- Share

Workforce Development Challenges in Ohio

The views expressed in this report are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Background

The Cleveland Fed has had a longstanding focus on understanding housing issues that impact low- and moderate-income communities. In recent years, the Community Development departments at each Reserve Bank across the Federal Reserve System have intensified their study of housing markets because of their importance to overall economic recovery. In addition, in recent conversations with community-based organizations, foundations, and state and local government officials, we noted another significant challenge that warranted our attention: an overriding concern about an apparent jobs–skills mismatch. Jobs were going unfilled, even in the context of high unemployment, because an insufficient number of workers had the skills necessary to perform them or were not being trained for them.

Through our outreach, we came to appreciate that economic recovery hinges on investments in human capital, namely education and training, in addition to housing, so in 2013 we set out to learn more about the jobs–skills mismatch and the workforce systems in Ohio and Pennsylvania. We took two approaches, a quantitative one based on research and data analysis, and a qualitative one based on structured conversations with different players in the workforce development field. This report, a summary of our qualitative approach in Ohio to date, is very much an initial foray into untangling Ohio’s workforce system and understanding its challenges. We will use what we’ve learned to design a framework for future study and outreach.

Methodology

Between March and August, 2013, the Cleveland Fed’s Community Development Department met with individuals throughout Ohio who represent many but not all components of the state’s workforce development system, including Workforce Investment Boards, one-stop Workforce Development Centers, community colleges, community-based training providers, intermediary organizations that support particular industries, the Ohio Board of Regents, and the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services (see Appendix A). In order to identify these organizations, we first charted workforce programs and initiatives funded by state and federal programs. We also approached several foundations, a statewide policy-oriented organization, and industry-focused trade and advocacy organizations to fill out our map of the workforce system. We learned of additional organizations and individuals through research and referrals as we progressed.

In our meetings, we asked individuals to help us understand their organization’s role in the workforce system, to share their major concerns about the system, to list their agency’s challenges, and finally, to identify strategies, promising approaches, and how they measured success. Following are the themes that emerged.

Findings - Challenges

Policy. The workforce system in Ohio is fragmented and complex. Many government and private-sector organizations administer different programs geared to different populations and use various streams of state and federal funding. Often based on the requirements of funders, programs can have different time frames and reporting standards; agencies cannot leverage resources from one program to another. In addition to being fragmented, the shape of the current system and how it’s funded was determined by the Workforce Investment Act (WIA) of 1998. WIA, a replacement for the Job Training Partnership Act and other federal programs, created Workforce Investment Boards (WIBs) and directed states to define workforce investment areas. WIA was designed at a time of full employment—a very different era from today’s post-recessionary economy—and its program dollars have historically been attached to individual job seekers, not to employer's needs.

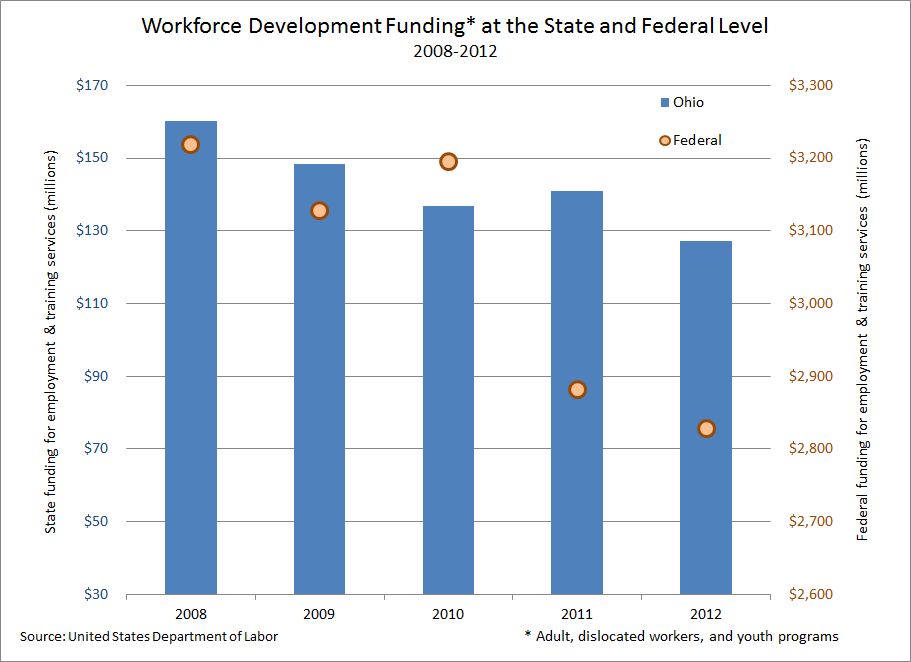

Funding. State and federal funding for workforce development has decreased in recent years, making it difficult for organizations that deliver training and placement services to prepare and place workers for jobs available today while also training workers for employer's future needs; many organizations simply don’t have the resources to do both. We found that many employers have a need for mid-skilled workers who require training short of a college degree, but longer than a year or two. The programmatic emphasis of WIA has been short-term training for quick re-employment. In addition, fewer resources squeeze the system’s capacity to provide supportive services that can help the hard-to-employ and others with employment barriers succeed in the workplace.

Workforce Development Funding* at the State and Federal Level: 2008-2012

Source: United States Department of Labor

* Adult, dislocated workers, and youth programs

Training needs. One community college official told us that “it’s a massive challenge to figure out how to identify talent needs and skills needed.” For instance, educators and employers have different vocabularies for talking about workforce development and skills training. We were told that employers often develop job descriptions that delineate required skills that do not coincide with skills as defined by community colleges. This contributes to an information gap on skills requirements and competencies for middle-skill jobs and makes it difficult for educators to design appropriate curriculum. Compounding this, educators are challenged to find real-time labor market data and analysis that would help them identify current and future employer demand. Thus, educators and economic developers are unable to shape curriculum for in-demand skills enhancement. A related phenomenon is a push-pull between the private and public sectors in taking responsibility for investment in and provision of training.

Pipeline. In many industries, a large proportion of workers—those of the Baby Boom generation—will retire in the next five to 10 years. We were told that, for many reasons, there aren’t enough workers to fill their positions. Many employers would hire mid-skilled workers who have some secondary school credential that is not a college degree; however, today’s educational system is primarily oriented toward students who plan to go to college, in terms of both curriculum and counseling resources, not on job or career readiness.

Employers in certain industries, like manufacturing, struggle to attract youth to jobs. For both parents and students, there is a stigma attached to manufacturing and factory jobs, which are tainted by outdated visions of dirty factories and assembly lines of the past. Most modern factories are in fact clean facilities, and workers need to have relatively sophisticated skill sets to operate their high-tech equipment. We noted concern about a shortage of young people going into the trades, particularly construction, in southeast Ohio.

We would be remiss if we did not report that we were told time and again that some pipeline issues may be due to employer expectations that could be tempered. What employers want in terms of experience and qualifications just does not match the current workforce. One community college official told us that “employers want job candidates who have both experience and specific educational credentials. They tend not to consider whether or not job candidates are trainable.” Many employers are operating in what was referred to as “Great Recession mode. “ That is, when the unemployment rate was high, they could find candidates with college degrees and work experience even for low-skilled jobs, and they often could expect to pay less than market wages. Employers invested less in training new and incumbent workers. However, based on their current need for—and lack of—experienced mid-skilled workers, more employers are beginning once again to provide internal training for new and incumbent workers.

Another pipeline issue is that today’s workforce, especially youth, lacks job readiness. In other words, they do not have the “soft skills” that would help them succeed in any job. Examples of soft skills include reporting to work on time, knowing how to dress for the workplace, and having the interpersonal skills to interact with people and to work on a team. Another major issue for employers is the large and growing number of job applicants who do not pass drug screening tests. This could speak to the prevalence of drug use in our society, but may also be a reflection of increasing numbers of employers screening for more jobs with tests that detect a greater number of drugs. The use of a criminal background as a screening device also eliminates a significant number of job applicants from consideration at the outset, regardless of what skills and work experience they may have.

Information gaps. Given the complexity of the workforce system, it’s not difficult to imagine the problems any job seeker would have in finding out about job opportunities and identifying organizations that provide job training and placement services, or learning about skills that will be needed in the future. It often takes an event—unemployment, displacement, or re-entry, for example—for some workers to connect with some part or parts of the system. Information gaps exist for the workforce system as well: There is little to no standardization of data among workforce agencies. For job seekers, including youth graduating from high school, finding information about job opportunities and possible career paths can be a challenge. Information about jobs is not disseminated in a systematic way. The last places it reaches are high school guidance counseling offices, and even if it gets there, a counselor may or may not be on staff to make use of it.

Hard-to-employ. Lower-skilled workers with barriers are challenged by the lack of supportive services, which they often need to successfully complete training and stay in jobs. Barriers include criminal backgrounds, computer illiteracy, no high school diploma, poor English skills, and dysfunctional family situations. Jobs for those with barriers tend to be entry level without career paths, or even opportunities to improve on basic skills. For many, the cost of obtaining credentials can be an additional barrier, particularly for those who attend community colleges and have other family and work responsibilities.

Findings - Promising Approaches to Workforce Development

Training needs. State and regional industry-sector strategies have the potential to address many employer pipeline concerns and at the same time can afford workers training and employment opportunities that would enable them to progress in a career. Sector strategies are employer-driven and connect employers in certain industries with community colleges to align curriculum with skills required for current jobs and those with projected shortages. Employers help community colleges design curriculum for two-year degrees and industry-recognized credentials.

An intermediary organization that brings all needed parties together to collaborate can help facilitate a sector strategy. For example, Partners for a Competitive Workforce in Cincinnati is a nonprofit intermediary organization that has acted to promote sector strategies in health care, information technology, and manufacturing in southeast Ohio and Northern Kentucky since 2008. It was launched in recognition of the need to coordinate efforts around the skills-gap issue, especially in information technology and manufacturing. Its leadership includes workforce investment boards, key employers, chambers of commerce, and community-based organizations. The organization acts as a convener, facilitator, and fund raiser. An intermediary organization can help identify and braid together funding streams for training programs. But, according to one intermediary director, funding for operational support for such efforts is lacking. More foundations are becoming interested in sector approaches and collaborations, however. Workforce Matters, for example, is a national network of funders interested in learning about and advancing sector strategies.

Sector strategies often work in tandem with “career pathway” strategies, which provide “ladders” that improve workers’ ability to enter and advance in certain industries with ongoing education and training. One example shared with us involved a woman in Cincinnati who began working for a hospital as a nurse’s aide, and eventually worked her way from passing the GED to earning a bachelor’s degree in nursing through an initiative led by Health Careers Collaborative of Greater Cincinnati, an employer-led partnership that focuses on job and educational advancement for low-income adults. This initiative is supported by the Health Careers Pathways Consortium and a Department of Labor grant. The health Careers Pathways Consortium, led by Cincinnati State Technical and Community College, includes nine community college co-grantees and six partner organizations. Consortium colleges partner with local employers and community and workforce agencies to develop competency-based curricula. To date, more than 3,000 participants are being served by the nine co-grantee colleges, with more than 80 programs of study.

In Northeast Ohio, the Regional Information Technology Engagement (RITE) Board takes a sector approach to technology. The RITE Board, like other sector approaches, conducts “job profiling” to determine core competencies for jobs. In developing core competencies, educators and employers create a common language and develop industry-recognized credentials. “Stackable credentials” are those that build on core skills and give workers transferable competencies appropriate for many jobs. The National Career Readiness Certificate (NCRC) represents certain levels of achievement and job readiness; for many workers, it serves as a foundational certificate.

Local demand-driven models have shown some success in placing people in available jobs. For example, a recent Policy Matters Ohio study found that Employment Connections, the one-stop resource center for Cleveland and Cuyahoga County, increased its placement rate as well as the average earnings for workers after shifting its focus to employer needs and matching them with qualified pre-screened candidates.

A word of caution: Early in our discussions, one workforce development consultant warned that, while sector- and employer-driven strategies are promising, not enough research has been done to validate their success. The Cincinnati Health Careers Initiative has an evaluation component, and more studies may be done as this approach gains traction. Another disadvantage of sector strategies, which are resource intensive, is that their scalability and sustainability may be limited. The Business Resource Network in northeast Ohio is a somewhat different, but regionally focused, model that supports employers. The Business Resource Network is a partnership comprising chambers of commerce, economic development and workforce organizations, government agencies, and secondary education institutions. The organization assists businesses in negotiating the systems and services they must tap into if they are to grow; the premise is that new jobs follow growth. The Network initially focused on three counties and recently received a Department of Labor Workforce Innovation Fund grant to expand to 16 counties.

Pipeline. More efforts are being made to engage middle schools to integrate career training with academic curriculum. For example, Max Hayes, a vocational high school in Cleveland, in partnership

with employers and the community and with the vision of the Cleveland Municipal School District’s “Transformation Plan,” recently revamped its curriculum so that vocational classes focus on the skill-set needs of local manufacturers, while maintaining the integrity of academic classes. The school aims to make students job-ready and, at the same time, prepare students to go on to a number of secondary education opportunities, including college.

Early-college high school is another model for addressing training needs and cost barriers. The curriculum blends high school and college courses and enables high school students to earn an associate’s degree before they graduate. There are several such programs in Ohio, including one located on the campus of Lorain County Community College. There is a growing awareness of the importance of experiential learning, and the apprenticeship model, which combines classroom learning with on-the-job training, gives students and workers the experience expected by employers. Often, wages offset the costs of these programs.

Soft skills. A soft-skills gap was a persistent theme in our meetings and discussion with workforce professionals. One agency, El Barrio, the workforce arm of the Center for Families and Children, addresses the soft skills issue through its training programs and supportive services, including its nationally recognized customer-service training for career-ready youth. This is a one-month program that focuses on the banking, retail, hospitality, and call-center industries and leads to certification in health and wellness, customer service skills, and call-center skills. El Barrio’s corporate partners conduct the training, and, while doing so, identify candidates for job openings. While in training, students must adhere to a dress code, and they make visits to corporate sites three times a week.

Hard-to-employ. Policymakers have recently recognized the economic importance of supporting the successful reentry of those who were formerly incarcerated. A 2012 Ohio state law addresses the issue of collateral sanctions by allowing felons to seal the records of one felony and one misdemeanor conviction or two misdemeanor convictions. Additionally, it provides a certificate of qualification that allows ex-offenders to obtain some occupational licenses, including barbering and truck driving. Nonprofit organizations that work on reentry issues are innovating on the training front. For example, the Franklin County Reentry Task Force recently received a $750,000 federal grant to work with the Ohio State Reformatory for Women to operate a job-skills and education program that will lead to certification for inmates trained for home weatherization and energy efficiency jobs. As part of the program, inmates participate in a six-week internship after they are released from prison; during the internship, they are supported with mentoring and housing assistance. In Cleveland, Towards Employment, an agency that provides training and supportive services to workers striving to overcome barriers, received a Social Innovation federal grant to operate WorkAdvance, a sector-focused workforce development program that aims to connect low-wage workers to jobs that have career paths in manufacturing and health care. The program provides ongoing supportive services. Significantly, WorkAdvance has an evaluation component that will produce evidence-based results and could provide a basis for replication of the initiative.

Conclusion

The workforce system in Ohio is indeed complex, and it would be easy to conclude that many of its challenges could be solved with more funding. More funding would help, and some current initiatives seem to be experiencing success in addressing the training needs of employers and talent shortfalls in the pipeline. However, employers and job seekers continue to experience information gaps, and educators still grapple with a lack of real-time market data. The workforce system could be enhanced if data about it were coordinated and standardized, and if information about job opportunities and career pathways were made more accessible to researchers, service providers, and job seekers, particularly youth. Standardization could be a step toward facilitating transfer of information between employers and trainers, and employers and job seekers. One potential tool for this could be the virtual one-stop MONSTER database developed by Ohio Means Jobs. Given the fractured nature of the market participants and differing data sets, Ohio’s executive branch could play a pivotal role by investigating ways that data kept by agencies could achieve some level of standardization. In addition to addressing data gaps, there was agreement among the individuals and groups we spoke with that there is a lack of agreed-upon training standards. If developed, such standards could be used by educators to design curriculum, by employers to clarify needs, and by job seekers to set realistic goals.

What is success? The answer to this question varied by organization and program. Metrics shift depending on goals. Perhaps a standard measure of success could be developed by analyzing how programs or approaches synch with a region’s overall economic development strategy and how they contribute to individual, neighborhood, and regional prosperity. Additional evaluation of employer-driven, industry-focused sector strategies would help inform this issue; such an evaluation should also assess potential for scalability and sustainability, as well as the feasibility of replicating; it should also incorporate some measure of inclusion.

The more intractable problems—increasing the employability of those with barriers and improving soft skills—need thoughtful, innovative approaches. Efforts are being made, but they are small in scale. This could require educating employers on the challenges today’s workforce faces and shifts in attitudes that would allow for increased investment.

Next Steps

Released in tandem with this report is a summary of focus-group-like meetings that were held throughout the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 2013. The Cleveland Fed will continue to analyze data to better understand the labor force challenges in our District. We will stay engaged in outreach efforts, such as convening an advisory group, that will help us understand workforce system challenges and training needs. We hope to show local and regional economic policymakers that addressing human-capital issues contributes to overall community health. To this end, we will continue trying to better understand the funding infrastructure of federal and state workforce systems and training programs, particularly for the hard to employ, in order to better appreciate the challenges faced by service providers and training deliverers, and to better assess the value of proposed legislative changes.

Finally, we have many unanswered questions we look forward to answering, such as

- How disparate are the skills and experience of the current workforce and true employer needs (versus post-recessionary expectations)? Is there actually a jobs-skills mismatch or is it a mismatch of the state of the current workforce and employer preferences? Or is it a gap in soft skills?;

- To what extent are employers training incumbent and new workers “on the job”? How willing are they to provide internships, coop experiences, and apprenticeships? At the end of the day, how do employers take these experiences into account when hiring?;

- What other strategies can employers use to develop the talent of their workforce? How willing are they to experiment with alternative models of supporting employee training (e.g., paying tuition up front rather than after the fact);

- To what extent are employers using certification and credential attainment in hiring decisions?

- How feasible is it for talent development strategies to be integrated with regional economic and transportation plans?;

- How prevalent is the development of use of and development of competencies in certain industries? How are these competencies “stacked” into credentials? Can standardized curriculum be developed around core competencies?

- How can labor market data be compiled and disseminated in accessible ways?;

- What are the long-term outcomes of sector strategies for workers, employers, and regional economies?

- What does it take–or is it possible–to bring sector strategies to scale?

- What are the collateral sanctions and barriers to gaining employment that the re-entry population faces? How can policymakers and employers further address these and the barriers that challenge people with disabilities?

Appendix: Ohio Agencies and Organizations Met With

- Cuyahoga Community College, Cleveland, OH

- El Barrio Workforce Development Center, Cleveland, OH

- Employment Connection (Cleveland–Cuyahoga County Workforce Investment Board), Cleveland, OH

- Entrepreneur Innovation Institute, Lorain Community College, Elyria, OH

- Fund for Our Economic Future, Cleveland, OH

- Greater Cleveland Neighborhood Centers Association, Cleveland, OH

- MAGNET, Cleveland, OH

- Mahoning and Columbiana Training Association, Youngstown, OH

- Ohio Board of Regents, Columbus, OH

- Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, Office of Workforce Development

- Partners for a Competitive Workforce, Cincinnati, OH

- Policy Matters Ohio, Columbus, OH

- Stark County Development Board, Canton, OH

- The Centers for Families and Children, Cleveland, OH

- Towards Employment, Cleveland, OH

- United Labor Agency, Inc., Cleveland, OH

- WIRE-Net, Cleveland, OH