Does the CDFI Fund Help Low-Income Borrowers?

The Treasury Department’s CDFI Fund awards grants to community development financial institutions (CDFIs) that operate in low-income areas. Awards are intended to strengthen the institutions and increase the amount they lend to borrowers in those areas. This analysis of propriety data from the US Treasury shows that when CDFIs receive grant money, they put it to use as additional loans in impoverished and economically weak areas.

Amid the sluggish recovery, there has been a lot of talk about ways to cut government spending. Yet sound government lending and subsidies can have lasting benefits for the economy as a whole for many years to come. Government programs that invest in communities, especially in areas with low-income borrowers, can help spur growth and earn a positive return on their investments.

These returns, however, can be difficult to measure since many programs have “double bottom lines.” In addition to profits, they have a more socially oriented goal, such as improving the economic opportunities for a disadvantaged group or strengthening the economic viability of a community. The effectiveness of a program in influencing these sorts of outcomes is hard to gauge. But the potential benefits of these government programs make their evaluation all the more important.

One such program is the CDFI Fund, which is part of the US Treasury. Established by the Riegle Community Development and Regulatory Improvement Act of 1994, the purpose of the fund is to invest in community development financial institutions (CDFIs) and support financial intermediation in areas with a great need for investment. Most CDFIs are small and localized institutions, and many are mission based, lending to creditworthy low-income borrowers who have a hard time getting a loan from a traditional bank. Increasing financial intermediation and easing credit constraints are ways to help stimulate economic growth, and the law recognized the need to provide financing to financial institutions working with low-income borrowers to support the long-term economic and social viability of low-income communities.

Using proprietary data from the US Treasury, it is possible to measure the impact of the CDFI Fund on the community financial institutions that receive funding and the return on the fund’s investment. By comparing the increase in lending at CDFIs that receive grants to those that apply but were rejected, we can evaluate how effective the program has been. The results of this comparison (see Cortés and Lerner 2013) show that CDFI Fund grants do increase lending; CDFI grants increase lending by 3 percent. For every dollar awarded, 45 cents is loaned out to borrowers in the first year and up to $1.60 is loaned out within three years.

The Fund: What It Is and What It Does

The core program of the CDFI Fund provides funds to qualified lending institutions for technical and financial assistance. Technical assistance awards can be used at the institutions themselves for various purposes, such as offsetting overhead costs or training staff and loan officers. Financial assistance awards are used to fund loans, loan-loss reserves, or capital reserves and can be as high as $2 million. In 2013 the CDFI Fund awarded over $172 million to institutions that work in low-income areas of the country. Since 1994, the Treasury has awarded $1.3 billion to CDFIs.

There are four types of institutions that apply for funding. The first and largest group is loan funds, nondepository institutions whose only aim is lending. In addition to loan funds, there are credit unions, banks, and venture companies. Institutions qualified to receive CDFI funding operate across the country but typically aim to make loans to low-income neighborhoods.

Institutions apply for an award via a standardized process that includes submitting a business plan and plans for the use of the award money. The applications are assessed by three anonymous reviewers and scored. The scores for each reviewer are added together to get the application’s final score. If there are any outstanding issues with the application, some points may be deducted from the final score. At that point the applications are ranked, and the money the CDFI Fund has been allocated for that year is granted to the institutions, starting with the CDFI applicant with the highest score. Money is awarded until it runs out. An applicant with a certain score may receive funding in one year but not in another if the Treasury has been granted less funding for the program. This makes the application process transparent but also difficult to exploit.

In addition to the technical and financial assistance awards, a number of other programs are part of the CDFI Fund. Two of the largest include the New Markets Tax Credit and the Bank Enterprise Award. The New Markets Tax Credit allows for institutions in low-income areas to receive a tax credit for qualified investments in the area. The program aims to attract new capital to low-income areas, and since its creation in 2000 it has distributed nearly 800 awards.

The Bank Enterprise Award program awards funds to qualified institutions that are insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. To qualify for a Bank Enterprise Award, the bank must be lending in an area where at least 30 percent of the population lives at or below the poverty line or where the unemployment rate is 1.5 times the national average. Since the program began in 1994, it has awarded nearly $400 million to over 400 different institutions.

Evaluating the Program

In an effort to help researchers study the effectiveness of the Fund’s core program, the Treasury provided 10 years of data on all the institutions that applied for and received a technical assistance or financial assistance grant. To evaluate the program, loan growth is measured at CDFIs that received grants, CDFIs that applied but did not receive grants, and credit unions that never applied. Comparing loan growth across these credit unions allows us to see if there is an increase in lending at CDFIs that received a grant, or better still, an increase beyond the size of the respective grant. Of the four types of institutions that apply for funding, this analysis focuses only on credit unions. Credit unions make up a large portion of CDFIs and also have to report Call Report data to their regulator. This makes it possible to compare balance sheet items across different types of credit unions.

The Treasury data makes analyzing the program very straightforward since it is possible to identify both institutions that received an award and those that did not. Also, the 10-year sample helps to tease out trends and what one could expect going forward with the program. The CDFI Fund keeps records of the amount awarded and the application scores to further facilitate analysis.

To begin, the probability of an award is calculated, in order to identify which factors play a role in receiving funding. The factors can be at the level of the institution or at the level of the economy where the institution operates.

The factor that matters most at the level of the institution is whether the firm is already lending. This finding is consistent with the aim of the CDFI Fund, which is to grant awards to firms that are operating in needy areas, in effect subsidizing those firms’ operations. Another factor that matters for the application is the rate of delinquent loans on a credit union’s balance sheet. Higher delinquency rates are associated with a lower probability of receiving a grant. The CDFI Fund wants to grant money to institutions that are making loans to low-income but otherwise qualified borrowers.

A high unemployment rate in the area slightly decreases the chance of a grant, while an increase in the median income in the area can increase it. It seems like the Treasury wants to send its funds to areas that it deems will benefit most from the extra capital, areas that may be constrained but primed to grow.

To evaluate the impact of the awards, credit unions are split into three groups: those that receive an award, those that are rejected, and a matched sample that includes credit unions that did not apply for the award but are of similar size and geographical presence to those that applied.

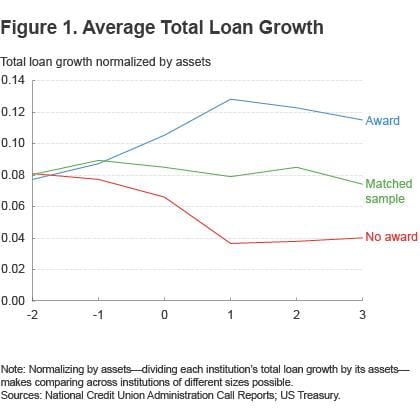

Credit unions that receive awards are generally smaller than the average credit union and less well capitalized overall. Yet average total loan growth increases most at the credit unions that receive an award, while loan growth falls for credit unions that apply for an award but are rejected. Figure 1 shows the growth rates over time for the credit unions in the analysis. The results provide evidence that the CDFI Fund grant has a positive effect on lending.

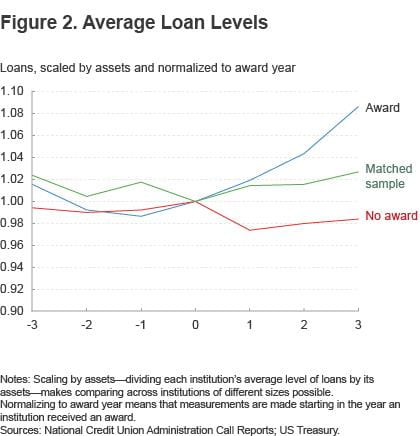

The median size of credit unions that receive an award varies from year to year but on average it ranges from $5 million to $30 million in assets. Figure 2 shows the amount of loans made by credit unions, scaled by assets, and it indicates that credit unions that receive awards lend more over the next few years. The figure compares across credit unions and shows that there is a significant upward trend in lending over a three-year horizon from the award date.

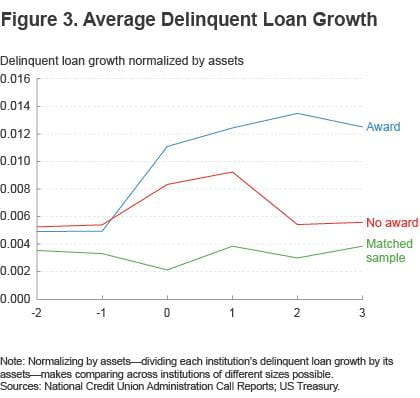

CDFIs lend to borrowers that have a difficult time obtaining a loan from a traditional bank, but the institutions still want to make the best loans possible. That said, they are targeting a population that is much riskier than those targeted by traditional banks, which is why these borrowers get priced out of the market in the first place. Default rates are higher at credit unions that are CDFIs than a matched sample of credit unions that are not CDFIs. Default rates are also higher at the credit unions that receive awards than in the matched sample.

It cannot be determined if the new loans incur the higher default rates, but for every dollar awarded, after three years the delinquent loans increase by 12 cents (figure 3). To give an idea of the size of the increase in defaults, it would be roughly 8 percent of the increase in lending. The average credit union has a default rate at nearly half that at 4 percent. This shows that while credit unions do lend more if they receive an award, by interacting with riskier borrowers, they cannot avoid bad debt.

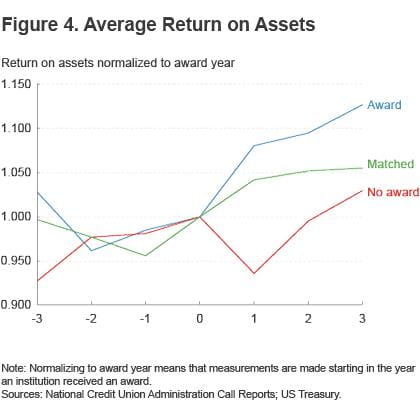

The return on assets for CDFIs that receive awards is higher than both the matched sample and the credit unions that are rejected (figure 4). Additionally, CDFIs’ net worth ratio is positively correlated with receiving an award. This means that CDFI Fund awards go toward recapitalizing credit unions as well. This will allow credit unions to continue to make loans in the future because credit unions require a 7 percent capital-to-asset ratio to be able to expand their loan portfolio. On average, credit unions have capital ratios near 10 to 11 percent, but CDFIs hover around 8 or 9 percent.

While it is informative to compare credit unions that apply for and receive awards to those that are rejected, inherently those are two different groups. This is because the credit unions that were rejected received lower scores on their award application for some reason. This is why it is useful to look at credit unions that have very similar application scores but did not receive funding because the funding ran out in that round. When comparing credit unions around the cutoff for an award one can expect those institutions and their applications to be quite similar. Since the available funding changes each round, it is possible to identify the effects of the award itself.

In this smaller sample of firms near the cut-off, both the increase in lending and the slight increase in the default rates is again apparent. This is evidence that when CDFIs apply for a technical or financial assistance award and receive the grant money, they put the money to use as additional loans in impoverished and economically weak areas.

A Program Worth Continuing

Congress needs to know which programs in the budget have a real impact on the economy. This analysis shows that the CDFI Fund is increasing lending in low-income areas, thus achieving one of the goals Congress set for it. This is, however, only one part of the double bottom line. But since the technical assistance and financial assistance programs are small, it is difficult to tease out their effects on aggregate employment, incomes, or other indicators of the economic viability of the community, which would reflect the other half of the double bottom line.

The core program works well because it is small enough to avoid political capture—politicians can’t divert its funds to preferred private companies—while being direct enough to increase lending in areas that need it the most. Since the CDFI Fund’s mission is to provide credit to a target population, there are stringent guidelines as to which institutions can receive the funds so the grant money cannot be allocated to areas that do not actually need it. It also helps that the program is meant to fund institutions that are voluntarily operating in low-income areas prior to government funding in the first place. The review process is both transparent and anonymous, which helps maintain credibility.

Congress has consistently voted to grant money to the CDFI Fund. Such an investment seems especially important now, as the country continues a slow recovery from a financial crisis plagued by problems in the credit market.

The views authors express in Economic Commentary are theirs and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The series editor is Tasia Hane. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. This paper and its data are subject to revision; please visit clevelandfed.org for updates.

For Further Reading

- Cortés, Kristle and Josh Lerner, 2013. “Bridging the Gap? Government Subsidized Lending and Access to Capital,” Review of Corporate Finance Studies, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 98–128.

Suggested Citation

Cortés, Kristle Romero. 2014. “Does the CDFI Fund Help Low-Income Borrowers?” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary 2014-13. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-ec-201413

This work by Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International

- Share