Operationalizing Inclusion: Tools for Smaller Cities

Smaller cities face some of the same challenges that larger cities do. Here are three tools some smaller cities are employing to promote economic inclusion among their residents.

This entry originally appeared in the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago’s Community Development and Policy Studies Blog. It has been reprinted here in its entirety.

The recent Cleveland Fed Policy Summit focused on “Connecting People and Places to Opportunity.”

This blog summarizes key points made during a panel entitled Inclusive Economic Growth: Tools for Smaller Communities, featuring Alkeyna Aldridge from the city of South Bend, Indiana;1 Alisa Costa from Pittsfield, Massachusetts,2 and Dedrick Asante-Muhammed from the NCRC.3

The discussion demonstrated that some smaller cities are leveraging two characteristics to promote more inclusive economic growth: they are large enough to have challenges similar to those of larger urban centers and small enough to be nimble in developing new solutions. Identifying and benchmarking a robust set of performance indicators to measure a city’s progress, aligning multiple sectors behind widely shared goals, and maintaining a focus on racial economic disparities are among the tools that some cities deploy to promote greater inclusion.

Smaller cities are often portrayed as capacity constrained with restricted resources, panelists spoke of the ease with which community norms and expectations can be adjusted to reflect a practice of culturally appropriate community engagement, for example. According to Ms. Costa, small size also means that resident voices can swiftly be reflected in policy decisions; even small adjustments in community facilities or public spaces can be seen and felt throughout the community; and that the reach of one organization can spread quickly. Aligning residents around a common goal can be more transparent and inclusive in places that, quite simply, have fewer residents to engage. In the case of South Bend, “with 100,000 residents, the city is big enough to have major challenges. But it is small enough to get things done quickly.”

However, small cities are not immune to the conditions faced by larger, urban centers. They contain pockets of concentrated poverty, experience persistent income inequality, and carry legacies of segregation and structural racism, often with few resources to address outcome disparities, which generally manifest along racial lines.

Panelists offered the following insights into how their home cities are implementing practices around economic inclusion, and working to address racial and economic disparities.

Establish key performance indicators (KPIs) – potential indicators include changes in:

- per capita income

- availability of liquid assets (e.g., emergency savings)

- health and sustainability of neighborhood organizations

- number of new neighborhood organizations

- number of residents with neighborhood association membership

- housing stability (e.g., lower eviction rates)

- number of residents assisted

- diversity in hiring, contracting, and spending by city government.

Part of establishing KPIs is setting benchmarks. Ms. Aldridge spoke of South Bend's dashboard of city health indicators,4 which included metrics such as unemployment, access to parks, and childhood poverty, among others (see image 1).

These data points are often difficult to take in, she reflected, but were essential to beginning the journey to rectify them.

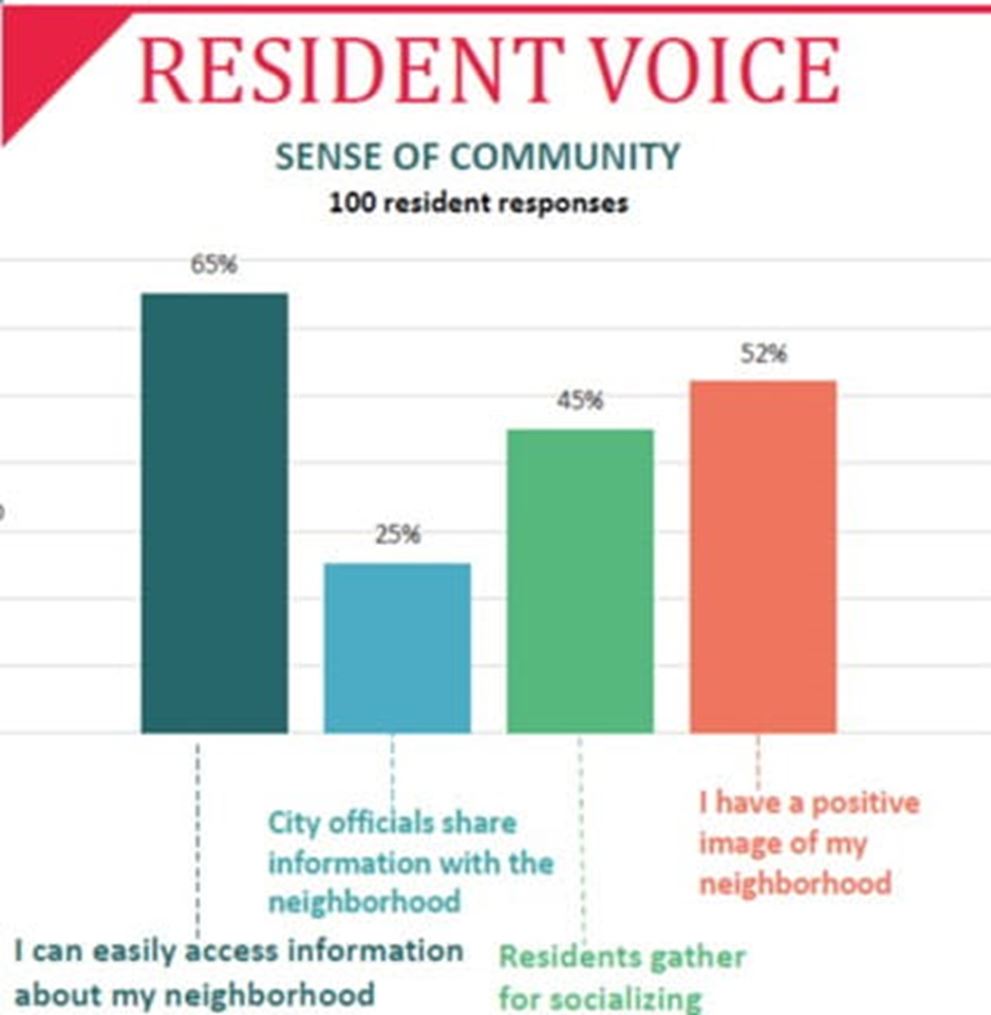

With benchmarks in place, it is easier to align sectors toward common goals. In the case of Pittsfield, MA, using a model of collective impact, resident leaders embarked on a ‘journey from poverty to sustainability’ through community engagement, which included listening to resident voices, valuing different perspectives, and responding with authenticity and respect. Progress is charted through resident sentiment surveys (image 2).

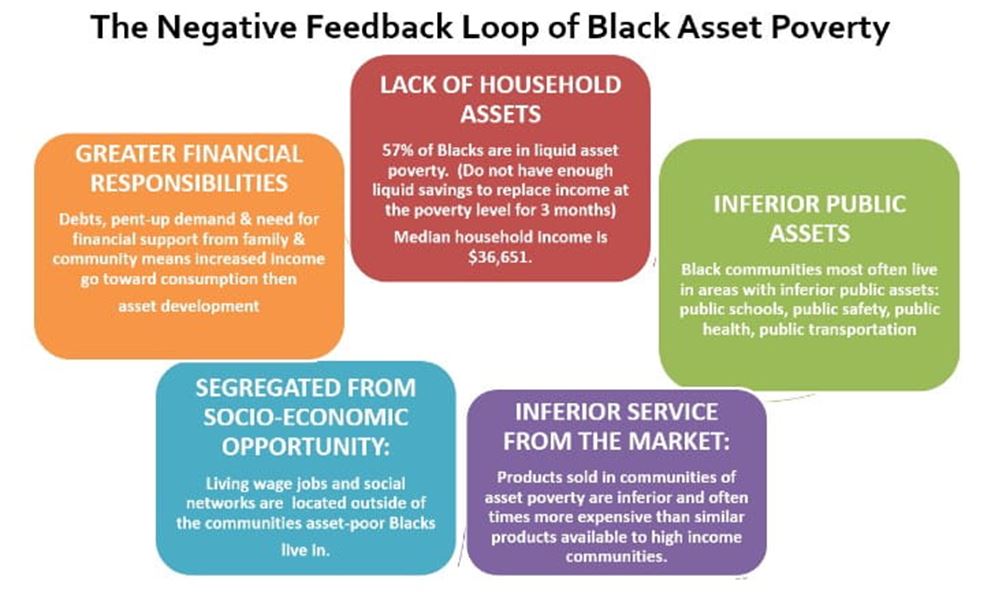

However, as stressed by Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, places – large and small – working to address racial economic disparities will be confronted by what he referred to as the “negative feedback loop of black asset poverty” (image 3).

A vicious cycle of low household assets, inferior public assets, inferior service from the marketplace, isolation from socio-economic opportunity, and the burden of greater personal financial responsibilities challenges local leaders to know how and where to intervene. His solutions for place-based leaders involve six components:

- recognize the racial economic divide

- organize a cohort of institutions of color

- develop a project to engage these institutions for at least a year

- augment understanding about racial economic inequality throughout the community

- use research about racial economic inequality to attract resources

- integrate the goals of addressing racial economic inequality into all facets of community planning and organizing

This panel was motivated by emerging research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, which reported qualitative findings from focus groups on economic inclusion. Preliminary findings are reported here. All presentations from the panel can be found by following this link:

The views expressed in this report are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Footnotes

- Alkeyna Aldridge is director of engagement & economic empowerment in the Department of Community Investment for the city of South Bend, IN. Return to 1

- Alisa Costa is initiative director at Berkshire Bridges Working Cities in Pittsfield, MA. Berkshire Bridges Working Cities is part of the Boston Fed’s Working Cities Challenge. Return to 2

- Dedrick Asante-Muhammad is chief of equity and inclusion at the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. Return to 3

- Indicators are compiled using the NYU Langone Health System’s City Health Dashboard. Return to 4

- Share