oversupply of housing, the underlying cause of widespread vacancy and abandonment.

- Improved data collection and access: Good data helps inform decisions made in the public, private, and nonprofit sectors. Understanding Ohio’s housing markets is especially difficult because of the dearth of standardized, electronically stored data. Data storage practices vary across Ohio counties, and are determined by inertia and budget constraints. With reliable data, policymakers, businesses, and community development practitioners can better identify what works and what doesn’t, allowing them to allocate resources more efficiently. The payoff from a small investment in housing data standardization could be substantial.

We begin this report with a recap of recent trends in Ohio housing markets. We focus on the twin trends of the oversupply of legacy housing relative to demand and a persistently high foreclosure rate. We then highlight the specific complications with the foreclosure process across Ohio counties, including the lengthy period of time that it takes to complete a foreclosure. Finally, we lay out five areas where state-level policy might be especially effective in addressing Ohio’s housing problems.

The Nature of the Problem

Housing markets are struggling in many of Ohio’s older industrial cities. Property values are low, the foreclosure process is lengthy, and some houses stand vacant for extended periods of time. Given that much of the housing stock in central cities and inner-ring suburbs is very old, the combination of these conditions creates an environment conducive to property abandonment and urban blight.

Whether foreclosed, vacant, or abandoned, each type of distress lowers surrounding property values.3 This in turn erodes neighbors’ equity and municipalities’ property-tax bases. Community development practitioners working in Ohio neighborhoods report that vacant and abandoned structures are magnets for crime and vermin, and become fire hazards. Taken together, distressed properties pose serious threats to neighbors, communities, and local governments. Moreover, they inhibit future development of the most affected areas.

The problems of foreclosure, vacancy, abandonment, and low-value property are interrelated. Addressing just one aspect will not make a substantial difference in the overall problem. For example, a large share of the properties that enter the foreclosure process are vacant, and remain vacant during the foreclosure process.4 Ohio’s judicial foreclosure process is lengthy, taking an average of 9.5 months from the foreclosure filing to the sheriff’s sale.1 This process is prolonged even further with additional lengthy periods of loan delinquency (before foreclosure filing) and time spent as real-estate owned (REO) property, during which time the lender attempts to sell the property to an end user.6 On top of that, homes sold at foreclosure auctions, especially in low-income areas, remain vacant at much higher rates than homes sold in arms-length transactions between willing buyers.7

This period of extended vacancy, sometimes beginning even before the foreclosure is filed, provides ample opportunity for homes to fall into substantial disrepair due to lack of maintenance or vandalism (including homes stripped of metal to sell for scrap). The more damaged the home, the less it is worth, and the more likely it will be abandoned. This deterioration likely contributes to the fact that a substantial portion of property sold out of REO sells for only a fraction of its prior estimated market value.8

This pattern foreclosure leading to prolonged vacancy, and sometimes abandonment might seem to suggest that preventing foreclosures is the best way to combat abandonment. But this does not appear to be the case: the majority of vacant and abandoned properties have not been through a recent foreclosure.9 Recognizing that low-value property, foreclosure, vacancy, and abandonment are related but distinct issues, and the macro trends influencing them, is a critical step towards crafting effective policy interventions.

How We Arrived Here

Ohio’s current housing market woes are largely driven by two trends. The first is the supply/demand imbalance in housing markets due to decades of new housing construction that has outpaced household growth. The second is the long-term effect of the elevated foreclosure rate in many of Ohio’s neighborhoods since well before the recent recession.

The Supply/Demand Imbalance in Housing Markets

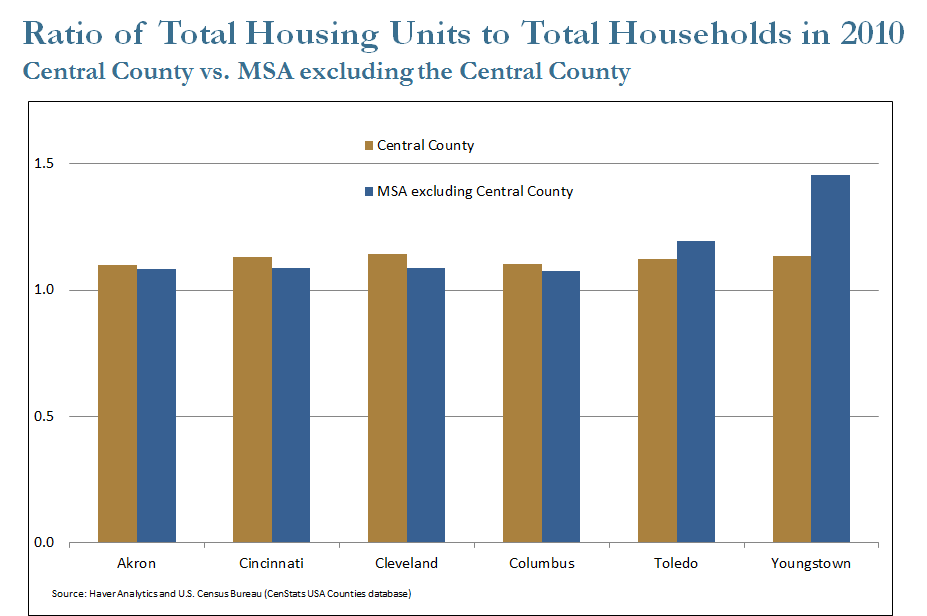

Every one of Ohio’s largest MSAs has more housing units than households to occupy them, a trend almost always exacerbated in the central city.10 The figure below illustrates the ratio of total housing units to total households in 2010. A ratio greater than one means there are more housing units than households to occupy them. Each MSA is divided between its central county (the one containing the central city) and its surrounding counties. In most cases, the central county ratio is higher than the surrounding county ratio because households tend to move ‘up and out’ of the older housing stock in central cities into newer housing stock in suburbs and exurbs.11 In that sense, the excess supply of housing in central cities (and thus their counties) is less likely to be absorbed by future households than the excess supply of housing in surrounding counties is, due to the housing stock being older, and thus closer to the end of its life cycle, and the fact that households are migrating away from central cities.

Ratio of Total Housing Units to Total Households in 2010

Central County vs. MSA excluding the Central County

Source: Haver Analytics and U.S. Census Bureau (CenStats USA Counties database)

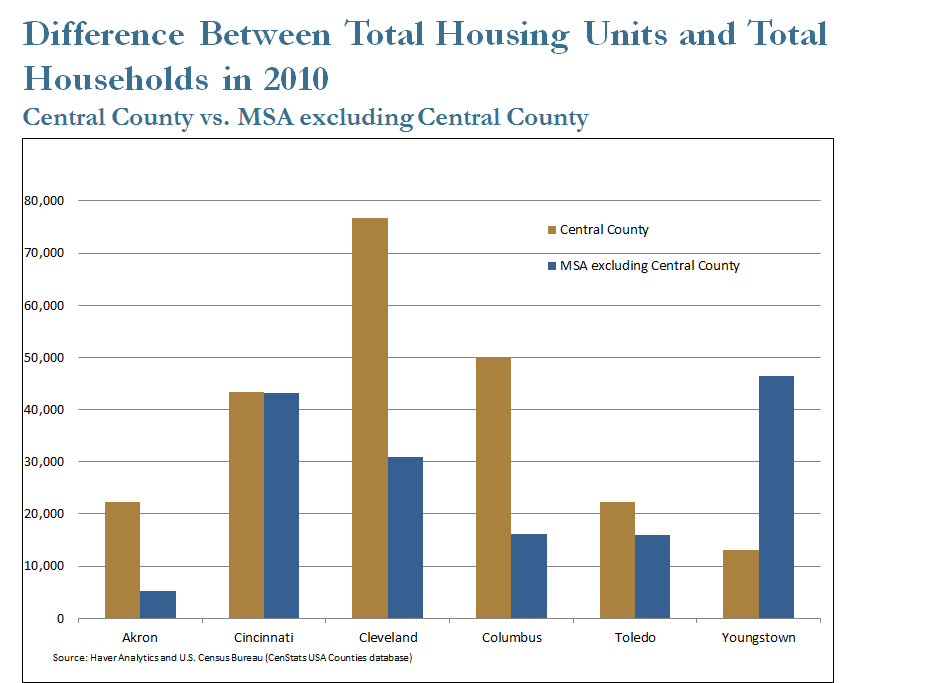

Difference Between Total Housing Units to Total Households in 2010

Central County vs. MSA excluding the Central County

Source: Haver Analytics and U.S. Census Bureau (CenStats USA Counties database)

The ratios are useful for illustrating the trend across counties and MSAs, but the raw numbers give a better sense of the size of the supply/demand imbalance. The above graph illustrates the excess supply of housing units relative to households in the central and surrounding counties of Ohio’s largest MSAs in 2010. It demonstrates, for example, why Cleveland is well known for abandoned property: In 2010 Cuyahoga County, home to the central city of Cleveland, had more than 70,000 more housing units than it had households. It is worth noting that in areas with very large numbers of students not living in dorms, such as Cincinnati (Hamilton County) and Columbus (Franklin County), the estimate of the excess number of housing units to households may be overstated due to the difficulty of counting students. But community development practitioners report problems with vacancy and abandonment, albeit to a lesser extent, in those areas as well.

Change in Housing Units & Households in Ohio, (1980–2010)

| Akron | Cincinnati | Cleveland | Columbus | Toledo | Youngstown | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Building Permits (total units) | 61,976 | 68,828 | 71,264 | 211,864 | 42,090 | 14,746 |

| Total Change in Households | 32,931 | 11,707 | −18,422 | 154,418 | 8,028 | 1,378 |

| Change in Total Housing Units | 44,743 | 34,042 | 25,126 | 179,949 | 17,642 | 3,250 |

| Akron | Cincinnati | Cleveland | Columbus | Toledo | Youngstown | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Building Permits (total units) | 18,570 | 237,696 | 114,603 | 95,057 | 29,991 | 22,173 |

| Total Change in Households | 18,008 | 200,932 | 91,633 | 98,982 | 20,519 | 5,226 |

| Change in Total Housing Units | 19,942 | 224,711 | 106,138 | 107,376 | 24,582 | 12,031 |

Source: Haver Analytics and U.S. Census Bureau (CenStats USA Counties database)

This supply/demand imbalance is the result of a long-running trend. Ohio has long been building more housing units than its households can fill. From 2000 to 2010, 175,000 more housing units were built than households formed in Ohio. The charts above illustrate these trends since 1980 in Ohio’s largest MSAs. In both the central and surrounding counties, more new housing units were constructed than new households formed.

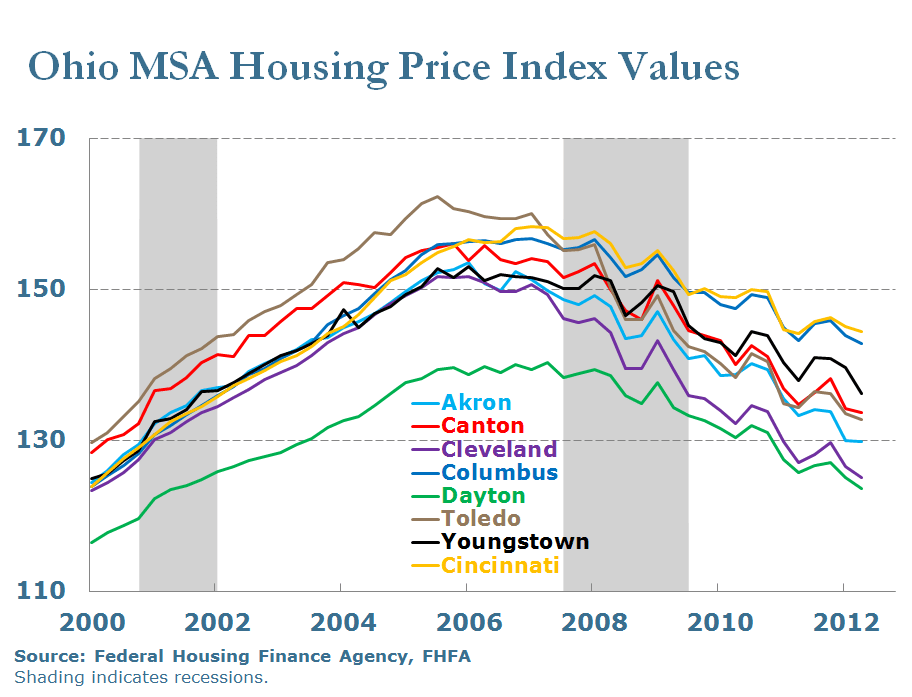

This supply/demand imbalance also helps explain why Ohio’s largest MSAs did not see much housing price appreciation during the pre-recession boom experienced by the nation, but are now experiencing price declines. During the boom, the large availability of housing stock in Ohio put downward pressure on prices, while localized demand and the modest housing price appreciation that was experienced at the MSA level encouraged the construction of new housing in suburban and exurban markets. During the bust, this supply/demand imbalance has continued placing downward pressure on housing prices. Still, the overall price movements at the MSA level during this period were muted relative to national movements.

Ohio MSA Housing Price Index Values

Source: Federal Housing Finance Agency, FHFA

Shading indicates recessions.

Even so, some neighborhoods have experienced quite large price movements. The housing stock in the central city and inner-ring has experienced greater price declines than the MSA-level measure suggests.12 This is partially driven by the steadily growing supply of legacy housing relative to the current population’s demand, which puts downward pressure on prices.13 But the price difference is also driven by unoccupied housing that has fallen into severe disrepair and eventually has been abandoned, often becoming an eyesore that further lowers surrounding property values.14 The differences between housing markets in the central city and some inner-ring suburbs and those in outer-ring suburbs can be seen in much of the housing market research conducted on weak markets: In general, home prices are lower and vacancy rates higher in older industrial central cities than in their suburbs.15

Foreclosure Measurement

Although vacancy and abandonment are caused by aging housing and a supply/demand imbalance in housing markets, recent increases in foreclosures have only compounded these problems. There are many ways to measure foreclosures. Here we focus on two statistics. The first is the foreclosure inventory (sometimes described as the “foreclosure rate”). Foreclosure inventory is a ratio of all of the residential home mortgage loans currently in the foreclosure process (between foreclosure filing and foreclosure auction) to all residential home loans. This tells us the share of loans that is currently in foreclosure. The second measure is the 90-day delinquency rate. This is the share of residential home loans that has missed at least three consecutive payments, but upon which the lender has not yet foreclosed. Once a loan becomes 90 days delinquent, the delinquency is rarely cured (through payment of the arrearage or a loan modification, for example), and these loans tend to transition to foreclosure. Together, these measures give us an idea of not only current foreclosure activity, but probable future activity.

We look at prime mortgages and subprime mortgages separately. We do this to illustrate the issues Ohio was having before and after the recent housing crisis with these different mortgage products. It is important to note that the vast majority of home loans are prime, but the exact ratio of prime loans to subprime loans changes over time. We also only look at 16-30 year amortizing loans, as loans amortizing over less than 15 years are a very small portion of the market from 2000 to 2012.

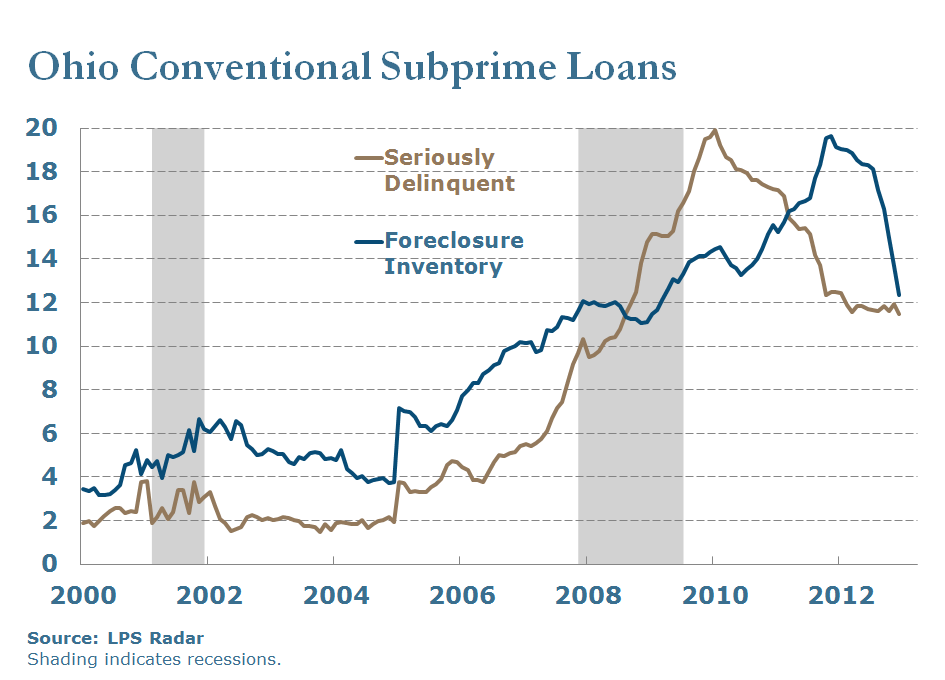

What is clear is that Ohio has been suffering from elevated levels of foreclosure since well before the national housing crisis and subsequent recession, which began in late 2007. Ohio saw an early jump in subprime mortgage foreclosure rates in 2002 (when more than 6 percent were in foreclosure), but these rates did not peak until nearly a decade later (when nearly 20% of subprime loans were in foreclosure). While the subprime foreclosure inventory has dropped from its peak, it still remains uncomfortably high at more than 12 percent. Subprime 90-day delinquency rates also remain high, despite a noticeable drop from their peak in 2010. Beginning in 2006, our data covers a large portion of the market over 80%. According to this sample (which underestimates the total), there were an average of 1,600 subprime loans at least 90 days delinquent and 3,140 subprime loans in foreclosure in any given month in 2006. By 2012, there were an average of 4,200 subprime loans at least 90 days delinquent and 6,160 subprime loans in foreclosure in any given month. Declining rates of 90-day delinquency suggest that lenders are beginning to work through their backlogs, but they remain high, suggesting that subprime loan foreclosures may remain elevated in the coming years.

Ohio Conventional Subprime Loans

Source: LPS Radar

Shading indicates recessions.

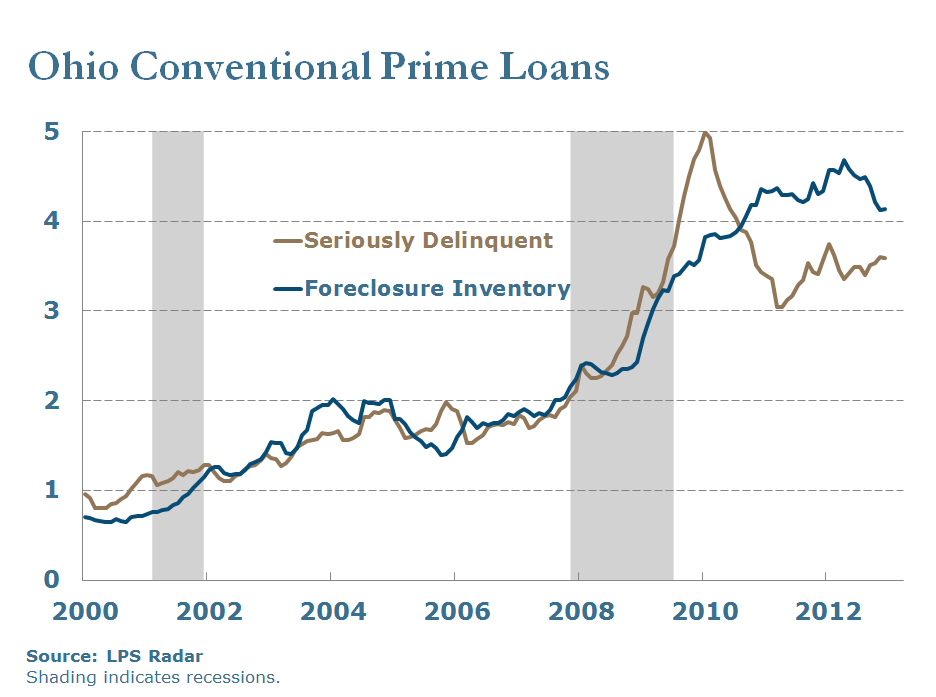

Ohio’s inventory of prime loans in foreclosure peaked in early 2012 at more than 4 percent. Since then the inventory has dipped below 4 percent, but still remains elevated compared to pre-recession levels of less than 1 percent. Using our sample to give an estimate of the magnitude of the problem, beginning in 2006 there were an average of 9,260 conventional prime loans at least 90 days delinquent and more than 9,580 loans in foreclosure in any given month. In 2012, the monthly average had grown to 32,070 conventional prime loans at least 90 days delinquent and more than 40,480 prime loans in foreclosure. Recently, the share of prime loans in 90-day delinquency has increased, although it remains below its 2010 peak. However, it seems to be diverging from foreclosure starts. This strongly suggests that elevated prime foreclosure rates will continue in Ohio for the foreseeable future.

Ohio Conventional Prime Loans

Source: LPS Radar

Shading indicates recessions.

Another factor that may contribute to elevated 90-day delinquency rates is selective foreclosure, where a lender decides not to foreclose on a property because it would cost more to foreclose than could be recovered from the sale of the property. This naturally happens most often when properties are of very low value to begin with. The negative consequence from a decision to not foreclose is that remaining liens inhibit redevelopment by substantially increasing acquisition costs. Compounding the problem is that selectively unforeclosed, low-value properties may be geographically concentrated. Research by the U.S. Government Accountability Office suggests this situation is most prevalent in markets with extremely distressed housing prices, such as Cleveland.16

Our research and outreach suggest that in high-poverty housing submarkets, lenders and servicers are selectively foreclosing on the “best of the worst” properties.17 Before a recent change in law requiring sheriffs to do it, lenders would not always take the steps necessary to become the new owner of record of low-value foreclosed property. This resulted in local governments being unable to identify the actual owner of a property when they needed to contact that owner to address a code violation or property tax bill, for example. There have also been reports of lenders not triggering foreclosure auctions after receiving the foreclosure judgment on a low-value property. In other cases lenders seek to vacate foreclosure judgments rather than take possession of the low-value property. These situations may result in the borrower’s moving out of the home and ceasing maintenance and tax payments, believing ownership has transferred to the lender. Likewise, the lender would not maintain the property or make tax payments, as it is not the owner. Because the economics create an incentive to not take possession of a property, and because there are now many local efforts to force the completion of the foreclosure process once it has started, it makes sense that some lenders would simply not foreclose at all. The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System recently released guidance for lenders who choose to discontinue foreclosure proceedings.18Unfortunately, these practices impact only homes that are already in the foreclosure process, and do not address the problem created by the decision to not foreclose.

In sum, Ohio’s housing markets face some unique challenges, including population loss, low-value legacy housing, selective foreclosure, and spatially concentrated abandonment. Solutions to address these challenges are necessarily different from those in states where the housing boom and bust were more pronounced and where population has increased. In the next section of this report, we walk through five key policy ideas whose impact on Ohio housing markets could be especially beneficial.

Policy Considerations

Ohio’s troubled housing sector is only one component of the state’s overall economy. Additionally, there are national and local forces that operate independently of state policy and have a substantial impact on Ohio’s housing sector.19Nonetheless, there are real short- and long-term gains that can be realized by addressing the issues that face Ohio’s housing markets. The policy actions we focus on in this section fall into two categories: 1) addressing the foreclosure process, and 2) addressing the low-value property problem. We also comment on the importance of quality data in helping to inform the decisions of market participants. To help illustrate how the challenges discussed above and the policy considerations discussed below tie to the path homes take to vacancy and abandonment, please review the figure in Appendix A, titled “Policy Considerations for Improving Ohio’s Housing Market.”

Addressing the Foreclosure Process, Part One: A Foreclosure Fast-track for Vacant and Abandoned Properties

Between 2007 and 2012 in Ohio, the average time it took for a residential home loan to go from an uncured 30-day delinquency through foreclosure auction was between 15.5 and 23.5 months.20 The judicial foreclosure process has its strengths, but speed is not one of them. It takes much longer on average to foreclose on a mortgage in states like Ohio that require judicial foreclosure than in states that do not. This is due to a number of factors, including statutorily prescribed periods (the time the borrower is given to respond to a foreclosure filing, for example), the additional opportunity that borrowers have to challenge the lender’s right to foreclose in court, overburdened court dockets, and the numerous steps in the process that create opportunities for bottlenecks. These factors arguably are counterbalanced by the protection afforded to consumer interests and the greater potential for uncovering illegal foreclosure practices.21

But there are cases when these protections create a cost with no corresponding benefit a deadweight loss. The costs of foreclosing on a vacant and abandoned property are numerous: legal fees associated with the time spent on the judicial foreclosure process, for example; physical damage done to the property by the elements or looters; additional crime; and the damage done to surrounding property values. When the owner’s interest in the property has been abandoned and the property is already vacant, the extra protections offered by judicial foreclosure do not benefit anyone.

The Ohio legislature has already mitigated these deadweight losses in the case of property tax foreclosure. In 2006, Ohio’s General Assembly passed House Bill 294, which allows for an accelerated tax foreclosure when the property is deemed vacant and abandoned.22 This provision has been a boon to municipal efforts to gain control of vacant and abandoned properties and return them to productive use. A fast-track provision for non-tax foreclosures does not yet exist in Ohio. It would help eliminate these deadweight losses.

Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, New Jersey, and Wisconsin have enacted laws that expedite the process for non-tax foreclosures if property is vacant and abandoned.23 Most of these bills and statutes apply only to residential real property. They authorize sale of the property within 35 to 120 days after a court determination that it is vacant and abandoned, substantially shortening the ordinary time periods. Several of the statutes also shorten the statutory redemption period the time after a completed foreclosure during which a borrower may repay the foreclosed debt and retake the property for abandoned property.24 These experiences suggest that a carefully crafted law could significantly reduce the foreclosure timeline for vacant and abandoned homes in Ohio, perhaps by as much as one-half.

It is not easy to define abandonment in a way that expedites foreclosure but does not create an opportunity for abuse. Some states allow one or two circumstances such as overgrown vegetation or boarded-up doors to determine whether a property is officially vacant or abandoned. Other commonly used circumstances include accumulation of trash, disconnection of utilities, absence of window coverings or furnishings, police reports of vandalism, unhinged doors, multiple broken windows, uncorrected violations of housing codes, and a written statement clearly expressing the debtor’s intent to abandon the property. Some states require a single observation of the circumstance, while others require observation over a period of time. Buildings undergoing construction, buildings unoccupied seasonally, and property used in agricultural production are often given exemptions.25 Two of the statutes require clear and convincing evidence of abandonment.26(Pragmatically, this means lenders have to do more to prove abandonment than ordinarily required.)

Another consideration is who can file a motion or petition to expedite the foreclosure process. Current laws fall along a spectrum: Colorado’s statute is more restrictive, limiting those who may request the accelerated process to the holder of a senior lien on a residential mortgage loan.27 Indiana’s law is more expansive, allowing a government official to intervene in foreclosure proceedings to establish abandonment.28 This provision recognizes the impact of abandoned property on its surrounding neighborhood and the larger community.

Speeding up foreclosures raises important due process considerations for homeowners. But in cases of abandonment, a growing number of state legislatures have judged the benefits as outweighing the potential costs. Borrowers who have truly walked away from their homes do not benefit from a long and protracted foreclosure process. Nor do lenders, whose ability to take possession of and sell the property is unnecessarily impeded. Furthermore, the community and market impact of delay is significant. Fast-tracking the foreclosure to transfer property into the hands of a new owner could greatly benefit the lender, community, and market without incremental cost to the borrower. However, it is up to policymakers to determine the best way to respond to these issues in Ohio.

Addressing the Foreclosure Process, Part Two: Elimination of Minimum-Bid Requirements

State law requires that the minimum bid at the first foreclosure auction on a foreclosed property be set at two-thirds of the property’s appraised value. Community development practitioners report that this provision is an effective way to keep harmful speculators (discussed below) out of the market, because it removes the potential for ultra-cheap purchases at auction.

Unfortunately, minimum bids may have the unintended consequence of pricing some helpful property rehabbers out of the market. The median loss taken by purchasers at foreclosure auctions who sell their property the following quarter is 35 percent.29 This makes it more likely that lenders will purchase properties at auction because they need not expend new cash to do so they can simply credit bid, based on the unpaid loan amount they were due. Removing the minimum-bid requirement would open foreclosure auctions to more property investors and helpful rehabilitators, assuming that lenders adjust their bidding strategies.

Provided unhealthy speculation can be prevented, removing the minimum bid requirement would be more efficient than the status quo in two ways: First, it would lower the cost of moving property back into productive hands by eliminating the middle man and associated transaction costs. Instead of the bank buying the property and then selling it to an end-user, the end-user would have a better chance of directly buying the property at auction. Second, the amount of time it takes from foreclosure to reoccupancy by an owner or tenant would be reduced, thus shortening the time property sits vacant in neighborhoods.

The trade-off, as noted, is that eliminating the minimum bid requirements would create opportunities for additional unhealthy speculation. We discuss a policy direction that could more finely screen out speculative purchasers below.

Addressing the Low-Value Property Problem, Part One: Harmful Speculation on Low-Value Property

The abundance of low-value residential property in Ohio’s central cities invites housing speculation. We classify “unhealthy speculators” as those who invest nothing, or as little as possible, in maintaining the properties they purchase and often avoid paying property taxes. This type of speculator exists in markets throughout Ohio, and most local housing and code enforcement officials can provide examples. These speculators often own multiple properties, which they hold either in the hope of future home price appreciation or to rent out to tenants. In either case, the property is rarely maintained, often in violation of building and housing codes, and sometimes property taxes are not paid.

To get a better sense of who the unhealthy speculators are, we broke down purchasers into three categories: 1) large investors (who purchased or sold property 11 or more times in a two year period), 2) small investors (four to 10 times), and 3) individuals (three or fewer times). Lenders and Government Sponsored Enterprises (Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the FHA and VA) were examined separately. Our study encompassed vacancy rates and tax delinquency of properties owned by these different types of purchasers in Cuyahoga County between 2007 and 2009. Looking only at foreclosed homes sold by lenders, we found that homes purchased by large investors remained vacant at more than twice the rate as homes purchased by individuals.30 Large investors were more likely than small investors or individuals to allow their property to become property tax-delinquent after purchase, or to allow the pre-existing property tax delinquency to grow. They were also the least likely to pay past-due property taxes after purchase. And these patterns all become more pronounced with extremely low-value properties (those selling for $10,000 or less).

There is more than one way to address unhealthy speculation. Vigorous housing code enforcement may help, especially when used strategically. The problem with housing code enforcement is that it is a labor-intensive, expensive process. And if investors can sell their properties to another investor, a shell company, or an unsuspecting purchaser before they can be brought to court over the code violation, code enforcement becomes less effective. It appears that some large investors are aware they can sell properties to one another and avoid or delay legal repercussions. Eight out of 10 times, large investors sell low-value, tax-delinquent properties to other large investors, and the property-tax delinquency grows.31Additionally, there are times when it can be impossible to bring owners into court. Sometimes they are not registered to do business in the State of Ohio, nor is the company name they are operating under registered in their alleged state of incorporation.

There are two rather simple ways to address this problem. The first is to require that corporate entities purchasing property at foreclosure sale be registered to do business in the State of Ohio before the property can transfer to them. The Ohio Secretary of State’s website has a searchable database of all registered businesses. Thus, determining whether the potential purchaser is registered in Ohio should not substantially delay the purchase and sale of homes. Although this will not make all unhealthy speculators comply with local codes, it should enable enforcement authorities to know where to find owners who are not maintaining their properties in accordance with the law, thus making local efforts such as code enforcement more effective.

The second change that could more directly address the problem would be a requirement that taxes be paid and the property brought up to code before it could be transferred to a new owner. This ought to provide a powerful incentive for purchasers to properly maintain their homes and pay property taxes. Similar laws already exist in a number of states.32 Interestingly, properties that are purchased with a home loan already have a similar system in place. Lenders want to make sure there will not be any outstanding charges that could become liens that supersede their mortgage, so they make sure any that exist are corrected before they lend against the property.

Crafting this law in a way that has minimal negative unintended consequences is no easy task. Even well-meaning property owners may occasionally fall behind on property tax payments or fail to maintain their homes in accordance with the local housing code.

Fortunately, there are a number of ways negative unintended consequences can be avoided. For example, the law could be crafted in such a way that counties would have to opt-in. That way, the law would only be in effect in counties where harmful speculation was a problem, and counties could wait to adopt it until they have the infrastructure to efficiently check for outstanding code violations or back taxes. A number of exemptions may make sense to facilitate the voluntary transfer of property to entities capable of caring for it, such as Community Improvement Corporations,33 public entities, County Land Reutilization Corporations (land banks),34 and similar entities. It may also make sense to allow transfer when the purchasing party has agreed to pay past-due taxes or make necessary repairs according to a mutually agreeable schedule. An exemption may also make sense when transfers are truly involuntary, such as in cases involving death, divorce, bankruptcy, or foreclosure. Finally, homes purchased with credit already have this requirement in place, and could be exempted.

Addressing the Low-Value Property Problem, Part Two: Expanding Access to Land Banks

Ever since the original enabling legislation passed in 2009, Ohio’s County Land Reutilization Corporations, or modern land banks, are proving to be an effective and efficient tool to address vacant and abandoned properties. Land banks are nonprofit entities formed by county governments with statutorily defined missions to acquire vacant and abandoned housing, remediate it, and put it back into productive use. They operate independently, are overseen by boards of directors composed primarily of public officials, and enjoy a stable revenue stream all of which gives them the flexibility, accountability, and capability to tackle the sometimes enormous problem of vacant and abandoned housing.35

The Cuyahoga County Land Bank, the first of its kind in Ohio, now acquires, on average, more than 100 vacant and abandoned properties a month. Since it acquired its first properties in September 2009, the land bank has acquired more than 2,000 vacant and abandoned properties, facilitated the rehabilitation of nearly 500 properties, and demolished more than 1,000 properties. Though property demolition may sound undesirable, it can be a very effective strategy where a substantial oversupply of housing has led to significant vacancy and abandonment.

Ohio’s original enabling legislation allowed only Cuyahoga County to incorporate a land bank. In 2010 the General Assembly responded to the requests of other communities who wanted access to land banking and altered the population requirement to allow 41 additional counties to create land banks.36 To date 15 counties have established, or are in the process of establishing, modern land banks to address vacancy and abandonment. Many of these counties are much smaller than Cuyahoga County, demonstrating that land banks can be effective tools even when operating on much smaller scales. While not every county in Ohio needs a land bank, removing the population requirement would allow each county access to a tool to combat vacancy and abandonment, which they could use should the need arise.

Data Collection and Standardization

Housing data in Ohio is almost literally all over the map there is no statewide standard, and different counties store data differently. We learned this lesson firsthand when trying to gather data on housing transactions and characteristics, parcel lists, and property tax information in electronic form. Storage practices seem driven by inertia and budget constraints.

This poses a large problem. Without standardized, electronically stored data, it is difficult for market participants to fully evaluate programs and opportunities. Data adds an important dimension to the decision making process by framing an individual’s market experience. This can be seen clearly in Cuyahoga County, where Case Western Reserve University’s Center on Urban Poverty and Community Development maintains a free and publicly accessible social and economic data system.37 The Northeast Ohio Community and Neighborhood Data for Organizing, or NEO CANDO, data system is the product of a longstanding collaboration among nonprofit organizations, foundations, government agencies, and the university. Housed in a single location, NEO CANDO regularly acquires, standardizes, and updates data from federal, state, and local governments, which users can download or access through its website.

The benefit of making this data accessible in an electronic format is that it helps the private, public, and nonprofit sectors understand local market conditions and make business decisions, craft policy, and undertake revitalization efforts. Private enterprise uses NEO CANDO to download clean, electronic local government data to use in their analytics. Local governments and community development practitioners use NEO CANDO in a variety of ways from deciding where to focus revitalization efforts to applying for grants. Researchers also use it to better understand local market conditions in a way that would not otherwise be possible. Much of the data used in the research cited in this paper was accessed through NEO CANDO. Data-driven decision making leads to more efficient allocation of resources, and easily accessible electronic data is a tool that benefits everyone.

A first step toward better data would be to consult with businesses, local governments, housing economists, community development practitioners, and city planners to identify the types of data and storage methods needed to enable more applied housing research. This effort could lead to a template for local governments to follow, and perhaps provide incentives for adopting the template. While this may not result in NEO CANDO-like systems being set up across the state, it will nudge local governments towards providing the standardized, electronic data necessary for market participants to make better-informed decisions.

Conclusion

The housing boom and bust has played out differently throughout the country. Difficulties in dealing with foreclosed, vacant, and abandoned properties have hindered the pace of the economic recovery. The pace of recovery can also be importantly affected by the statutes that pertain to distressed properties within the states. The states have opportunities to alter these frameworks in ways that can enhance public welfare.

With the benefit of research and data analysis, we have identified some opportunities for Ohio to improve its ability to deal with foreclosed, vacant, and abandoned properties. This report has observed that Ohio’s housing troubles are the result of forces that have been at work long before the recent financial crisis and recession. The issues are numerous and interconnected, and can only be addressed through sustained and carefully considered programs.

Understanding the tradeoffs inherent in any policy is a good first step. We hope that this report provides the analysis and information necessary to help continue efforts to restore strength and stability to Ohio’s housing sector.

Appendix

Endnotes

- The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland’s empirical research focuses almost exclusively on Cuyahoga County, home to Cleveland, because it is the only county in Ohio that has consistently made its housing market data readily available. However, after sharing this research through outreach in other cities and counties in Ohio, practitioners have informed us that the conditions in Cuyahoga County mirror housing market conditions in many of Ohio’s counties.

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “The U.S. Housing Market: Current Conditions and Policy Considerations” (Jan. 4, 2012).

- For example, see Stephan Whitaker and Thomas J. Fitzpatrick IV, “The Impact of Vacant, Tax-Delinquent, and Foreclosed Property on Sales Prices of Neighboring Homes,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Working Paper no.11-23r (2011) (noting that foreclosed, vacant, and tax-delinquent properties all have different impacts on surrounding property values).

- Safeguard Properties, the largest field servicer in the country, reports that 25% of homes it inspects when loans are delinquent but not yet in foreclosure have already been vacated by their owners or (in the case of rental properties) tenants.

- According to sample data obtain from Lender Processing Services from 2007-2012 and the Bank’s calculations.

- The average time loans spend in delinquency is between 6 and 14 months, depending on how you measure delinquency. If you start counting from the last time a loan payment is 30 days delinquent (meaning a second payment is missed and it will transition to 60 days delinquent), the average time is six months. If you start counting the first time a loan payment is thirty days delinquent (though many of these become current again), the average is 14 months.

- Stephan Whitaker, “Foreclosure-Related Vacancy Rates,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Economic Commentary No. 2011-12 (2011) (demonstrating that foreclosures in higher-poverty areas, which tend to be in the central city, remain vacant after foreclosure at a much greater rate than foreclosures in lower-poverty areas, which tend to be in the outer-ring suburbs).

- Thomas J. Fitzpatrick IV and Stephan Whitaker, “Overvaluing Residential Properties and the Growing Glut of REO,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Economic Commentary No. 2012-03 (2012); and Claudia Coulton, Michael Schramm, and April Hirsh, “Beyond REO: Property Transfers of Extremely Distressed Prices in Cuyahoga County, 2005-2008,” Case Western Reserve University, Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences, Center on Urban Poverty and Community Development.

- For example, see Stephan Whitaker and Thomas J. Fitzpatrick IV, “The Impact of Vacant, Tax-Delinquent, and Foreclosed Property on Sales Prices of Neighboring Homes,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Working Paper no.11-23r (2011) (noting that the number of vacant and tax-delinquent properties in Cuyahoga County far exceeds the number of recent foreclosures).

- Generally, depopulation tends to happen most rapidly in the urban core. See Kyle Fee and Daniel Hartley, “The Relationship between City Center Density and Urban Growth or Decline,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Working Paper No. 12-13 (2013) (In the Cleveland MSA from 2000 to 2010, for example, population density declined most substantially in the central city, while some suburbs saw increases); and Kyle Fee and Daniel Hartley, “Urban Growth and Decline: The Role of Population Density at the City Core,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Economic Commentary No. 2011-27 (2011).

- Thomas Bier and Charlie Post (2006). “Vacant the City: An Analysis of New Homes v. Household Growth,” in Alan Berube, et al. (ed.) Redefining Urban and Suburban America Washington, D.C. The Brookings Institution.

- Francisca G.-C. Richter and Youngme Seo, “Inter-Regional Home Price Dynamics through the Foreclosure Crisis,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Working Paper No. 11-19 (2011) (finding price declines were steeper in the central city and inner-ring suburbs than area averages); and Thomas J. Fitzpatrick IV and Mary Zenker, “Municipal Finance in the Face of Falling Property Values,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Economic Commentary no. 2011-25 (2011) (finding that in 2010 homes in the central city and inner-ring suburbs of Cuyahoga County (home to Cleveland) sold for 30% to 50% of their tax-assessed values, while homes in Cuyahoga County (containing those areas) sold for 82% of their tax-assessed values).

- Glaeser, Edward L., Matthew E. Kahn, and Jordan Rappaport, “Why Do the Poor Live in Cities? The Role of Public Transportation,” Journal of Urban Economics 63(1): 1-24 (2008).

- Daniel Hartley, “The Effect of Foreclosures on Nearby Housing Prices: Supply or Disamenity?” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Working Paper, no. 10-11R (2010).

- For example, see Francisca G.-C. Richter and Youngme Seo, “Inter-Regional Home Price Dynamics through the Foreclosure Crisis,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Working Paper No. 11-19 (2011); Stephan Whitaker and Thomas J. Fitzpatrick IV, “The Impact of Vacant, Tax-Delinquent, and Foreclosed Property on Sales Prices of Neighboring Homes,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Working Paper No.11-23r, Figure 2, p.39 (2011) (mapping the median home sales price in Cuyahoga County, Ohio); Stephan Whitaker, “Foreclosure-Related Vacancy Rates,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Economic Commentary No. 2011-12 (2011) (demonstrating that foreclosures in higher-poverty areas, which tend to be in the central city, remain vacant after foreclosure at a much greater rate than foreclosures in lower-poverty areas, which tend to be in the outer-ring suburbs); and Thomas J. Fitzpatrick IV and Mary Zenker, “Municipal Finance in the Face of Falling Property Values,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Economic Commentary no. 2011-25 (2011) (noting that housing in outer-ring suburbs tends to hold its value relative to county-estimated taxable market values).

- Government Accountability Office, “Additional Mortgage Servicer Actions Could Help Reduce the Frequency and Impact of Abandoned Foreclosures,” GAO-11-93 (2010), available at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-11-93.

- Stephan Whitaker and Thomas J. Fitzpatrick IV, “The Impact of Vacant, Tax-Delinquent, and Foreclosed Property on Sales Prices of Neighboring Homes,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Working Paper No.11-23r (2011) (Noting the positive coefficient on foreclosures in high-poverty areas).

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Guidance on a Lender’s Decision to Discontinue Foreclosure Proceedings” (July 11, 2012), available at http://www.federalreserve.gov/bankinforeg/srletters/sr1211.pdf.

- For example, local governments utilize code enforcement and foreclosure or vacancy registries to help manage housing blight, and federal subsidies impact local housing construction and demolition activities.

- According to sample data obtained from Lender Processing Services from 2007-2012 and the Bank’s calculations. One of the earliest judicial opinions in the recent crisis identifying unlawful foreclosure practices was in Ohio. In re Foreclosure Cases, 2007 WL 3232430 (N.D. Ohio, Oct. 31, 2007).

- Ohio Rev. Code §323.65 et seq.

- Colo. Rev. Stat. §§ 38-38-901 et seq. (2010); 735 ILCS 5/15-1108, 15-1200.5, 15-1200.7, 15-1219, 15-1504, 15-1504.1, 15-1505, 15-1505.8, and 15-1508 (2013); Ind. Code Ann.. §§ 32-29-7-3 and 32-30-10.6-1 et seq. (2012); Ky. Rev. Stat. § 426.205 (2012); N.J. Stat. § 2A:50-73 (2013); and Wis. Stat. §846.102 (2012).

- Minn. Stat. § 582.032 (2010); N.J Stat. § 2A:50-63 (1995), and Wash. Rev. Code. §61.12.093 (2012).

- Minn. Stat. § 582.032 (2010); N.J. Stat. § 2A:50-73 (2013); and Wash. Rev. Code. § 61.12.095 (1965).

- Colo. Rev. Stat. § 38-38-903(3) (2010) and N.J. Stat. § 2A:50-73 (2013).

- Colo. Rev. Stat. §§ 38-38-902(1)(a) and 38-38-901(2) (2010).

- Ind. Code § 32-30-10.6-3(b) (2012).

- Thomas J. Fitzpatrick IV and Stephan Whitaker, “Overvaluing Residential Properties and the Growing Glut of REO,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Economic Commentary No. 2012-03 (2012).

- 31% of the properties purchased by investors were vacant, while only 15% of the properties purchased by individuals were vacant. O. Emre Ergungor and Thomas J. Fitzpatrick IV, “Slowing Speculation: A Proposal to Lessen Undesirable Housing Transactions,” Forefront Vol. 2 No. 1 (2011).

- O. Emre Ergungor and Thomas J. Fitzpatrick IV, “Slowing Speculation: A Proposal to Lessen Undesirable Housing Transactions,” Forefront Vol. 2 No. 1 (2011).

- For example, Maryland, Minnesota, and South Dakota all have similar laws in place. Md. Code, Real Property §3-104 (2012), Minn. Stat. §272.12 (2008); S.D. Codified Laws §§10-21-37 & 38 (1999).

- Organized under Ohio Revised Code § 1724.01 et seq.

- Created under §5722.01 et seq.

- For a general description of Ohio’s land banks based on the bill creating them (but not accounting for amendments since then) see Thomas J. Fitzpatrick IV, “Understanding Ohio’s Land Bank Legislation,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Policy Discussion Paper No. 25 (2009).

- Current law allows any county with a population of greater than 60,000 according to the most recent decennial census to incorporate a land bank. Ohio Rev. Code § 1724.04 (2010).

- Data is made available via the internet, at http://neocando.case.edu/.